Introduction

Explicit instruction in reading comprehension has long been a focus of research on instructional approaches to support students in understanding of fiction and expository texts (Wilkinson & Son, 2011). During recent decades, research has progressed from teaching isolated reading comprehension strategies to dialogic teaching in which these strategies are used in collaborative contexts (Lee et al., 2017; Rosenshine & Meister, 1994; Wilkinson & Son, 2011). Approaches in which explicit instruction in reading comprehension strategies is embedded in group activities, structured through the cooperative learning approach, have led to gains in students’ reading comprehension (Boardman et al, 2016; Stevens et al, 1991). In these instructional approaches, the students had the possibility to practise reading comprehension strategies in the supportive climate of small groups, in which interaction was structured to promote group cohesion. The question is, however, whether these approaches give opportunities for genuine discussion and understanding of literature or whether they may entail a risk that instruction may turn to be mechanical as teachers overemphasise reading strategies above genuine discussions. As Wilkinson and Son put it “if comprehending is a dynamic, context sensitive process, then instruction needs to be dynamic and flexible” (2011, p. 361).

This study contributes to previous research by studying classroom conversations during a Cooperative Learning and Reading Comprehension (CL-RC) intervention, in which Cooperative Learning (CL; Gillies, 2016) was combined with instruction in Reciprocal Teaching (RC; Palinscar & Brown, 1984). The lesson tasks were designed to promote students’ use of reading strategies in groups, in which interaction was structured to promote cohesion and equal participation. The conversations were studied through the lens of the theory of envisionment building (Langer, 2011), emphasising how students form understandings of literature and create literary experiences in the course of reading and discussing texts.

Interpreting and understanding texts as envisionment building

As students get involved in literary texts, they become engaged in the process of interaction with a given text. This process can be described as “envisionment” (Langer, 2011, p. 11), following the theoretical line of reasoning in which the reader’s interpretation of the text at hand is focused to gain knowledge of students’ literary understanding (Iser, 2010). In accordance with Langer (2011), envisionment building is developed by the reader and is in a state of constant change as the reader’s understanding fluctuates between grasping the gist of the text as a whole and momentary understanding of the text. In this complex process, there are stances or options that offer different perspectives or “vantage points” (Folkeryd et al., 2006; Langer, 2011, p. 17). Five such stances have been distinguished (Langer, 2011, pp. 16–21): “being out and stepping into an envisionment” (e.g. picking up separate clues); “being in and moving through an envisionment” (e.g. becoming immersed in the text and making connections); “stepping out and rethinking what one knows” (e.g. relating it to one’s own experiences); “stepping out and objectifying the experience” (e.g. focusing on the author’s craft and literary elements); and “leaving an envisionment and going beyond” (e.g. using one’s well-developed envisionment in new situations).

According to Langer (2011), the stances of envisionment do not occur in a linear fashion. Rather they constitute different perspectives in the process of interpreting and understanding a given text or, as Judith Langer (2011) suggests, “we filter our thoughts through slightly different vectors” (p. 21) as we read. In the beginning the reader may have a few clues and ideas, which shift and round out as time passes. The stances occur and recur during the process of reading. For example, the first stance, “being out and stepping into an envisionment”, may occur not only in the beginning as a reader starts to build his or her understanding of a text, but also later on when a new event in a story may urge the reader to “search for starting places to rebuild envisionment” (Langer, 2011, p. 18). Together, the stances described above may provide an analytical tool to describe patterns of students’ literary understanding in classroom discussions.

Envisionment building and classroom discussions

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated complex interventions combining cooperative learning and reading comprehension through the lens of the processes of envisionment building. Research has focused on quantitative evaluations with regard to students’ reading comprehension abilities (Boardman et al., 2016; Klang et al., 2022; Stevens et al., 1991). It is important, however, to get a deeper insight as to which prerequisites for student literary understanding are created through these interventions, since they represent a specific approach to reading comprehension instruction, emphasising student thinking about strategies when reading texts and to a lesser degree attending to text ideas per se (McKeown et al., 2009).

Previous studies, in which classroom instruction was studied through Langer’s theory of envisionment building (Langer, 2011), unravelled evolving patterns of students’ literary understanding as they interacted with fiction texts. When teachers ask carefully considered questions, their students’ responses show signs of varied stances of envisionment building (Håland & Hoel, 2016; Zapata et al., 2018). However, encouraging students to move between stances or vantage points in relation to texts may be a challenging task. In a design-based intervention study by Norberg and Hjalmarsson (2022), a mother tongue teacher of Russian scaffolded her students understanding of literary texts in classroom discussions. Students’ responses in the discussions focused primarily on text contents (stance one and two) or on relating texts to their own lives (stance three). It was not until the final discussions that the students could delve deeper into texts and objectify their experiences (stance four) through well-designed activity and with teacher support. The researchers pointed out that moving between the stances of envisionment in the discussions enabled students to create links between fictive characters and students’ lives, to disentangle the events of the story and finally distance themselves from the immediate text contents and reflect on the message of the text at hand.

A study by Economou (2015) focused on group discussions in one classroom in Swedish upper-secondary school. The discussion in the groups focused on book quotations that affected students. Teacher questions served to facilitate the understanding of texts and student questions were encouraged. Economou (2015) found that in group discussions the students tended to relate the contents of the novel to their personal lives (stance three). This finding is encouraging since Langer (2011) pointed out that this stance of envisionment building constitutes a way to understand one’s personal experiences through literature and is “the primary reason for why we read and study literature” (p. 20). Folkeryd et al. (2006) and Liberg et al. (2012) pointed out that this stance may be challenging in literacy instruction as students may feel they are expected to focus on text contents rather than their personal experiences. Thus, the instructional activities and students’ active roles in discussions of texts in Economou’s study may have played an important role in creating prerequisites for students’ literary experiences.

