Introduction

On a social network site for hip hop interested young people, Sasan, 15 years old, presents his musical production before stating: “I assure you I will make something YOU will like: )”. In what ways does this rhetorical work resemble and differ from the work Sasan does in his school texts? This question is the starting point for the exploration of this boy’s texts, and for the present article.

Research on youths’ literacy practices in and out of school points to large gaps between the two spheres (Andersson & Sofkova-Hashemi, 2016; Bjørgen & Nygren, 2010; Ilomäki, Taalas & Lakkala, 2012), although some studies also point to bridging practices (Gilje, 2010; Karrebæk, 2013). The discussion of both the nature of the gaps and how to bridge them (and whether bridging is desirable), has been part of the field of literacy studies for at least the last forty years, but has got a new turn with the prevalence of digital media in schools and homes.

Reading and analyzing young people’s texts from in and out of school can give a new angle to address this question of gaps and bridges. The present article gives an analysis of two texts by a fifteen year old boy from in and out of school, where the research questions concern how different texts and contexts produce different conditions for expressing oneself, and how a young writer answers to these through his texts. The analysis draws on terms from dialogism and rhetoric. From the dialogic tradition comes the notion of double dialogue, developed by Nystrand and Linell on the basis of Bakhtin, which refers to the way every utterance is always a part of dialogues between speaker/writer and addressee here and now, and with more stable entities, like history and genres (Linell, 2009, s. 52). From rhetoric, Bitzer and Miller’s development of rhetorical situation and exigence as that which invite utterances into being, is drawn on (Bitzer, 1968; Miller, 1984).

The underlying question for the analysis concerns resemblances and differences in texts and writing in and out of school. This is operationalized into three research question guiding the text analysis: RQ1 asks what elements of texts and other speakers have left traces in Sasans texts (a question inspired by dialogism), RQ2 asks how we can proceed from seeing traces in the texts to identify the need(s) rooted in the rhetorical situation for Sasan’s texts to come into being (a question inspired by rhetoric), and finally, RQ3 asks how Sasan’s texts answers to those needs. Implementing the analysis for both school and free time texts, and then comparing them, lets us see differences and similarities in writing in the two life spheres.

Research on young people’s texts and writing across the border between school and life

The urge to better understand young people’s textual utterances in a broader perspective than skills and school, has its background in several related research trends: (1) a growing interest for connections between school and life in fields like pedagogical research and research on young people’s literacy practices (Erstad & Sefton-Green, 2013; Ito et al., 2010; Schultz, Hull, & Higgs, 2016) – which has not yet entirely made its way into research on young people’s texts. (2) Research on writing and students’ texts in school that is founded in a view of writing as not just a competency for school, but also for life (Berge, 2005; Berge, Evensen, & Thygesen, 2016; Christensen, Elf, & Krogh, 2014; Myklebust & Høisæter, 2018). Nevertheless, the perspective in this research has so far been from inside school, and the material is texts and writing in school. (3) A broad anthropological interest for everyday texts and the way they are part of our lives (Barton & Hamilton, 1998; boyd, 2010b; Karlsson, 2006; Karlsson & Nikolaidou, 2016; Ledin, 1997). These last studies are, in spite of theoretical differences, characterized by seeing close relationships between what texts do in different real life settings, and how texts are structured.

Writing research covers studies both of the writing process and of ‘the outcome’, the texts (Nelson & Grote-Garcia, 2010). Karlsson has noted that in studying vernacular literacy, little emphasis is put on the actual texts, as they are often treated as parts of practices, while this is different when it comes to academic writing (2006, p. 28). This implies that there are more studies of young people’s free time literacy practices (Ito et al., 2010; Lüders, 2007; Wernholm, 2018) than studies of texts related to these practices.

Regarding school writing, Berge, Evensen and Thygesen present the model The Wheel of Writing, which draw on literacy research from the last 60 years, in addition to traditions in text and communication theory like dialogism, semiotics and rhetoric (2016). Although developed for a school context, the model attempts to say something about what writing and texts are. They state that,

an instance of writing that is understood as intentional is given the status of an utterance. An utterance is construed as a meaningful act for some more or less explicit purpose in more or less specific contexts […] An act of writing is a meaning-making utterance in a specific situation creating and addressing a model reader and an intentional and/or extensional reference (Berge et al., 2016, pp. 175–176).

In describing texts by young writers this way, they underline that texts by young people (both school texts and other texts) should be read and understood as utterances. This view is partly derived from dialogism (Bakhtin, 1986 [1952–53]), but this view of the (textual or oral) utterance as addressed and as carrying intentionality is also important in rhetoric (Fafner, 1977, p. 44). This common ground between dialogism and rhetoric is also a basis for the analytical work in the present article.

The Wheel of Writing is a typology of different social actions and purposes that textual utterances can accomplish. What is interesting about Berge, Evensen and Thygesen’s model is that purpose is understood as part of the situatedness of textual utterances. However, used as an analytical tool, the six general purposes in the model can be a rather strict framework when applied to actual texts.

A research project with a similar grand ambition, but with its interest placed outside of school, is Kids’ informal learning with digital media by Ito et al. The project establishes the terms friendship-driven and interest-driven genres of participation (2010, pp. 14–18). The daily chat on various social media is typically the friendship-driven, and, for example, blogging about a topic or writing rap songs, is the interest-driven. Although the project’s focus is on practices, several of the substudies are connected to textual genres, like danah boyd’s studies of friendship work in Myspace and Facebook (2010a). The practice-oriented use of the term genre in this project share similarities with both Mikhail M. Bakhtin’s speech genres (1986 [1952–53]) and Carolyn R. Miller’s rhetorical view of genre as social action (1984), which will be outlined in the theory section.

