Background

The ability to write is essential to being able to participate in society. Most children learn to write and communicate through writing at school; however, communicating through writing is challenging for some. One group that struggles with writing is children who have been diagnosed with dyslexia. Dyslexia is characterized by difficulties in reading and writing. The main challenge is related to decoding when reading (Snowling & Hulme, 2012) and difficulties with spelling when writing (Rice, 2004).

Students with dyslexia make many spelling mistakes when writing (Rice, 2004). Most spelling errors can be easily corrected by spell checkers; however, students who struggle with spelling do not only make more spelling errors than other students, they also write more slowly and hesitate more in front of words and in the middle of words while they write (Torrance et al, 2016; Wengelin, 2007). This slow writing, typical of children with dyslexia, is related to spelling ability (Sumner et al., 2013). Thus, because of their difficulties with spelling, writing can be resource-demanding and hard work for students with dyslexia. Furthermore, research has shown that struggling with spelling seems to be related to poor overall text quality for writers with dyslexia (e.g., Berninger et al., 2008; Connelly et al., 2006; Tops et al., 2013; Torrance et al., 2016). It is possible that hesitation and uncertainty associated with spelling are responsible for disturbing other processes students with writing difficulties often struggle with, like planning, composing, and revising texts (Hebert et al., 2018; Mason et al., 2011). In addition to their spelling difficulties, students with dyslexia struggle to read what they have written (Hebert et al., 2018).

By using assistive technology, students with writing difficulties such as dyslexia are better able to produce text (cf. Arcon et al., 2017; Perelmutter et al., 2017; Svensson & Lindeblad, 2019). Students with writing difficulties can learn to use speech-to-text programs instead of writing text by hand or keyboard. When using speech-to-text programs, the transcription part of the text production process radically changes from encoding and typing to speaking. This means that when students speak their texts, the demands of spelling are removed, possibly enabling students to focus more on other aspects of text production. There is, however, the possibility that the technology and use of speech to produce text may demand attention to other aspects that may require further scrutiny. To date, there is little knowledge about how interventions focusing on using speech-to-text might influence texts written by students with dyslexia and, furthermore, knowledge about what their production process might look like. The present study protocol describes a study designed to address this research gap by examining the impact on students’ texts of an intervention focusing on using speech-to-text and further investigating the writing process when students with dyslexia use speech-to-text technology. Students will use a speech recognition program in combination with a text-to-speech program (speech synthesizer).

According to the simple view of writing (Berninger, 2000; Berninger et al., 1996, 2002), transcription2 (spelling, handwriting, and keyboarding) is a component that works together with executive functions (planning, composing, and reviewing the text) for the goal of text generation (generating ideas and translating those ideas into language) in working memory. These three components of the writing process both cooperate to create a text and compete for the limited resources in working memory (Berninger & Amtmann, 2003). Because spelling is a problem for students with dyslexia, transcription will demand much of the limited resources in working memory when writing, leaving few resources for other components. This may result in a text with lower quality (Berninger & Amtmann, 2003). When changing the transcription process from producing written letters using correct orthography to producing spoken words, there will be a change in transcription conditions that may reduce the burden on working memory. By removing the demands from spelling, it is possible that resources are freed, making it possible for the writer to concentrate more on text generation. This may increase text quality (Berninger & Amtmann, 2003), unless the use of speech-to-text creates new obstacles. When dictating, the students must adapt the spoken language to the conventions and style of the written language and must speak clearly and distinctly because, otherwise, the speech-to-text program may fail to recognize speech correctly (Kraft et al., 2019), resulting in producing words other than those intended.