The instructional organisation of discussions about texts in group activities in Economou’s study highlights the potential role of peers in students’ literary understanding. Researchers pointed to the importance of genuine discussions, in which students are viewed as active envisionment builders (Applebee, 2003) and are given larger responsibility in interpreting texts and voicing their perspectives (Lawrence & Snow, 2010). Genuine discussions can further be explained with the help of Langer (2011) as discussions in which tensions and balances are recognised and all the members are allowed to voice their understandings of texts. Peer group discussions may be particularly important in this regard, especially for struggling readers. Participation in group work discussions may, with time, provide students who experience difficulties in reading with possibilities to observe their peers’ use of comprehension strategies and become comfortable voicing their opinions (Hall, 2012).

In addition to peers’ contributions to the understanding of texts, the teachers have a profound role in promoting students’ literary understanding of texts. Several decades of classroom research have revealed specific teacher moves that promote students’ literacy learning in general and understanding of texts in particular (Applebee et al., 2003; Lawrence & Snow, 2010; Nystrand, 2006). These include encouraging multiple views (Applebee et al., 2003), asking authentic questions and following up on students’ contributions by marking and verifying them (Lawrence & Snow, 2010) or building upon and incorporating student answers in whole-class discussions (Nystrand, 2006). Recent studies, taking the point of departure from the theory of envisionment building (Langer, 2011), have also brought to light challenges in teacher questioning in the classroom, as formulating questions that encourage deeper understanding (Norberg & Hjalmarsson, 2022) or extending discussions so that these do not resemble the traditional initiation-response pattern of instructional talk (Håland & Hoel, 2016). With regard to the importance of both teachers and peers in classroom discussions, there is a need for more research on peer-led versus teacher-led discussions and the unique opportunities both types of discussion offer for understanding of literary texts (Lawrence & Snow, 2010).

Current study

In previous research, the importance of explicit reading comprehension instruction in collaborative contexts has been emphasised (Wilkinson & Son, 2011). Several intervention studies, in which instruction in reading comprehension strategies is embedded in group activities, have been shown to promote student reading comprehension (Boardman et al., 2016; Stevens et al., 1991). However, to the best of our knowledge, previous research has not focused on an in-depth study of the prerequisites for student literary understanding in these studies. This study is a part of a larger project, in which intervention, combining instruction in reading comprehension strategies and structured groupwork through cooperative learning (Cooperative Learning and Reading Comprehension, CL-RC), was evaluated (Klang et al., 2022). The study aims to gain a deeper understanding of students’ literary understanding of texts that occurred in three lessons, using one module of the intervention project. Using the theory of envisionment building (Langer, 2011), the focus is on the stances of envisionment that characterise peer-led and teacher-led classroom discussions about the short story “The Invisible Child” (Jansson, 1962). The co-constructed literary understanding created in the classroom is illustrated with the help of excerpts from student and teacher conversations.

The following research question is in focus for the study: What stances of envisionment building characterise peer-led and teacher-led classroom discussions during CL-RC intervention?

Method

One module of intervention, comprised of three lessons designed in accordance with the CL-RC approach, was video recorded and the peer-led and teacher-led discussions were analysed with regard to stances of text envisionment building (Langer, 1995; 2011). Ethical approval was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2017/372) prior to the start of the study.

Study participants

Mrs Stone is a mother tongue teacher with 13 years’ teaching experience, including two years of teaching in the participating class. Mrs Stone was selected to the study, as she was actively engaged in the development of instructional materials during nine months before the start of the experimental evaluation of the intervention described previously (Klang et al., 2022). Thus, Mrs Stone had profound knowledge and experience of the CL-RC approach. Informed consent from the students’ parents in Mrs Stone’s class was obtained for 20 out of 30 twelve-year-old students. The students for whom no consent was obtained, participated as usual in the lessons but their group discussions were not videorecorded. Information about the study was also distributed to the students and the researchers renegotiated students’ informal assent to participate in the videorecorded activities throughout the whole study. The school was situated in the centre of a middle-sized town and the class was heterogeneous with regard to students’ backgrounds and educational needs. However, no information on students’ prerequisites for or interest in reading fiction texts was collected.

CL-RC intervention

The CL-RC intervention combined elements of small group work in accordance with cooperative learning approach and reading comprehension instruction in accordance with the approach of reciprocal teaching. Cooperative learning was organised in accordance with the CL approach (Gillies, 2016; Johnson et al, 2009; Klang et al., 2022). Students worked in heterogeneous groups of three or four and the classroom was organised so that the students were seated together and faced each other in the discussion. The collaboration in the groups was highly structured to promote cooperation and individual responsibility for the task at hand. This was done by giving students complementary roles in the discussion (e.g. chairman, secretary, or encourager) or structuring the discussion through tasks in which each student’s contribution was required. For each lesson there was a social skill to practise (e.g. listening to each other or giving feedback in a constructive way), and time was allotted for reflection on the group’s work (Gillies, 2016; Johnson et al., 2009).

Reading comprehension in small groups focused on four comprehension-fostering activities (Palinscar & Brown, 1984): predicting, clarifying, questioning, and summarising. In this study, the students were not explicitly taught reading comprehension strategies. Rather, the strategies were embedded in activities and tasks throughout the lessons. First, the strategy of predicting encourages students to make inferences about texts and test these in the process of subsequent reading (Palinscar & Brown, 1984). In the current study, the students were asked to discuss two illustrations from the story which portrayed the main character being invisible. Second, the strategy of clarifying, intends to promote a critical evaluation of the content (Palinscar & Brown, 1984). The intervention module included peer discussions of unfamiliar words and phrases chosen by students and predetermined by the researchers in the module.