Only a few studies explore young people’s texts in both school and free time, what characterizes them, what actions they are used to accomplish and how they interact with texts and contexts. However, there are some, especially Swedish, studies that explore writing across domain borders and also show an interest in texts (Bellander, 2010; Karlsson, 1997; Svensson, 2014). Bellander’s study is especially interesting. Her aim is to investigate how young people’s use of (oral and written) language varies in relation to different contexts. Her aim is more sociolinguistic than text-oriented, but still relevant in the way she connects and groups linguistic resources, social activities, medium and to a certain extent, written genres to school and free time.

In Norway there are a few studies concerned with youths’ texts that combine ethnographic approaches with text analyses in the broad tradition connected to systemic-functional linguistic, including multimodality analyses: (Gilje, 2010; Michelsen, 2016). Recently, we have seen studies of multilingual literacy practices that have combined an in and out of school perspective and a texts and context perspective, like Dewilde (2017) and Jølbo’s (2016) studies of multilingual youths’ writing and literacy practices. Both Dewilde and Jølbo use socio-semiotic approaches in their text analyses. These studies show the diversity and interconnectedness of persons’ and groups’ texts in different genres, modalities and languages, and the diversity and interconnectedness of persons’ and groups’ literacy practices.

The text theoretical approaches in these studies come primarily from the socio-semiotic tradition. Nordic studies interested in the interplay between texts and various contexts, combined with an in and out of school interest, which apply other text theoretical paradigms, are scarce. It is particularly intriguing that the strong Nordic tradition of studying children’s and youths’ school texts and practices within a Bakhtinian framework (Christensen et al., 2014; Evensen, 1999; Skaftun, Igland, Husebø, Nome, & Nygard, 2018; Smidt, 2010) has not transcended the school walls.

To sum up: There is a room for research concerned with young people’s texts in free time and school, and for discussions on how to understand these texts in relation to various contexts.

Theoretical perspectives and key concepts from dialogism and rhetoric

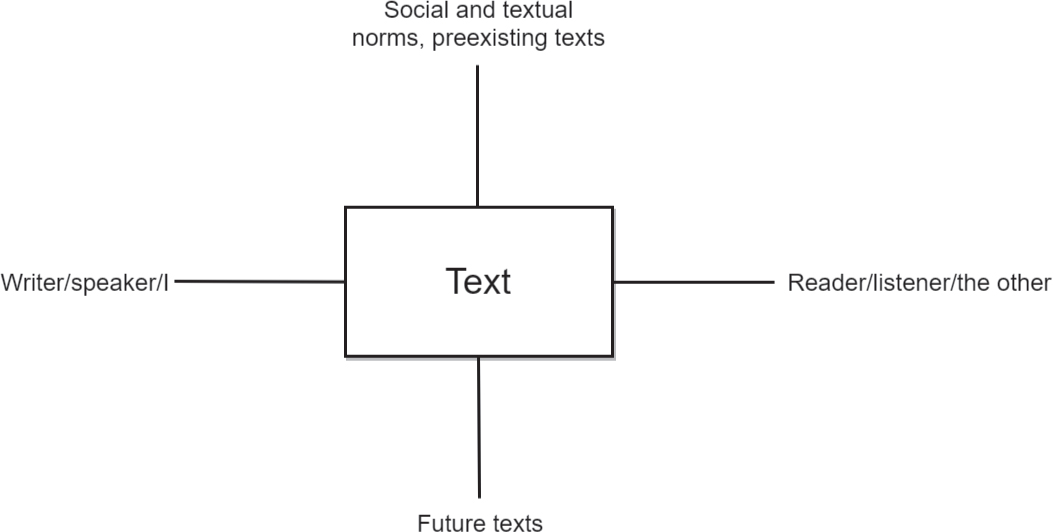

Michail Bakhtin described the utterance and its dialogical relations to both the other parties in direct interaction (Bakhtin, 1986 [1952–53], pp. 68–69) and the reservoir of preceeding utterances in the actual sphere of communication (Bakhtin, 1986 [1952–53], p. 91). These descriptions have laid the foundation for several models of how these dialogical relations work, and for the notion ‘double dialogicity’ (Linell, 2009, pp. 31, 51–53; Nystrand, 1992), which is central to the present article. Double dialogicity refers to the way every utterance simultaneously is part of a dialogue between speaker/writer and addressee (situated interaction) and with larger entities like norms and history (sociocultural praxis) (Linell, 2009, p. 52). This process is visualized in figure 1.

The model in figure 1 builds upon Kristeva’s Bakhtin-reading (1986 [1966]) and a similar model by Evensen (1999), and was developed as a part of the research project Svensk sakprosa (Ajagán-Lester, Ledin, & Rahm, 2003). Ajagán-Lester, Rahm and Ledin, whose interest are texts, name the axes interaction and convention axis, while, Linell, more interested in talk, names the equivalent dimensions situated interaction and situation transcending practices, traditions and resources (Linell, 2009, p. 51). In the following, I will use Linell’s terms; however, Ajagán-Lester, Rahm and Ledin’s highlighting of the textual and stabilizing aspects of situation-transcending practices, like social and textual norms, will be an important part of my understanding of what the situation-transcending material relevant for the analyzed texts, consists of.