Another model that may frame our study is Hayes and Berninger’s (2014) model for cognitive processes in writing. This model has three levels: resource, process, and control. At the process level in the model, transcribing technology is an interacting resource. When changing transcribing technology from handwriting or keyboarding to text generation through spoken input, not only will the role of the transcriber be radically changed but other parts of the writing process resources will also be affected. The most striking change when speaking text is that the move from the translator to the transcriber is a fast auditive or internal action, instead of a slower physical transcription. In addition, writers who struggle with spelling must occupy the evaluator by the spelling of words, but when speaking text, there is the possibility to propose longer text bursts orally (Torrance, 2015), which gives the evaluator tasks at the sentence level rather than the word level, controlling the quality of each spoken sentence rather than checking if the spelling is correct. At the resource level, all interacting resources mentioned in the Hayes and Berninger model (2014) may be affected when students with dyslexia learn to use new technology for text production. Both attention and working memory probably change the mode from purely visual to audiovisual text production. The use of new technology may also require attention in itself, such as turning it on and off or switching from speech-to-text to text-to-speech. By using text-to-speech instead of decoding (reading) the produced text, the reading resource will also be affected differently. In addition, long-term memory will no longer be “asked” for the correct spelling of words and may be released for other tasks at a higher text level.

Assistive technologies, such as text-to-speech, can also compensate for reading difficulties during revision. Instead of reading what they have written, students with dyslexia can be taught to use text-to-speech (Nordström et al., 2019; Perelmutter et al., 2017; Svensson et al., 2021). When a student with dyslexia can listen to the produced text instead of decoding it, the capacity of the working memory is relieved (cf., Hebert et al., 2018).

However, mastering assistive technologies can be challenging. Students with writing difficulties must receive individualized support to increase their ability to use a speech-to-text program and other assistive technologies such as spell checkers and word prediction for text production (Svendsen, 2016, Svensson et al., 2021).

Study plan

Aim and research questions

In the study described here, we attempt to answer the following questions:

1) What is the impact of an intervention focusing on using speech-to-text on texts written by 10–12-year-old students with dyslexia, in terms of textual attributes such as length, lexical range, and accuracy?

2) What characterizes the writing process when students with dyslexia aged 10–12 use speech-to-text to produce narrative texts?

Method

Participants

Fifteen students aged 10–12 (five from each country: Denmark [DK], Norway [NO], and Sweden [SE]) will be recruited by researchers through special educators and principals. We will target students with severe reading and writing difficulties or a dyslexia diagnosis (Rose, 2009). The selection criteria for students participating in the study are as follows:

- Have written language difficulties as the primary difficulty

- Have attended all school years in a DK/NO/SE school

- Have phonological difficulties or a dyslexia diagnosis

To avoid false positives, the students must be one standard deviation below the mean on the following screening tests at their schools: (1) non-word reading; and (2) sight word reading (DK: Elbros ordlister https://laes.hum.ku.dk/test/ NO: Logos, Logometrica, https://logometrica.no/, SE: Elwér et al., 2016). In addition, they must have a school history of writing difficulties, as verified by their teachers prior to the intervention.

Baseline measures and background

Baseline measures will be collected prior to the intervention. Researchers will conduct individual assessments of all students. Students’ spelling ability will be tested by national tests: in DK, Møller and Juul (2017); in NO, Skaathun (2018); and in SE, Elwér et al. (2016). In addition, information about the students’ age, gender, and previous use of technological tools will be collected. The spelling tests will be repeated after the intervention to obtain information about the possible development of spelling throughout the intervention period.

Data collection and analyses

Next, we will describe the applied methods for the two studies: (1) a quantitative study of the development of textual attributes, such as length, lexical range, and accuracy using speech-to-text technology, and (2) a qualitative study of the writing process when using speech-to-text for text production.