The third and fourth strategies, questioning and summarising, are supposed to direct student attention to major content of a given text and check their understanding (Palinscar & Brown, 1984). Questioning was practised by providing questions of varying complexity in the module – from gathering and searching for information to making inferences from larger portions of text (see Table 1). Summarising was focused by asking the students to discuss what the problem in the story was and how it was solved. All these activities were embedded in peer-led and teacher-led discussions.

In Table 1, the activities in each of the studied lessons are described with regard to the four comprehension-fostering strategies of reciprocal teaching (Palinscar & Brown, 1984). As seen in the table, the activities of predicting the plot of the story and summarising its storyline were focused on in the first and the second lesson. Time was allotted to activities of clarifying words and phrases in two lessons. Questions of varying complexity were focused on in all the three lessons. While the goal was to successively shift the responsibility of formulating questions from the teacher to the students, this was not achieved in the three lessons of the intervention that were focused on in this study.

When using the modules based on the principles of cooperative learning and reciprocal teaching, Mrs Stone relied on her previous teaching experience and considered students’ needs when she allocated time to the activities. Initially, Mrs. Stone allotted her students to small heterogeneous groups of three to four pupils. When teaching, she switched between group work and classroom discussions, so that each task was first conducted in group and then discussed in whole class. Thus, discussions in which peers took responsibility for the conversation and turn-taking in groups (peer-led discussions) and discussions in which teacher was the one who asked questions and distributed the word (teacher-led discussions) were alternated.

The module focused on in this study is the short story “The Invisible Child” (Jansson, 1962). The story revolves around a child, Ninni, who is taken into care by the Moomin family. When Ninni arrives at the Moomin’s home, she is invisible because she was treated badly by her former carer, but she eventually becomes visible as she receives warmth and care from the Moomin family. This story serves as a good groundwork for discussions about ideas behind a text as it contains multiple layers of interpretation. At first glance, the story contains easily identifiable events as Ninni, the invisible child, receives specific treatment from the Moomin family, such as a home-made cure or a warm bed, in order to make her visible. However, beyond these examples, there is the idea of the importance of being seen and accepted by others and the importance of the warm, friendly attitudes and support of others.

| Predicting | Clarifying | Questioning | Summarising | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesson 1 | Predicting the plot of the story from pictures (peer discussions)

What do you see in the picture? What people and events are portrayed? What do you think the story is about? |

Underlining unfamiliar words and discussing their meaning (peer and teacher discussions) | How did Ninni become invisible?

What led to Ninni becoming visible again? (peer and teacher discussions) |

|

| Lesson 2 | Clarifying difficult words suggested by the teacher, e.g., remedy, bell, zealous, ironic (peer and teacher discussions) | What is the story about? What is the problem? How is it solved? (peer and teacher discussions) | ||

| Lesson 3 | What characters were important for Ninni becoming visible? (peer and teacher discussions) |

Data collection

The videorecordings of the lessons were conducted with two cameras, one placed at the back of the classroom facing the teacher and the other shooting a group of students. Besides, two microphones were placed on the desks of two student groups. The duration of the recorded lessons was 152 minutes.

Data analyses

The video recordings were transcribed verbatim and divided into discussion sequences, defined as a sequence of communicative turns between teacher and students focusing on the same theme (Wells, 1999). The discussion sequences were often naturally marked by transitions between tasks during the lessons. A total of nine peer-led and five teacher-led discussion sequences were analysed.

In the discussion sequences, each separate utterance was categorised in accordance with stances of envisionment building (Folkeryd et al., 2006; Langer, 1995), with inspiration from previous studies which used this analytic framework in analyses of classroom discussions (e.g. Economou, 2015; Håland & Hoel, 2016). The categorisation was conducted during recurring meetings between the first, the second and the third author, with the second author taking the overall responsibility for the final categorisation results. During the meetings all the three authors’ perspectives on categorisation were discussed and eventual disagreements were resolved. The number of utterances in the three lessons in peer-led discussions was 148 and 170 in teacher-led discussions. Five categories related to stances of envisionment building were assigned to the students’ and teachers’ utterances. The different categories are described below and are complemented by examples of utterances from the discussion of the story “The Invisible Child” (Jansson, 1962).

The first stance, “being out and stepping into an envisionment”, was assigned to utterances in which students selected separate facts from the texts such as “The mother (the Moomin mother) made her bed and said she could ask her about anything she wanted”. The second stance, “being in and moving through an envisionment”, was assigned to utterances in which the students summarised and interpreted larger portions of text by referring to the main idea or underlying meaning. The students looked beyond the literal meaning in the text in order to enrich their understanding and to evaluate the text contents. The following utterance illustrates this stance: “Right and it did not matter that it fell [a can that Ninni dropped]. She knew it was ok. Nobody got angry at her and she therefore felt safe.” This idea was not explicitly expressed in the text and required the students to draw conclusions based on specific facts in the text.

The third stance, “stepping out and rethinking what one knows”, was evident in utterances in which the students related the text contents to their own experiences and thoughts, for example, “Just imagine being invisible. Then you could sneak around and hear all the things that people were saying about you”. The fourth stance, “stepping out and objectifying the experience”, involved discussing the text in relation to its purpose and the author’s intentions and was not evident in student utterances. Therefore, an example in the following utterance by the teacher is provided: “What is the author trying to say with this story?” The fifth stance, “leaving an envisionment and going beyond”, referred to using well-developed envisionment of the text in a new and unrelated situation. No utterances in peer- or teacher-led discussions could be related to this stance. An example of this stance could have been students’ making connections between their understanding of the story at the beginning and their understanding at the end of the story, making comparisons and reflections.