The concept intertextuality is a part of the dialogic tradition, as it stems from Kristeva’s reading of Bakhtin (Kristeva, 1986 [1966]). She describes the word as an “intersection of textual surfaces and as a dialogue among several writings” (Kristeva, 1986 [1966], pp. 36–37). On the basis of this, Fairclough and also Ajagán-Lester, Rahm and Ledin ‘translate’ intertextuality into covering both direct traces of other texts, voices and utterances in the utterance (manifest intertextuality), and traces of discourses and genres (interdiscursivity) (Ajagán-Lester et al., 2003; Fairclough, 1992). In the present article, intertextuality covers all of this, while intertextual practices mean ways of using this feature (intertextuality).

When it comes to rhetoric, Miller and Shepherd’s study of blogging as social action (2004) is especially interesting, because it shows how Miller’s understanding of genre as social action (that integrates well with the Bakhtinian concept of genre (see Villadsen, 2001)) applies to youths’ free time practices such as blogging, and argues that blogging should be understood as a genre. Miller and Shepherd build upon Miller’s development of genre as rooted in the rhetorical situation. Although an understanding of the situational basis of speech has been a part of rhetoric with the concept Kairos ever since the sophist Gorgias (Andersen, 1995, p. 22), Lloyd Bitzer created new interest in the concept by stating that answering to a rhetorical situation is what makes discourse rhetorical. To him, a rhetorical situation is a situation that demands an answer (Bitzer, 1968, p. 6). According to Bitzer, there are three constituents of any rhetorical situation: exigence, audience and constraints, of which exigence is the most central. He describes exigence as “an imperfection marked by urgency, […] a defect, an obstacle, something waiting to be done, a thing which is other than it should be” (1968, p. 6). Both the ontological status of the situation and the strength of the demand have been problematized (Miller, 1984; Vatz, 1973). Miller describes exigence as “a form of social knowledge […] an objectified social need” (1984, p. 157). Still, a situation that demands or invites an answer, describes something that is both recognizable for people in communication and for researchers.

In the present article, double dialogue and rhetorical situation are applied as complementary perspectives for understanding the interplay between texts and contexts, and both will be drawn on in the analyses.

A question that a model of dialogic relations between utterances and context also needs to answer is how to talk about expected reading. This is a phenomenon known to dialogism (see Bakhtin, 1986 [1952–53], p. 69), but perhaps explored in more detail by Eco and followers with the concept model reader, described as follows: “The author has thus to foresee a model of the possible reader (hereafter Model Reader) supposedly able to deal interpretatively with the expressions in the same way as the author deals generatively with them” (Eco, 1981, p. 7). Although Eco in this quote to a certain extent places the model reader in the author’s mind, he also underlines that the model reader is a text strategy, and that the model reader is located in the text (1981, p. 7). Ajagan-Lester, Rahm and Ledin have a south pole in their model (see figure 1) called “future texts”. I interpret textual traces of model readers and model readings as part of an inherent future dimension in the text.

Methods

In this section I present the methods used for data collection and analysis in the project in which these texts were collected, and in the present study.

Data collection and data analysis

The two texts analysed in this article were collected as part of a PhD project. The material of the PhD project consists of texts from school and free time from 11 14–15-year old students in grade 9 (lower secondary school), in addition to interviews with the students, partly participant observation and interviews with their teacher. Texts from the students’ free time were blogs, texts from social network site profiles, Facebook threads, rap lyrics, ‘mock blog’. School texts ranged from Norwegian written composition to social science tests, interdisciplinary project work and different science texts. The data were collected between 2008 and 2011. The material is thus a mix of the participants’ own texts, observation and interviews, typical of text ethnographical approaches (Barton & Hamilton, 1998, p. 59; Dyson, 2016; Karlsson, 2006).

The participants were recruited through four schools with different socio-economic and -cultural characteristics. The 11 students were the ones who agreed to participate at each school. The project was approved by the Norwegian Data Protection Services Ombudsman for Research Practice, and follow their guidelines for non-disclosure (Personvernombudet for forskning). The informants themselves picked out a minimum of two texts from school and two from their free time that they allowed me to use, from texts they had already written. All the texts in the material are thus authentic in the sense that my presence did not affect the production of them.

Data selection and analysis in the present study

In the present study I have selected the material related to Sasan to explore more thoroughly the possibilities in a combined dialogical-rhetorical analysis. At the foreground are two texts written by Sasan (one in school and one in free time), which will be presented below and then analysed. In the background (used as supplementary data) are interviews with Sasan and his teacher, field notes from a week of partly participant observation in his class, and also other texts by Sasan: two rap lyrics and the school texts “Fysiske egenskaper til metaller” and “English Literature Project”, his textbook in Norwegian and handouts from class. This was collected during 2010.

The two texts analysed here were selected because they share textual similarities and may highlight certain aspects – the meeting points in the texts between text and world, and to where one assigns the different traces of context in the texts and on what grounds. This is relevant for a discussion of meeting points between double dialogue and rhetorical situation.

In the analysis, I will first do a reading based on the double dialogue model (following (Ajagán-Lester et al., 2003; ; Linell, 2009)), based on RQ1. Afterwards I will do a reading that includes RQ2 that concerns exigence and rhetorical situation. I will do this two-step analysis both for the free time text and the school text, and as we shall see, the answers to the questions are not exactly the same for the two texts.

Informant and texts

Sasan is a fifteen-year-old boy living in an urban area characterized by low and medium income and cultural diversity, which is also apparent at his school. Sasan reveals in an interview that he likes to write, and that he writes a lot. He runs a blog together with a friend, he writes rap lyrics, he writes stuff on different hip hop sites and some things he just writes for himself and saves for later. He also talks of himself as a rapper, as we shall see in the texts. Sasan says he prefers to write in English and Spanish rather than Norwegian. The selected texts are (1) a self-presentation of himself as a rapper on a social networking site for hip hop interested people in the Nordic countries, and (2) a school assignment, a job application for a local grocery store.