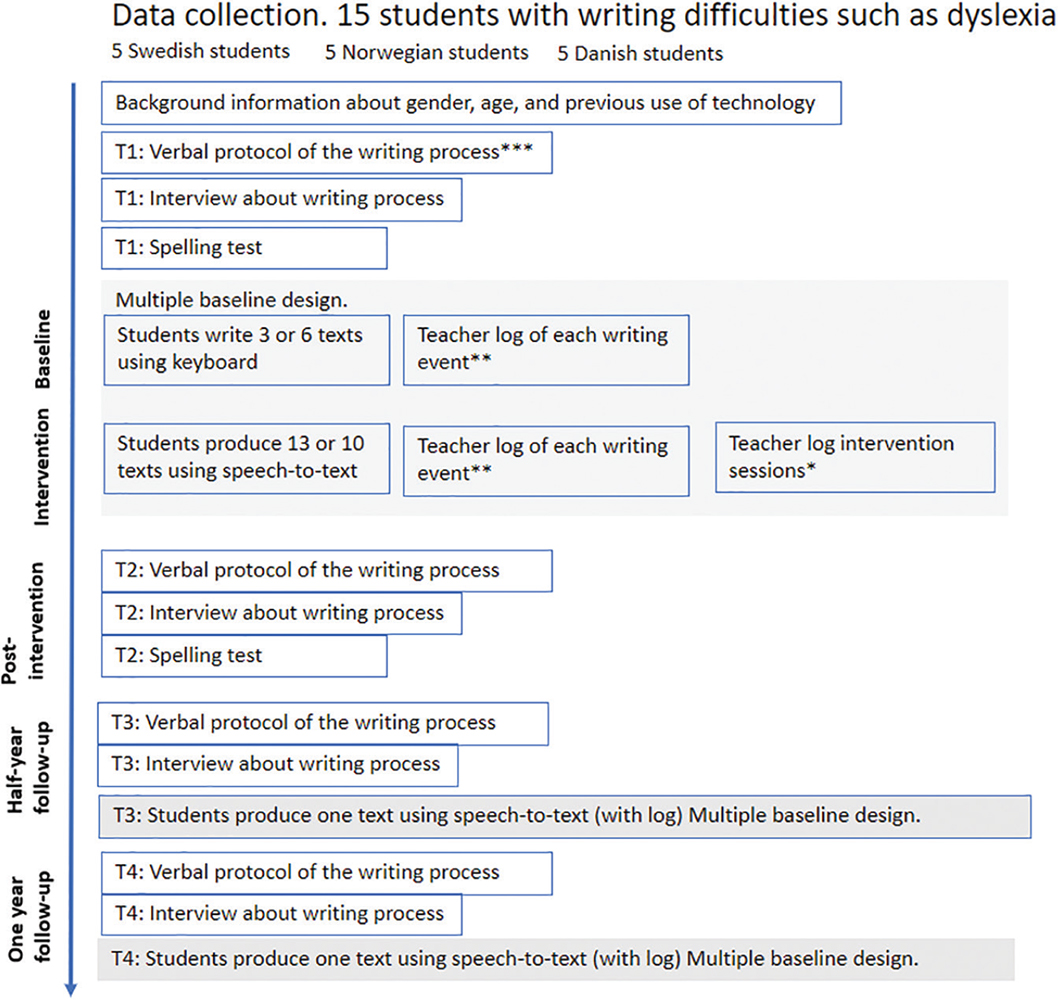

Figure 1. Data collected in the two studies

* The teachers will log the duration of the session, deviations from the teacher guide, which technology is being used and how speech-to-text technology is being used, the students’ handling of the technology (independently or otherwise), inhibiting and promoting factors for their text production, concentration and attention to the task, and experiences and views on producing text with speech-to-text technology.

** Logs concerning which technology and AT are used on the test occasions.

*** For Study 2 (verbal protocols), the texts produced are available.

Study 1

Study 1 will use a multiple baseline, single-case design (Kratochwill et al., 2010; Riley-Tillman et al., 2020). The benefit of such a design is that it can follow each student more carefully. In addition, instead of many participants, the design implies an increased number of test occasions. Thus, it is possible to conduct individual analyses instead of a mean result for a group that can hide non-responders. Moreover, with a multiple baseline single-case design, the individual becomes their own control, and data will be collected continuously: pre-intervention, intermediate, and post-intervention, with active manipulation of the independent variable (speech-to-text) (Bouwmeester & Jongerling, 2020; Kazdin, 2021; Kratochwill et al., 2010). As the study will be conducted in three Nordic countries, there will be three different languages and speech-to-text programs that might influence the outcome of the intervention. However, as the programs have the same functions and the test measures the same linguistic skills regardless of the language, we think it is possible to discuss students’ progress irrespective of language. It is also possible to examine in more detail the outcomes among students with respect to their different languages and applied speech-to-text programs.