Some utterances were too short to categorise and were coded as “not possible to code”, for example “the dress” (referring to Ninni’s dress). In the categorisation of these utterances, the context of the utterance was given specific attention. Utterances referring to the organisation of tasks such as “I have no pen” or “Shall we take the next question?” were excluded from the analysis.

Results

Having categorised the utterances of each student and teacher, we summarised the utterances associated with specific stances of envisionment building per lesson and type of discussion (i.e., peer- or teacher-led). Further, we chose discussion sequences over the course of the three lessons to illustrate how the students and Mrs Stone co-constructed their understanding of the ideas in the story.

Stances of envisionment characterising peer-led and teacher-led discussions

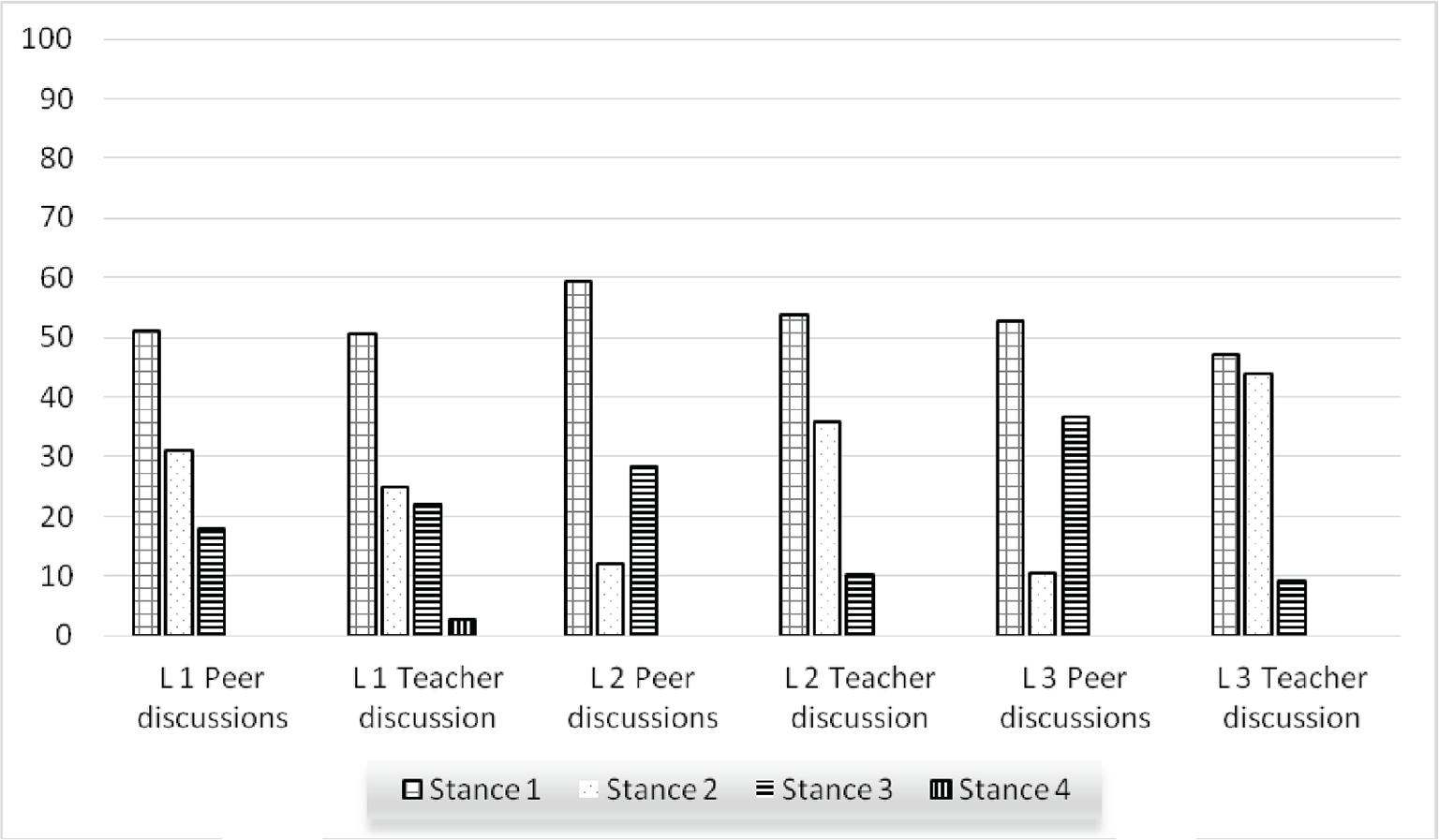

In Figure 1, the proportion of utterances categorised as stances of envisionment are reported per peer- and teacher-led discussions over the three lessons. As seen in the figure, the first stance “being out and stepping into an envisionment” was the stance that characterised the utterances in both peer- and teacher-led discussions in all the three lessons. Thus, in the course of discussions about the story, the students in Mrs Stone’s class picked up clues and ideas in texts in order to develop their understanding. It is important to point out that the second stance, “being in and moving through an envisionment”, characterised a considerable proportion of teacher-led discussions and a smaller proportion of peer-led discussions. The proportion of utterances related to this stance also increased in teacher-led discussions over the course of the three lessons. Thus, in the teacher-led discussions, both teacher’s and students’ utterances were characterised not only by stepping into the text worlds, focusing on superficial text clues, but also becoming immersed in the text worlds, elaborating and making connections.