Analysis

Social networking site profile page: Biografi in double dialogue

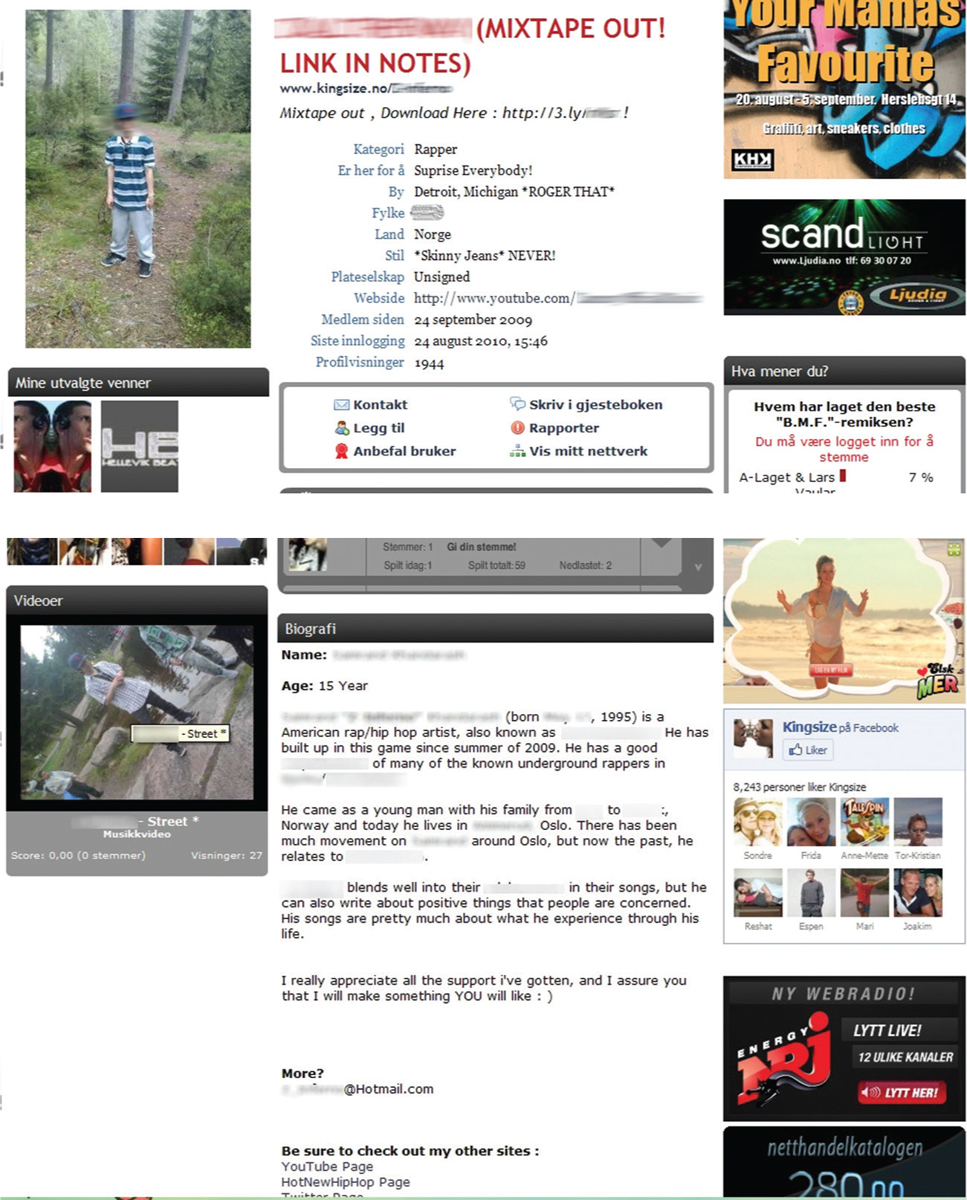

The main focus of the analysis is the part of the page called Biografi (“Biography”) (see text 1).

Already from the first sentence, where Sasan starts by describing himself as “a American rap/hip hop artist”, we learn that Biografi is not a personal biography, it is a musician’s biography. The first paragraph tells us who Sasan is as a musician. The second paragraph describes his personal story, though. The third paragraph seems to be a description of the music, and the fourth a message to his fans. This biography seems to mimic the traditional record company promo text description of a band or a star, which then must be understood as an important preexisting text or a strong textual norm. These are stable features which Linell characterizes as situation-transcending (2009, p. 52), and which we assign to the vertical axis of the double dialogue.

The screenshot also shows some of the other texts and text fragments that Biografi dialogically relates to. Some of the elements on the left hand side of the page can be seen as extensions of Biografi, for example, the profile photo and the video showing Sasan rapping one of his songs, and the music player where you can hear him rap a couple of his songs. These extensions can be seen as examples or ‘proofs’ of what is being described in running text. Other elements are best understood as preexisting texts, for example, the form to be filled out on the upper half of the page and the various commercials on the page. Other situation transcending resources for this text are norms for self-presentations on social networking sites merged with norms for self-promotion through self-presentation in hip hop as genre and culture.

By adopting the record company promo text form in his biography, Sasan chooses an expected reading of his biography as an artist’s biography, and thus prescribes the options for answering. Yet there are elements in the text that challenge this expected reading. Some are in the extended text, as the proofs of Sasan’s rapping and song writing show a novice more than an established artist. Also the final greeting “I assure you that I will make something YOU will like :-)” somehow invites another answer than what the more distanced biography genre does. In the extended text Sasan also asks for feedback: “My mixtape is available to download […] Give feedback about what U think about the mixtape, I Appreciate Good & Bad Comments, Anything”.