In the first stage of Study 1 (the baseline period), students will type on a keyboard. This is a pre-intervention period, where the number of measurements will vary between participants, but there will be at least three (Kratochwill et al., 2010), and the aim is to reach the stability of the behavior before the intervention is implemented (Auerbach & Zeitlin, 2022; Kazdin, 2021) and to reduce the risk of threats to internal validity due to maturity or external events (Bouwmeester & Jongerling, 2020). During the second stage (the intervention period), the students will produce text using speech-to-text and text-to-speech in text revision. Depending on the number of test occasions the students have during the baseline, they will be monitored on 10 or 13 test occasions during the intervention, and two follow-up occasions. Their ability to produce text will be measured 18 times each. The test will consist of students producing a narrative text using speech-to-text (or keyboard at baseline) for 10 minutes using an illustration of an everyday event as a prompt. Short narratives supported by pictures are chosen because we think they demand low cognitive resources—cognitive resources that may be devoted to the use of technology. To reduce the possible systematic effect of the pictures, the presentation of the different pictures is randomized using a test form made for each student in advance.

The students’ texts produced during baseline, intervention, and follow-ups will be evaluated with an instrument measuring text quality primarily at the word level, including five measures as follows: the number of words / text length (Hosp et al., 2016), word diversity / number of unique words (Olinghouse & Graham, 2009), word length (words with seven letters or more) (Higgins & Raskind, 1995), number of correct words (Hosp et al., 2016), and number of correct word sequences (CWS), which is a measure of word pairs correctly spelled and acceptable within the context of the phrase (Hosp et al., 2016). These measures will be sensitive to changes and easy to conduct to ensure high intercoder reliability among researchers. Therefore, all texts will be scored by researchers who speak the same native language as the students.

In addition, each intervention session and test occasion will be documented by teachers’ written logs to provide information about the implementation of the intervention and maintain fidelity. Finally, the results will be presented with a visual analysis to show, for example, the trend, stability, and level of the ability to produce text. Moreover, effect analyses with non-overlapping methods will be used (Riley-Tillman et al., 2020).

Study 2

This study aims to investigate the writing process when students aged 10–12 with dyslexia use speech-to-text to produce narrative text. To investigate this, verbal protocols are used as a data collection method, which has the potential to investigate cognitive processes during text production, and to identify specific writing strategies (Hayes & Flower, 1980; Janssen et al., 1996; Tillema et al., 2011) and strategies for text production using assistive technology (Svendsen, 2016). When participants produce text orally by dictating it directly into a computer document, the method must be adapted to that writing situation. Therefore, we find it necessary to record the students’ speech, the sound from the computer, and the researchers’ voices simultaneously, with the incoming text being displayed on the computer screen. This is done by: (1) recording screencasts with sound; and (2) an external camera monitoring the students’ actions from behind, which may capture actions that are not caught by the screencast and also ensure that we have extra footage in case we run into technical problems with the screencasts, a highly likely scenario. In summary, the data in this study will record screencasts and videos (both with sound) of participants’ text production when using speech-to-text. This specific data collection method has been piloted in a previous study by Svendsen (2016). Data will be collected four times: at pre and post-intervention, and follow-ups after six and twelve months, in all countries.

On each data collection occasion, the participants will be asked to complete the same type of writing task. They must produce narrative texts based on a comic strip with a missing panel (see Fig. 2).

These strips shall support the students with content and text structure, leaving as much cognitive attention as possible to text generation, technology, and the thinking-aloud process. We assume that the thinking-aloud process may disturb text production; thus, the quality of the text written during the video recording will not be evaluated, and consequently, the elicitation material in this study is not randomized.

At each text production stage, the students will be instructed to think aloud, as recommended by Ericsson and Simon (1984/1993), in Pressley and Afflerbach (1995). Verbal protocol recording will immediately be followed by a qualitative interview. The goal of the interview is to obtain in-depth information from the students immediately after finishing their writing tasks, for example, by asking them to elaborate on why they chose to delete text chunks or what they were thinking when the technology failed, and they had to repeat the same sentence several times. Other questions will be used for clarification, for example, asking the students to explain details about their use of the technological programs. The researcher prepares this interview by observing the students working on their writing assignments and taking observation notes along the way. The post-interview makes it possible to gain further access to the students’ thoughts during text production.