The third stance, “stepping out and rethinking what one knows”, on the other hand, is evident to a larger degree in peer-led discussions and it also increases over the course of the three lessons. The fourth stance, “stepping out and objectifying the experience”, was assigned to only one utterance in teacher-led discussion. The fifth stance, “leaving an envisionment and going beyond”, was not noted in either peer- or teacher-led discussions.

Illustration of how students and teachers co-constructed their literary understanding of the story in the course of three lessons

The sequences from the peer-led and teacher-led discussions below serve as examples of how the students and teachers created meaning from the story “The Invisible Child” (Jansson, 1962).

Lesson 1. Getting initial ideas about the plot of the story

During the first lesson, the students engaged in activities of predicting the plot of the story, clarifying unfamiliar words and discussing the question of how Ninni became invisible and how she eventually became visible again.

Example 1. How did Ninni become invisible? Stepping into the text and searching for clues

The following peer-led discussion unfolded in the task of finding evidence in the text as to why and how the main character Ninni became invisible.

[1] Dennis: She was frightened

[2] Garry: By someone who

[3] Dennis: That lady she was living with

[4] Garry: Yeah she was mean and ironic

[5] Evert: Yeah and she became invisible

In this discussion the students in the group turn to the specific facts in the text in their search for clues and ideas and the utterances were categorised as “being out and stepping into an envisionment”. In these lines, the students are picking up clues in the text pointing to Ninni’s carer (utterance 3) and pointing to the fact that she was ironic (utterance 4), which is explicitly stated in the text.

Example 2. Why did Ninni become visible? Stepping into and moving through the envisionment

In another task, the students were asked to find evidence of how and why Ninni became visible again. The following sequence reveals a group discussion.

[6] Dennis: Yes, they

[7] Evert: They gave her some kind of tea

[8] Garry: They gave her some kind of cure and then they took good care of her

[9] Evert: Yes, they took good care of her and she felt sort of loved

[10] Dennis: Yes, appreciated

[11] Evert: And then so

[12] Dennis: So

[13] Evert: Yes and her feet became visible

[14] Dennis: A foot

Some of the utterances in the sequence correspond to the first stance, “being out and stepping into an envisionment”, (utterances 7 and 13) and describe how students created their understanding of the text by focusing on specific facts. Other utterances relate to the second stance, “being in and moving through the envisionment”, (utterances 9–10) and illustrate how these students used these facts to develop their understanding of the whole text and the ideas behind it.

Example 3. Mrs Stone is gathering the clues and suppositions – stepping into and moving through the envisionment

This excerpt describes a teacher-led classroom discussion of how Ninni became visible and what particular events in the story may have been responsible for this

[15] Fia: Maybe she feels safe in the family?

[16] Mrs Stone: Maybe she feels safe in the family? You think so, but then you mention coffee. She added something to the coffee. These are the two things you are saying. Does someone else want to elaborate on the idea? She is taken care of. Does someone want to elaborate?

[17] Anna: She’s not scared anymore

[18] Mrs Stone: She’s treated better. She’s not scared anymore. Is there anything else?

[19] Henrik: When Moomin’s mother makes her bed and tucks her in, she feels like one of the family and her foot became visible again

[20] Mrs Stone: Something more about feeling safe in the family? What does the family do?

[21] Irvin: They are very welcoming and tell her she can sleep as much as she wants. They give her food and things

[22] Mrs Stone: Yes, welcoming, she can sleep as much as she wants, food and things. This is a welcoming gesture. Maybe this all creates the sense of safety that we’re talking about and makes her visible. Does anyone else want to add anything?

The students’ utterances in the sequence shift between the first stance, “being out and stepping into an envisionment” (utterance 19 and 21), and the second stance, “being in and moving through the envisionment” (utterance 15 and 17). Some of Mrs Stone’s utterances include both the first and the second stances of envisionment building (utterance 16 and 22). Mrs Stone asks questions and gives comments that direct the students’ attention to both specific facts in the story as well as to the meaning of these facts in Ninni’s process of becoming visible. Further, Mrs Stone repeats students’ contributions (utterance 18) to promote discussion and summarises the discussion, marking its central parts.

Lesson 2. Summarising the storyline and delving deeper into the meaning of words

During the second lesson the students worked with the task of summarising the storyline and discussed expressions and words from the text, suggested by the teacher. One of the words, ironic, had a central meaning in the text and it was the ironic commentaries of Ninni’s carer that lead her to become invisible.

Example 1. What is the story about – a child, a family, or a troll?

The students were instructed by the teacher to summarise the story and the discussion focuses on what the story is about, what the problem is and how it is solved.

[23] Evert: It is about a moomintroll, they are called Moomintrolls

[24] Garry: Yeah, but she was not a troll

[25] Evert: No, but it’s about the one who is invisible

[26] Dennis: No it’s about a family

[27] Evert: No it’s about a Moominfamily that gets to take care of a child who got invisible

[28] Garry: But it’s also about a child

[29] Dennis: This child got invisible ‘cause its foster mom or what it was has lied to her

[30] Evert: She was sarcastic

In this discussion sequence the students in the group exchange their ideas about the main characters of the story. The utterances in the sequence refer to the first stance, “being out and stepping into an envisionment”, and are focused on specific details, exposed in the text, as Moominfamily (utterances 23–25). Other utterances illustrate instances in which the students try and test their ideas of what the meaning of the events in the text is (utterances 27–29) and thus refer to the second stance, “being in and moving through the envisionment”.

Example 2. Mrs Stone summarises the discussion and the class is being immersed in the text and focuses on gathering facts

After allocating time to peer-led discussions, Mrs Stone summons the class in the common discussion of the summary of the story.