In the final part and greeting of the biography text, and by publishing proofs of his production, Sasan invites readers to judge his productions to help him improve, which is another kind of answering act than to admire an established artist. We have thus identified two possible model readers: the fan and the peers/fellow hip hoppers. Johan Tønnesson argues that we must account for the possibility of several model readers in one text (2007). A third might be ‘the agent looking for talents’. In my interviews with Sasan he revealed a hope that someone might discover him and that is why he wrote in English, which has led me to look for this model reader in the text. Both the presentation in Biografi and the samples of his rapping might address such a model reader.

However, the readers of this text are not just model readers. Some of the actual readers are Sasan’s friends, some are more skilled rappers that he seeks (and gets) feedback from, some are just other young people interested in hip hop. When talking about actual readers, we have moved towards the horizontal axis of the double dialogue (also called interaction axis, see figure 1). This axis describes the situated interaction between writer and reader, and the way both reader and writer contribute to create and influence the utterance.

Sasan needs to be nice to his (real) friends despite hip hop clichees about boasting and dissing. He needs to be humble and show respect to the more skilled rappers who can help him develop. Here we have identified a need that can be helped out by discourse, and this points to rhetorical situation. This required humbleness contrasts somewhat with his stated ambition of ‘being discovered’ and the dream of stardom, which can also be described in terms of a need, and thus also points to a rhetorical situation. This will be explored in the next section.

Integrating the perspective of the rhetorical situation in the reading

In these last paragraphs concerning the interaction axis, we have moved from a mainly dialogical understanding to a reading that also includes motivational aspects: We have moved towards the rhetorical concept of exigence, which Bitzer describes as a lack or a need and Miller on occasion, expectation, but also a social need (Bitzer, 1968, p. 6; Miller, 1984, pp. 157–158). Both agree that this is the nucleus of the rhetorical situation.

The most important feature of the notion of rhetorical situation is perhaps its exploration of the configurations of different aspects that together create a need for a text, and its conceptualization of these aspects as demands and invitations from the situation (Bitzer, 1968; Miller, 1984). In doing this exploration, asking what demands and invitations led to this text, we are free to look for answers both in the utterance itself, in preexisting texts, in genre norms and motives that we know from the paths of culture we share with Sasan, and in our knowledge of the utterer’s individual hopes and needs.

As showed earlier, the text seems to imitate the record company promo text. It is possible to read the different paragraphs in the text not just as traces of the record company promo text (see last section), but also as answers to questions dropped by an (imagined) crowd of fans: Paragraph 1 answers to “Who is this artist?” Paragraph 2 answers to “what is your story”/“where do you come from?” and so on. Since the questions are not already present in the text; Sasan is in a way creating them (from resources he has at hand) by answering them, and through this process, defining a rhetorical situation where he is a hip hop artist promoting himself. We can trace this exigence of the need for promotion both to inherent dynamics in artist and record company practices, and to the amateur musician promoting himself while dreaming of being discovered.

Although the need for promotion is an exigence that unites the music industry and Sasan’s dream of stardom, we can trace it to different places, and there is an inherent dynamic between them. Sasan’s need for promotion is tied to the dream of being an artist, but exists also as an extension of his everyday practices of writing. The music industry’s need for promotion is more directly connected to economic motives. We can describe the dynamic between these exigencies in the text as Sasan’s promo text’s imitating the record company promo text and thus ‘claiming’ the promo text’s exigencies. This helps Sasan answer to a ‘need’ that he (and many other young people) have of becoming a hip hop artist.

To discover the origins of the rhetorical need “I want to be a hip hop artist”, we would have to look into the configuration of situation-transcending and situated forces, for example, hip hop as an important cultural expression and identity choice for young people in Oslo. It is also important in the way that hip hop skills give social status (Brunstad, Røyneland, & Opsahl, 2010), combined with a widespread dream of being discovered and of stardom itself. Sasan also reveals more personal exigencies that can be connected to being a rap artist: He likes to write and he writes a lot, e.g. to take care of memories. To write your life can be seen a way of practicing the ideal of authenticity in hip hop (Neal, 2004), and being a rapper might seem a way of doing this on a professional level. To try to be a hip hop artist is thus a way of making oneself heard by answering to demands of what is considered valuable in the local youth culture by using resources from free time practices that he already masters and finds meaningful.

The school assignment: Job application

Writing a ‘job application’ is part of what Norwegian students normally do in lower secondary school, and the assignment is part of most of the textbooks in Norwegian. This is Sasan’s version (translated from Norwegian):

The application (text 2)

Sasan [Surname]

[Address]

[postal code]

ICA

[Address]

[postal code]

05.01.10

APPLICATION FOR PART TIME JOB AT ICA

I received this advertisement from my school on 04.01.10, and I hereby apply for the vacant job.

I am fourteen years old and go to [school name] school. I am in 9th grade. I have not yet taken my exam.

I have worked at a carwash one day through the OD program. I have also applied for a job at [name] activity center, and been accepted. I am going to work at [name] activity center for a whole week (school assignment).

I believe I am suitable for this job because I like to talk to people, and I like work where I have to carry things. I always listen to what people tell me, and I’m always in a good mood when needed.

As a reference, contact [first name, last name], the daily teacher at [school name] school, tel: [phone number].