Three main problems occur when using verbal protocols: (1) epistemological problems, (2) ontological problems, and (3) language as a methodological problem (Gøttsche, 2019). An epistemological problem occurs due to uncertainty as to whether it makes sense to talk about access to internal processes that take place in the brain, “because thoughts do not have its automatic counterpart in words, the transition from thought to words leads through meaning” (Vygotsky, 1962). An ontological problem occurs because the method, which intends to investigate a natural cognitive process due to its form, comes to intervene in the same process, as the language itself can change the thought content when verbalized. Third, the language itself creates a methodological problem, which may be of the greatest concern because it is created by the individual and, thus, is interwoven with the individual’s personality, which must be interpreted by someone from another lifeworld.

Despite these fundamental methodological issues, verbal protocols are recognized for “providing a window into the cognitive and psychological processes involved in writing” (Graham et al., 2018, p. 145). In this study, the method must be used with the three fundamental problems. We accommodate the critique of verbal protocols in several ways, including interrupting participants as little as possible with prompts during text production, and waiting to ask for details until after they have completed the task. Moreover, the analyses will be largely based on screen recordings, which will provide insights into text production in relation to the participants’ use of speech-to-text. When publishing the results, we will carefully discuss how we have addressed these fundamental issues in our analyses and interpretations of the data.

The analysis framework is data-driven (Tanggaard & Brinkmann, 2010), inspired by Hayes and Berninger’s (2014) model of cognitive processes in writing and the analysis of technology-based strategies (Svendsen, 2016). The coding categories will be formed as the themes are revealed during the analysis of the hermeneutic process and will focus on the writing process. The analysis focuses on how the use of speech-to-text influences the writing process using the simple view of writing (Berninger et al., 2002) and Hayes and Berninger’s (2014) model of cognitive processes in writing as a theoretical framework for deductive coding categories. From this theoretical perspective, writing strategies are connected to planning, generating ideas, and text revision; therefore, it is possible to detect any writing strategies developed by the students, regardless of whether they have been instructed in that strategy.

A coding manual will be produced by all the coders to ensure that the coding categories are transparent. Uncertainties during the coding process will be discussed by the research team to ensure intercoder reliability. Furthermore, one screen will be double scored by two researchers. To secure an understanding of the students’ speech, the data must be scored by researchers who speak the same native language as the students.

Intervention

The intervention in the current studies is planned and organized to support skills for using speech-to-text technology for text production among students with severe dyslexia. Students learn to use speech-to-text; however, to check and revise their texts, they are also taught to listen to the texts using text-to-speech.

The intervention is based on years of experience at the Competence Center for Reading in Aarhus (kcl.aarhus.dk). The Danish intervention is part of a seven-week learning program at the Competence Center. This program has led to positive and persistent effects on “pupils’ reading scores, personality traits, and school well-being” (Nielsen, 2021, p. 129). The content of the intervention will be developed by two highly skilled and experienced special education teachers from the Competence Center in collaboration with the research group, which connects the intervention to cognitive theories of writing (Berninger et al., 2002; Hayes & Berninger, 2014). The exact intervention of 25 sessions will be carefully described in a teacher guide (see Appendix), and then tried out on the students with dyslexia in group sessions in Denmark. To ensure fidelity and consistency in implementing interventions across the three countries, Swedish and Norwegian teachers will attend a two-day training course where the intervention will be presented. The course will include information and clarification about the content of the intervention, session by session, as well as technical issues such as how to use the speech-to-text programs, the test procedure, and documentation. The intervention will be teacher-led, and 25 sessions will be distributed over seven weeks. Each session will be at least 30 minutes in length and will be offered individually to students in Norway and Sweden. In these two countries, regular meetings will be held with researchers and teachers for feedback before and during the intervention. Thus, the feedback is to maintain fidelity and ensure that the teachers understand the instructions and can clear up ambiguities and discuss possible deviations.

During the intervention, students will use the technological equipment available at their schools, such as personal computers, tablets (iPads), or Chromebooks with Google Docs, Appwriter, or IntoWords. However, the project will support students by providing a good headset with a microphone, which is not always available at schools but is decisive for the project. Speech-to-text will allow the intervention) to be adapted to the individual, following a single-case design (Kazdin, 2021) The intervention will be guided by a manual that includes a structured working process for text production.