[31] Mrs Stone: So you got some minutes to discuss: who is the story about?

[32] Evert: Moomintrollen and the invisible child

[33] Mrs Stone: Moomintrollen, the group, this family and an invisible girl. And what is the problem in the story?

[34] Evert: She got scared so much that she got invisible

[35] Mrs Stone: The girl got scared so much that she got invisible. Okay and what does the family have to do with her? Is she a family member? How do they know each other? Dennis.

[36] Dennis: Someone who’s called Toticki took her with him ‘cause he knew they were kind

[37] Mrs Stone: Dennis supposes that it is that the family is kind and will take care of the child okay and how was the problem solved?

[38] Dennis: The family has tried to be extra welcoming to her and the mother mixed some kind of remedy in her drink

[39] Mrs Stone: Okay there are two ways to see it. One is that they were nice. How were they nice to her, can someone give an example?

[40] Fia: Moominmother tucked her in and said to her she could ask for whatever

[41] Gina: They said she could stay with them

The start of the discussion is characterised by the first stance, “being out and stepping into an envisionment”. In their efforts to summarise the text, the students bring up different clues from the text (utterances 31–34). Mrs Stone’s question (utterance 35) sparks Dennis’s speculation about the meaning of the characters in the story. Further on in the discussion, the students’ utterances stretch beyond the explicit facts of the story (utterance 38 and 41). Mrs Stone summarises the students’ utterances, emphasising multiple points of view (utterances 37 and 39) and uses them to advance the conversation.

Example 3. Delving more deeply into the meaning of words

In the following discussion, the students in one of the groups set out to explore the meaning of the word “ironic”, which was of central importance in the story.

[42] Fia: Ironic, it is when you say things that you don’t mean, right?

[43] Gina: Yeah you can say kind of, I can always say yeah sure, no like this yeah sssure

[44] Henrik: Yeah

[45] Gina: Then I am ironic, it can be when you say one thing but you don’t really mean it

The students’ utterances in this sequence were referred to the third stance of envisionment building, “stepping out and rethinking what one knows”. When discussing the meaning of words, the students shift focus from the in-text world to their personal experiences.

Lesson 3. Relating the story to one’s own life and exploring the role of specific characters

During the third lesson the students discussed the importance of different characters in the story for Ninni becoming visible.

Example 1. Imagine being invisible by stepping out of the text-world

The following discussion sequence unfolded spontaneously and was not prompted by a specific teacher question.

[46] Fia: Just imagine being invisible

[47] Gina: You may be

[48] Henrik: It would be cool for two days

[47] Gina: And then you would get tired of that

[48] Fia: But you could sneak around and do whatever you wanted to and know if somebody was talking behind your back

The utterances in this sequence reflect the third stance of envisionment, “stepping out and rethinking what one knows”. The students discuss the fact that Ninni becomes invisible and try to imagine the benefits of being invisible, linking the fictive and real worlds.

Example 2. Why does being angry make you visible? Being in and moving through the envisionment

This teacher-led discussion followed a peer-led discussion on the contribution of different characters in the story in Ninni’s process of becoming visible. One character, the Little My, in her rebel-like way, encouraged and praised Ninni when she bit the Moomin dad when she was angry, which caused Ninni to become completely visible. This is a key event in the story as it demonstrates the importance of unconditional love and support from friends and next of kin.

[49] Mrs Stone: Why do you think giving praise in this situation helped Ninni to become visible?

[50] Dennis: Maybe it was wrong. It was not a good thing to do?

[51] Mrs Stone: Yes, you shouldn’t bite people. But what was good about Ninni’s biting? It’s not good to bite others, but what was good in Ninni’s case?

[52] Julia: She was brave enough to do something!

[53] Mrs Stone: Yes, she was brave enough to do something and not just following others and she was brave enough to follow her own feelings.

The sequence contains utterances related to the second stance, “being in and moving through an envisionment”. In this teacher-led discussion, the teacher asked the students to elaborate on the key events in the story (utterances 49 and 53), encouraging them to reflect on the meaning of the events and the roles of the characters in the story. In the course of this discussion, the students elaborated on the meaning of the events (utterances 50 and 52) and focused on understanding the story’s underlying message. Mrs Stone acknowledged the students’ suggestions and further accentuated the key elements of the story, moving between the first and the second stances of envisionment (utterance 53).

Discussion

This study intended to contribute to previous research by studying students’ literary experiences and processes of understanding and interpreting texts in an intervention which combined cooperative learning and instruction in reading comprehension strategies (CL-RC). Blending these two instructional approaches in one intervention was supposed to create a group climate, supportive of open discussions, in which students would be encouraged to practise reading comprehension strategies. Despite the established benefits of collaborative approaches, involving instruction in reading comprehension strategies (Boardman et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017; Rosenshine & Meister, 1994; Stevens et al., 1991), researchers have raised questions as to whether these give rise to genuine classroom discussions fostering dynamic and flexible understanding of texts (Wilkinson & Son, 2011). This study, following the theoretical line of reasoning on the importance of reader’s interpretation of texts (Iser, 2010), used Langer’s concept of stances of envisionment building (Folkeryd et al., 2006; Langer, 1995, 2011) to study how students and their teachers developed their understanding of a story, “The Invisible Child” (Jansson, 1962) during three lessons of one module of the CL-RC intervention. Using this theory as an analytical tool enabled a more nuanced study of students’ literary experiences beyond the quantitative evaluation of the intervention with regard to students’ reading comprehension, previously reported in this journal (Klang et al., 2022).