Kind regards

Sasan [last name]

2 attachments

To uncover the dialogues this text takes part in, the first step might be to open Sasan’s textbook (Blichfeldt, Heggem, & Larsen, 2006). The elements of Sasan’s application follow the textbook’s template, where the steps in the application can be described as follows:

- State that you apply for the job.

- Presentation of gender, age, school, etc.

- Presentation of work experience.

- Presentation of personal skills/why you match the job description.

- References.

Sasan follows the template to such an extent that he has replaced manager (direct translation ‘daily manager’) with ‘daily teacher’, a concept that does not exist in Norwegian.

However, the application also has traces of other textual and social realities: It is addressed to the local grocery store. The listing of his teacher as reference is a trace of the school environment. We also know that this text is part of school’s recurring assignment dialogue: learning/reading in the textbook about a subject, getting an assignment, writing your text, handing it in, getting marks or comments from the teacher.

If we apply rhetorical situation to the reading, we start by asking what the situation demanded or invited this text to drop into the world. Of course we already know the most obvious answer: The teacher asked for this text. The exigence underlying this text is not Sasan’s need for a job, it is school’s explicit request. This application was never sent to the local grocery store. Then the rhetorical need this text has to fill is connected to doing your job as a student, by writing and handing in the required texts, rather than the needs explicitly addressed in the application.

How are we then, to understand the text’s explicit application for a job? My proposal has two elements: First, to see the assignment specification ‘write a job application’ as one of the constraints that narrows down the possibilities in the rhetorical situation of doing Norwegian written composition. Second, to consider the ability to presuppose a fictive, embedded rhetorical situation that the text addresses as a necessary part of giving a good answer to the ‘real’ or main rhetorical situation of writing an assignment. I believe this rhetorical view gives us a better grasp of what is at stake in and around such a text than does a dialogic view alone.

Summing up and concluding the analysis according to the research questions

As asked for in research question 1, in these two texts we have seen traces of clear textual templates, the record company promo text as practiced in the biography/about the artist-section in digital places for music promotion – and the job application represented by the school textbook. Labelling them templates indicates stability and situation-transcendingness, and thus I link them to the vertical axis of the double dialogue. But Sasan’s texts also contain traces of other textual and social realities: for example, friends and peers commenting on the social networking site, hip hop as a known way of using skills in a culturally legitimate way to work on dreams of stardom, and school’s recurring assignment dialogue.

This brings us to a meeting point between RQ1 and RQ2: How should we conceptualize these traces, and how are these textual and contextual features that leave traces brought together to create a need. In answering RQ1, both Kristeva’s notion intertextuality and Linell’s use of situated and situation-transcending resources are appropriate. What rhetorical situation highlights is the configuration of these resources into a felt entity: a rhetorical need that comes before and configures partly the same and partly other resources into an answer. In my contention, this is what happens in the diatope. When we look for exigence, we focus on some aspects of the double dialogue and leave others in the background. As we ask what is the most pressing thing this utterance answers to, we add an element of prioritization.

This framework allows us to compare the two texts across domains and discover differences and similarities on different levels. Then we have a tool for talking more systematically about the many possible answers to RQ3: How do young people, in this specific instant, Sasan, deal textually with invitations and demands from texts and contexts?

In both texts Sasan delivers strategic self-presentations. A feature the two different rhetorical situations have in common is that Sasan has strong textual models to lean on – the textbook and the record company promo text. In Bitzerian terms we might see these as constraints, although in the double dialogue model we assign the existence of these models to the vertical axis/north pole and call them genre or preexisting texts. Yet the actualization of these models is done as part of the interaction-in-situation (in accordance with Miller (1984)).

Despite similarities when it comes to the use of textual models, and despite the fact that we can find strategic similarities between the two texts, the basic exigencies in these two situations are different. Sasan’s biography text is closely connected to his desire to be a rapper, while his job application is not connected to any desire for a job, but rather to school’s need for students to hand in assignments.

While acknowledging the different exigencies for the texts, we can still look for more strategic similarities. There is, for example, a resemblance between the fiction work in answering to a real rhetorical situation by defining a fictive one in the school assignment, and answering to the rhetorical situation ‘the need to be(come) a rapper’ by creating a more or less fictive rhetorical situation of being a rapper addressing his fans. This comparison lets us understand the text in relation to its contexts, while at the same time comparing conditions in a nuanced way, which is necessary if we are to be better at understanding young people’s writing across life spheres.

The wider relevance of analyses of this kind is that they may give us a more nuanced, yet comparable picture of the relationship between school and life in other young people’s texts. A finding after analyzing texts from school and free time from the other ten students in the underlying material in the same manner, is that, the situation-transcending textual and social norms (more stable features) play a relatively larger role in school texts than in texts from leisure time on the internet. In school, the exigence of the situation is the same across subjects, but the genre resources for each assignment vary, although they are relatively stable over time. In free time internet texts, the situation varies and more work is necessary to define the situation.

Discussion, objections, limitations

These analyses show that the use of rhetorical notions like rhetorical situation and exigence can enrich a dialogical approach to young people’s texts, and help us explore the different needs that lead to texts. They also show that hermeneutical readings that comment on the various aspects of rhetorical situation and double dialogue are suitable for detecting gaps and bridges between young people’s texts and writing in school and free time, on several levels. A better understanding of the relationship between young people’s learning and practices in and out of school has been asked for (see Dyson, 2013; Erstad, 2010). This kind of text analysis contribute to bridging this knowledge gap.