1. Preparation:

a. Prepare the computer and the task.

b. Open an empty document and save it.

c. Check the microphone and sound.

2. Dictation:

a. Say the sentence aloud without recording it (or think the sentence).

b. Record the sentence with speech-to-text.

c. Say or type a full stop.

3. Revision:

a. Listen to the sentence with text-to-speech.

b. Assess the sentence.

c. Make necessary changes.

This structured process for producing text with speech-to-text will first be presented and modeled by the teacher (Sessions 1–6, see Appendix), and then practiced under supervision to build up the students’ confidence in using the technology (Sessions 7–14). In the final sessions, the students will be instructed to use technology independently under observation to consolidate the speech-to-text routines (Sessions 15–25). All sessions draw on Vygotsky’s (1962) scaffolding and proximal development learning theory. Progress will be evaluated by the student and teacher at regular intervals, according to descriptions in the teacher guide.

The intervention aims to teach students using speech-to-text and text-to-speech routines, which we assume are necessary to handle the speech-to-text program.

Ethics

The project is approved by NSD/Sikt, notification form 779082, and the Ethical Review Board in Sweden approved this study (reference number: Dnr 2020-05024.). Denmark has no requirement for ethical approval for research. However, the study carefully follows Danish laws and ethical guidelines for research. Thus, student participation is voluntary and can be canceled at any time without explanation. Consent for students’ participation in the research project will be obtained from their parents as the students are under 15 years of age. It will also be explained to the students verbally that participation is voluntary and that they can withdraw their consent at any time; if the intervention fails, it must either be changed (if possible) or stopped for the student who experiences failure. All analyses and the publication of data will be conducted anonymously. Data materials and results will be handled carefully and stored securely, and they will not be made available to unauthorized people.

Summary and implications

To the best of our knowledge, there is little research that examines the impact of an intervention involving text production with speech-to-text and text-to-speech programs on the quality and length of texts by students with dyslexia. In the same way, little research has been conducted on how this affects the writing process when students with dyslexia produce narrative texts with speech-to-text. Both research gaps are addressed in the current studies.

The studies may provide information about the potential for improving text quality and text length through an intensive intervention with assistive technology. They may also provide information about how students with dyslexia produce text when dictating with speech-to-text and revising with text-to-speech. Both studies can contribute to developing school practices when it comes to supporting students with considerable writing difficulties.

Personnel

Principal investigators in alphabetical order:

Gunilla Almgren Bäck, Department of Psychology, Linnaeus University, Sweden

Margunn Mossige, National Centre for Reading Education and Research, University of Stavanger, Norway

Helle Bundgaard Svendsen, VIA Research Centre for Pedagogy and Education, Denmark.

Idor Svensson, Department of Psychology, Linnaeus University, Sweden

Co-investigators in alphabetical order:

Grete Dolmer, VIA Research Centre for Pedagogy and Education, Denmark

Linda Fälth, Department of Pedagogy, Linnaeus University, Sweden

Nina Berg Gøttsche, VIA Research Centre for Pedagogy and Education, Denmark

Vibeke Rønneberg, National Centre for Reading Education and Research, University of Stavanger, Norway

Heidi Selenius, Department of Psychology, Linnaeus University; and Department of Special Education, Stockholm University, Sweden

Acknowledgment and funding

Thanks to Annemette Stoklund and Birgitte H. Bønding, Competence Center for Reading in Aarhus, Denmark, for the development of the intervention. Thanks to Eivor Finset Spilling (Spilling et al., 2022) who inspired us to use an illustration of an everyday event as a prompt for the writing tests in Study 1. Thanks to Grete Gøttsche who will participate in developing 21 different events for Study 1, and thanks to Tim Levang who will draw them. And, thanks to READ (Andersen et al., 2018) for permission to use comic strips from their project as prompts in Study 2.

The project is partly funded by Nordplus Horizontal NPHZ-2020/10030 (2020–2022) and the Promobilia Foundation, ref. 20207, in Sweden.