The results of the study showed that both peer- and teacher-led discussions in the videorecorded lessons were characterised by the first stance, “being out and stepping into an envisionment”, and the second stance, “being in and moving through an envisionment”, (Langer, 2011). Thus, in both peer and teacher discussions, the students made sense of text-worlds, switching between picking up separate clues and looking beyond these clues to make connections between the meaning of different events and the details of the story. It is evident from the sequences in which Mrs Stone interweaves the first and second stances as she asks for details from the story to support students’ suppositions about the meaning of the story’s events. These discussions, characterised by close ties to text contents, may provide a unique opportunity for students to disentangle the events of a text at hand and to delve deeper into text contents before the students can distance themselves from the text and objectify their experiences (Norberg & Hjalmarsson, 2022). The fluctuations in positioning between the first and the second stances of envisionment building may thus constitute an important aspect of teaching for literary understanding.

Teacher-led discussions were characterised by the second stance, “being in and moving through an envisionment” to a higher degree. These discussions offered opportunities to become immersed in text worlds and to look beyond the particular text events to the underlying meanings and main ideas. Lawrence and Snow (2010) as well as Nystrand (2006) point to the importance of teacher moves, such as modelling, marking, and verifying student understandings, asking authentic questions, and following up on student contributions. These were visible in teacher-led conversations in this study as Mrs Stone directed the students’ attention to specific events and the meaning of these for the main character, Ninni (e.g., utterances 16 and 22). Furthermore, Mrs Stone repeated and summarised student contributions (e.g., utterance 28) and sparked student thinking further (e.g., utterance 35). In this study the focus has been on the possibilities rather than constraints in teacher-led conversations. However, with regard to challenges in teacher questioning for literary understanding (Håland & Hoel, 2016; Norberg & Hjalmarsson, 2022), there may be a need to accentuate attention on how teacher questions could be formulated to support movements between the stances of envisionment building in classroom discussions.

Peer-led discussions, on the other hand, were characterised by the third stance, “stepping out and rethinking what one knows”, which also increased over the course of the three lessons. Thus, the students stepped out of the text world, relating the text contents to their own experiences. Similar results have been found in a study of group discussions by Economou (2015), in which students’ discussions were characterised by the students’ relating the contents of the book to their personal experiences.

Langer (2011) points to the importance of the third stance of envisionment, as it allows students to use text-worlds to add to their experiences rather than using their experiences to understand texts. In this way, according to Langer, the fictive and real worlds intersect, enriching students’ literary experiences. This stance could be particularly important for students who have not developed a deep understanding of a given text thus far (af Geijerstam, 2014), but it may also be challenging as students may be influenced by perceived expectations of focusing on the text at hand rather than their experiences of the text (Folkeryd et al., 2006; Liberg et al., 2012). One conclusion from the current study is that the small group discussions, structured in accordance with cooperative learning, may be supportive of literary understanding, as it enables relating text ideas to students’ own experiences. Langer (2011) emphasised the importance of a nurturing climate for discussions on literature in which all the members are encouraged to voice their understandings of texts. The value of the cooperative learning approach in this regard may lie in the application of principles to improve group cohesion, such as complementary roles for group members, accentuating social skills of listening and giving feedback, as well as allotting time for reflection on group work (Gillies, 2016; Johnson et al., 2009). The discussion sequences analysed in this study did not however specifically focus students’ use of roles or listening and giving feedback to each other in groups. Incorporating the elements of group work structures in the analyses of students’ literary understanding may shed further light on the potential of the CL-RC intervention in enriching students’ discussions of fiction texts.

The fourth stance, “stepping out and objectifying the experience”, and the fifth stance, “leaving an envisionment and going beyond”, did not characterise peer or teacher-led discussions. In fact, the fourth stance was noted only once in teacher-led discussion and the fifth stance did not appear in the discussions. Thus, the students’ literary experiences in the lessons of CL-RC module did not extend to discussions of literary elements of the text or discussions in which students’ acquired envisionment was used in novel situations. For example, the students were not given opportunities to explore why the author used the figurative language of being visible and invisible or how this figurative language could extend to unrelated situations. The opportunities to build envisionments of the text may thus have been limited in the studied module. These limitations may be attributed to the focus on reading comprehension strategies as these were used in this intervention, which may have constrained possibilities for the students to take different “vantage points” (Langer, 2011) in relation to the texts. The reading comprehension strategies were not explicitly taught in the CL-RC intervention but were rather embedded in the activities in the module. Furthermore, as seen in Table 1, the wording of instructions and questions for the strategies of summarising, clarifying and predicting as well as questioning in this study were bound to the plot of the story and were locally situated in the texts. They did not extend beyond or above the text contents. The results may thus be attributed to the design of the study per se and may not shed light on the challenges associated with opportunities for genuine discussions in reading comprehension interventions, as outlined in previous research (McKeown et al., 2009; Wilkinson & Son, 2011).

To conclude, this study intended to provide insight into students’ discussions manifesting their literary understanding in the course of CL-RC intervention and to generate a qualitative description of an intervention study, previously published in this journal (Klang et al., 2022). The results of the current study indicate that although the CL-RC intervention module may have created possibilities for disentangling story events and relating the story contents to students’ personal lives, it may have had resulted in limited openings for reflection on literary text elements or use of acquired knowledge in novel situations. The results may be attributed to a number of factors, including the design of the module, the complexity of the intervention integrating two instructional approaches as well as teacher questioning and conversational moves. The results, however, may also be ascribed to factors that were not accounted for in the study as students’ prerequisites for and interest in fiction texts as well as teacher’s beliefs about teaching in general and literacy instruction in particular. These factors are yet to be uncovered in order to fully understand the meaning of the CL-RC intervention for the involved students and teachers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Caroline Liberg, Åsa af Geijerstam, and Åsa Persson for their support in the design of the study. We would also like to express our gratitude to Rights and Brands Moomin for permission to use the story “The Invisible Child”.