What can this kind of hermeneutically founded, dialogically-rhetorically inspired analysis offer, that other models on the market cannot? One answer is that it might give a better understanding of the purposes a text might have. In the writing wheel model, purpose is used in a generalized and anthropological way, with six purposes used as a kind of analytical frame put upon on cultures (Berge et al., 2016). In another popular model of writing – the writing triade, purpose is seen as (a part of) one angle in the triade form- content – purpose/use (Ongstad, 2004a, 2004b; Smidt, 2010). Such conceptualizations of purpose have led to didactic advice to teach students what purposes their texts have (Smidt, 2010, p. 31; Utdanningsdirektoratet, Skrivesenteret, & NAFO, 2013, p. 2). I argue that the purposes writing might have in our culture and the purpose of an actual student’s text are not exactly the same, and that the latter cannot just be derived from the first list. I also contend that it is too simplistic to presuppose a text’s purpose from the assignment formulation or from the teacher’s formulation of purpose. When we use the terms the dialogues a text takes part in and rhetorical situations and exigencies of a text, we highlight the fact that there might be several purposes at stake in one text, and that they might come from different sources and create different (sometimes opposite) exigencies. This helps us keep in mind the textual and contextual realities texts are tied to, giving them the chance to inform our analysis and understanding.

References

- Ajagán-Lester, L., Ledin, P., & Rahm, H. (2003). Intertextualiteter. In B. Englund & P. Ledin (Eds.), Teoretiska perspektiv på sakprosa. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Andersen, Ø. (1995). I retorikkens hage. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Andersson, P., & Sofkova-Hashemi, S. (2016). Screen-based literacy-practices in Swedish primary schools. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 11(2).

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1986 [1952–53]). The problem of speech genres. In C. Emerson & M. Holquist (Eds.), Speech genres and other late essays. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (1998). Local literacies: Reading and writing in one community. London: Routledge.

- Bellander, T. (2010). Ungdomars dagliga interaktion. En språkvetenskaplig studie av sex gymnasieungdomars bruk av tal, skrift och interaktionsmedier. (Doktoravhandling), Institutionen för nordiska språk, Uppsala universitet, Uppsala.

- Berge, K. L. (2005). Skriving som grunnleggende ferdighet og nasjonal prøve – ideologi og strategier. In A. J. Aasen & S. Nome (Eds.), Det nye norskfaget. Bergen: LNU/Fagbokforlaget.

- Berge, K. L., Evensen, L. S., & Thygesen, R. (2016). The wheel of writing: A model of the writing domain for the teaching and assessing of writing as a key competency. Curriculum Journal, 27(2), 172–189.

- Bitzer, L. (1968). The rhetorical situation. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 1(1), 1–14.

- Bjørgen, A. M., & Nygren, P. (2010). Children’s engagement in digital practices in leisure time and school. A socio-cultural perspective on development of digital competencies. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 5(2), 115–133.

- Blichfeldt, K., Heggem, T. G., & Larsen, E. (2006). Kontekst 8–10: Norsk for ungdomstrinnet (nynorsk ed. Vol. basisbok). Oslo: Gyldendal undervisning.

- boyd, d. (2010a). Friendship. In M. ito (Ed.), Hanging out, messing around, and geeking out. Kids living and learning with new media (pp. 79–148). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- boyd, d. (2010b). Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implication. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A networked self: Identity, community and culture on social network sites (pp. 39–58). New York: Routledge.

- Brunstad, E., Røyneland, U., & Opsahl, T. (2010). Hip hop, ethnicity and linguistic practice in rural and urban norway. In M. Terkourafi (Ed.), Languages of global hip-hop (pp. 223–255). London: Continuum International Publishing.

- Christensen, T. S., Elf, N. F., & Krogh, E. (2014). Skrivekulturer i folkeskolens niende klasse. Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

- Dewilde, J. (2017). Multilingual young people as writers in a global age. In B. Paulsrud, J. Rosén, B. Straszer, & Å. Wedin (Eds.), New perspectives on translanguaging and education (pp. 56–71). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Dyson, A. H. (2013). The case of the missing childhoods: Methodological notes for composing children in writing studies. Written Communication, 30(4), 399–527.

- Dyson, A. H. (Ed.) (2016). Child cultures, schooling, and literacy. Global perspectives on composing unique lives. London and New York: Routledge.

- Eco, U. (1981). The role of the reader: Explorations in the semiotics of texts. London: Hutchinson.

- Erstad, O. (2010). Educating the digital generation. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 2010(1), 56–71.

- Erstad, O., & Sefton-Green, J. (2013). Identity, community, and learning lives in the digital age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Evensen, L. S. (1999). Elevtekster i dobbel dialog. Om mottakere, sjanger og respons i pedagogiske skriveprosesser. In P. Linell, L. Ahrenberg, & L. Jönsson (Eds.), Samtal och språkanvändning i professionerna (pp. 49–64). Uppsala: ASLA.

- Fafner, J. (1977). Retorik: Klassisk og moderne : Indføring i nogle grundbegreber. København: Akademisk Forlag.

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gilje, Ø. (2010). Mode, mediation and moving images. An inquiry of digital editing practices in media education. Universitetet i Oslo, Oslo.

- Ilomäki, L., Taalas, P., & Lakkala, M. (2012). Learning environment and digital literacy: A mismatch or a possibility from Finnish teachers’ and students’ perspective. In: P. P. Trifonas (red.), Learning the virtual life. Public pedagogy in a digital world (pp. 63–78). New York: Routledge.

- Ito, M., Baumer, S., Bittanti, M., boyd, d., Cody, R., Herr-Stephenson, B., … Tripp, L. (2010). Hanging out, messing around, and geeking out: Kids living and learning with new media. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

- Jølbo, I. D. (2016). Identitet, stemme og aktørskap i andrespråksskriving. En undersøkelse av skriving som meningsskaping blant elever med somalisk bakgrunn i norskfaget i grunnskoleopplæringen for minoritetsspråklig ungdom. (Doktoravhandling), Universitetet i Oslo, Oslo.