References

- af Geijerstam, Å. (2014). Läsandet och sammanhanget: Läspositioner i olika ämnen i skolan [Reading and context: Reading positions in different school subjects]. In A. Boglind, P. Holmberg, & A. Nordenstam (Eds.) Mötesplatser: Texter för svenskämnet. Studentlitteratur.

- Applebee, A. N., Langer, J. A., Nystrand, M., & Gamoran, A. (2003). Discussion-based approaches to developing understanding: Classroom instruction and student performance in middle and high school english. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 685–730. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040003685

- Boardman, A. G., Vaughn, S., Buckley, P., Reutebuch, C., Roberts, G., & Klingner, J. (2016). Collaborative strategic reading for students with learning disabilities in upper elementary classrooms. Exceptional Children, 82(4), 409–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402915625067

- Economou, C. (2015). Reading fiction in a second-language classroom. Education Inquiry, 6(1), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v6.23991

- Folkeryd, J. W., af Geijerstam, Å. & Edling, A. (2006). Textrörlighet – hur elever talar om egna och andras texter. [Text mobility – how students talk of their texts and the texts of others]. In L. Bjar (Ed.), Det hänger på språket. Studentlitteratur.

- Gillies, R. M. (2016). Cooperative learning: Review of research and practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2016v41n3.3

- Hall, L. A. (2012). Moving out of silence: Helping struggling readers find their voices in text-based discussions. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 28(4), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2012.702037

- Håland, A., & Hoel, T. (2016). Leseupplæring i norskfagets begynnelsesopplæring med fokus på fagspesifikk lesekompetanse [Early reading instruction in Norwegian with an emphasis on specific reading competence]. Nordic Journal of Literacy Research, 2, 21–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.17585/njlr.v2.195

- Iser, W. (2010). Interaction between text and reader. In P. Simon (Ed.), The Norton anthology of theory and criticism (pp. 1524–1532). Norton and Company.

- Jansson, T. (1962). Berättelsen om det osynliga barnet [The story of the invisible child]. © Tove Jansson 1962 Moomin Characters™.

- Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Johnson Holubec, E. (2009). Circle of learning: Cooperation in the classroom. Interaction Book Company.

- Klang, N., Åsman, J., Mattsson, M., Nilholm, C., & Wiksten Folkeryd, J. (2022). Intervention combining cooperative learning and instruction in reading comprehension strategies in heterogeneous classrooms. Nordic Journal of Literacy Research, 8(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.23865/njlr.v8.2740

- Langer, J. A. (1995). Envisioning literature. Literary understanding and literature instruction. Teachers College Press.

- Langer, J. A. (2011). Literature. Literary understanding and literature instruction. (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

- Law, Y. (2014). The role of structured cooperative learning groups for enhancing Chinese primary students’ reading comprehension. Educational Psychology, 34(4), 470–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.860216

- Lawrence, J. F., & Snow, C. E. (2010). Oral discourse and reading. In M. L. Kamil, P. D. Pearson, M. E. Birr, P. Afflerbach, & P. B. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of reading research, volume IV. Routledge.

- Liberg, C., af Geijerstam, Å., Wiksten Folkeryd, J., Bremholm, J., Hallesson, Y. & Holtz, B.-M. (2012). Textrörlighet – ett begrepp i rörelse [Text mobility – a concept in motion]. In S. Matre & A. Skaftun (Eds.) Skriv! Les! Artikler fra den forste nordiske konferense om skrivning, lesing og literacy [Write! Read! Articles from the first Nordic conference on writing, reading and literacy]. Akademika.

- McKeown, M. G., Beck, I. L., & Blake, R. G. K. (2009). Rethinking reading comprehension instruction: A comparison of instruction for strategies and content approaches. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(3), 218–253. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.44.3.1

- Norberg, A.-M., & Hjalmarsson, A. (2022). Budskap bortom raderna – en modersmålslärares stöttning av yngre elevers tolkande läsning av skönlitteratur [Scaffolding of primary school students’ interpretive fiction reading in Russian as a mother tongue in Sweden]. Nordic Journal of Literacy Research, 8(11), 22–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/njlr.v8.3212

- Nystrand, M. (2006). Research on the role of classroom discourse as it affects reading comprehension. Research in the Teaching of English, 40(4), 392–412.

- Palinscar, A. S. & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1(2), 117–175. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci0102_1

- Puzio, K. & Colby, G. T. (2013). Cooperative learning and literacy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 6(4), 339–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2013.775683

- Rydland, V. & Grover, V. (2019). Argumentative peer discussions following individual reading increase comprehension. Language and Education, 33(4), 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2018.1545786

- Stevens, R., Slavin, R. & Farnish, A. (1991). The effects of cooperative learning and direct instruction in reading-comprehension strategies on main idea identification. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.83.1.8

- Wells, G. (1999). Using the tool-kit of discourse in the activity of learning and teaching (pp. 231–266). Cambridge Books Online.

- Wilkinson, I. A. G., & Son, E. H. (2011). A dialogic turn in research on learning and teaching to comprehend. In M. L. Kamil, P. D. Pearson, M. E. Birr, P. Afflerbach, & P. B. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of reading research, volume IV. Routledge.

- Zapata, A., Sánchez, L., & Robinson, A. (2018). Examining young children’s envisionment building responses to postmodern picturebooks. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 18(4), 439–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798416674253