- Karlsson, A.-M. (1997). Textnormer i och utanför skolan – att skriva insändare på riktigt och på låtsas. In Svenskans beskrivning (pp. 172–186). Lund: Lund University Press.

- Karlsson, A.-M. (2006). En arbetsdag i skriftsamhället: Ett etnografiskt perspektiv på skriftanvändning i vanligayrken. Stockholm: Språkrådet.

- Karlsson, A.-M., & Nikolaidou, Z. (2016). The textualization of problem handling: Lean discourses meet professional competence in eldercare and the manufacturing industry. Written Communication, 33(3), 275–301.

- Karrebæk, M. S. (2013). Fodboldskort I indskolningen: Literacy, populærkultur og polycentricitet i en minoritetsdrengs hveerdagsliv. NordAnd, 9, 9–31.

- Kristeva, J. (1986 [1966]). Ch.2: Word, dialogue and novel. In T. Moi (Ed.), The kristeva reader (pp. 34–61). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Ledin, P. (1997). “Med det nyttiga skola wi söka att förena det angenäma …” Text, bild och språklig stil i veckopressens föregångare (Vol. 14). Lund: Ledin, Per.

- Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking language, mind, and world dialogically: Interactional and contextual theories of human sense-making. Charlotte, N.C.: Information Age Publishing.

- Lüders, M. (2007). Being in mediated spaces: An enquiry into personal media practices. Det humanistiske fakultet, Universitetet i Oslo, Oslo.

- Michelsen, M. (2016). Teksthendelser i barns hverdag. En tekstetnografisk studie av åtte barns literacy og deres meningsskaping på internett. (Doktoravhandling), Universitetet i Oslo, Oslo.

- Miller, C. R. (1984). Genre as social action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 1984(70), 151–167.

- Miller, C. R., & Shepherd, D. (2004). Blogging as social action. In L. J. Gulak, S. Antonijevic, L. Johnson, C. Ratcliff, & J. Reynman (Eds.), Into the blogosphere. Rhetroric, community and culture of weblogs. Retrieved from: http://blog.lib.umn.edu/blogosphere/blogging_as_social_action_a_genre_analysis_of_the_weblog.html

- Myklebust, H.,& Høisæter, S. (2018). Written argumentation for differerent audiences. A study of addressivity and the uses of arguments in argumentative student texts. Acta Didactica, 12(3).

- Neal, M. A. (2004). No time for fake niggas: Hip hop culture and the autheticity debates. In M. Forman & M. A. Neal (Eds.), That’s the joint. The hip hop studies reader (pp. 57–60). New York: Routledge.

- Nelson, N., & Grote-Garcia, S. (2010). Text-analysis as theory-laden methodology. In C. Bazerman, R. Krut, K. Lunsford, S. McLeod, S. Null, P. Rogers, & A. Stansell (Eds.), Traditions of writing research (pp. 407–418). New York, London: Routledge.

- Nystrand, M. (1992). Social interactionism versus social constructionism: Bakhtin, rommetveit, and the semiotics of written texts. In A. H. Wold (Ed.), The dialogical alternative: Towards a theory of language and mind (pp. 157–173). Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

- Ongstad, S. (2004a). Bakhtin’s triadic epistemology and ideologies of dialogism. In F. Bostad, C. Brandist, L. S. Evensen, & S. Faber (Eds.), Bakhtinian perspectives on language and culture: Meaning in language, art and new media. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ongstad, S. (2004b). Språk, kommunikasjon og didaktikk. Norsk som flerfaglig og fagdidaktisk ressurs. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, LNU.

- Personvernombudet for forskning. Information and consent. Retrieved from http://www.nsd.uib.no/personvernombud/en/help/information_consent/

- Schultz, K., Hull, G., & Higgs, J. (2016). After writing, after school. In C. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 102–115). New York, London: Guilford Press.

- Skaftun, A., Igland, M.-A., Husebø, D., Nome, S., & Nygard, A. O. (2018). Glimpses of dialogue: Transitional practices in digitalised classrooms. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(1), 42–55.

- Smidt, J. (2010). Skrivekulturer og skrivesituasjoner i bevegelse – fra beskrivelser til utvikling. In J. Smidt (Ed.), Skriving i alle fag – innsyn og utspill. Trondheim: Tapir.

- Svensson, T. (2014). Alexander, sara og skriften. En skriftbruksetnografisk studie av barn i mellanåren. (Doktoravhandling), Örebro universitet,

- Tønnesson, J. L. (2007). Cooperation and conflict between authorial voices and model readers through rhetorical topoi in historical discourse. In K. Fløttum (Ed.), Language and dicipline perspectives on academic discourse (pp. 129–148). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Utdanningsdirektoratet, Skrivesenteret, & NAFO. (2013). God skriveopplæring – for lærere på ungdomstrinnet. 1–18. Retrieved from Utdanningsdirektoratet website: http://www.udir.no/Lareplaner/Grunnleggende-ferdigheter/Container/God-skriveopplaring---for-larere-pa-ungdomstrinnet/

- Vatz, R. E. (1973). The myth of the rhetorical situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric, 6(3).

- Villadsen, L. S. (2001). Genrebegrebet og retorisk kritik. Rhetorica Scandinavica, 2001(18), 36–49.

- Wernholm, M. (2018). Children’s shared experiences of participating in digital communities. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 13(4), 38–55.