Appendix

Intervention Teacher Guide

References

- Andersen, S. C., Christensen, M. V., Nielsen, H. S., Thomsen, M. K., Østerbye, T., & Rowe, M. L. (2018). How reading and writing support each other across a school year in primary school children. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 55, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.09.005

- Arcon, N., Klein, P. D., & Dombroski, J. D. (2017). Effects of dictation, speech to text, and handwriting on the written composition of elementary school English language learners. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 33(6), 533–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2016.1253513

- Auerbach, C., & Zeitlin, W. (2022). SSD for R. An R package for analyzing single-subject data (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Berninger, V. W. (2000). Development of language by hand and its connections with language by ear, mouth, and eye. Topics in Language Disorders, 20(4), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/00011363-200020040-00007

- Berninger, V. W., & Amtmann, D. (2003). Preventing written expression disabilities through early and continuing assessment and intervention for handwriting and/or spelling problems: Research into practice. In H. L. Swanson, K. R. Harris, & S. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of learning disabilities, (pp. 345–363). Guilford Press.

- Berninger, V., Fuller, F., & Whitaker, D. (1996). A process model of writing development across the lifespan. Educational Psychology Review, 8, 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01464073

- Berninger, V. W., Nielsen, K. H., Abbott, R. D., Wijsman, E., & Raskind, W. (2008). Writing problems in developmental dyslexia: Under-recognized and under-treated. Journal of School Psychology, 46(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.11.008

- Berninger, V. W., Vaughan, K. B., Abbott, R. D., Begay, K. K., Coleman, K. B., Curtin, G., Hawkins, J. M., & Graham, S. (2002). Teaching spelling and composition alone and together: Implications for the simple view of writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.291

- Bouwmeester, S., & Jongerling, J. (2020). Power of a randomization test in a single case multiple baseline AB design. PloS one, 15(2), e0228355. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228355

- Connelly, V., Campbell, S., MacLean, M., & Barnes, J. (2006). Contribution of lower order skills to the written composition of college students with and without dyslexia. Developmental Neuropsychology, 29(1), 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326942dn2901_9

- Elwér, Å., Fridolfsson, I., Samuelsson, S., & Wiklund, C. (2016). LäSt. Diagnostisering av grundläggande färdigheter i läs- och stavingsförmåga hos elever i årskurs 1–6. Hogrefe. LäSt – Hogrefe.se

- Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1984/1993). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data. MIT Press. (Original work published 1983).

- Graham, S., Harris, K. R., MacArthur C., Santangelo, T. (2018). Self-regulation and writing. In D. H. Schunk & J. A. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 138–152). Routledge.

- Gøttsche, N. B. (2019). “Det var nok mit største ønske at kunne blive bedre til at læse” – et kvalitativt Verbal Protocol-studie af hvordan læseforståelsesvanskeligheder manifesterer sig i overbygningens litteraturundervisning i grundskolen [“It was probably my greatest wish to be able to read better” – a qualitative Verbal Protocol study of how reading comprehension difficulties manifest themselves in upper secondary literature teaching in primary school] [PhD thesis]. Aarhus University.

- Hayes, J. R., & Berninger, V. W. (2014). Cognitive processes in writing. In I. B. Arfe, V. W. Berninger & J. Dockrell (Eds.), Writing development in children with hearing loss, dyslexia, or oral language problems: Implications for assessment and instruction (pp. 3–15). Oxford University Press, USA.

- Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. (1980). Identifying the organization of writing processes. In L. W. Gregg & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive processes in writing: An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 3–30). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Hebert, M., Kearns, D. M., Hayes, J. B., Bazis, P., & Cooper, S. (2018). Why children with dyslexia struggle with writing and how to help them. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(4), 843–863. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_LSHSS-DYSLC-18-0024

- Higgins, E. L., & Raskind, M. H. (1995). Compensatory effectiveness of speech recognition on the written composition performance of postsecondary students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 18(2), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511202

- Hosp, M. K., Hosp, J. L., & Howell, K. W. (2016). The ABCs of CBM: A practical guide to curriculum-based measurement (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Janssen, D., van Waes, L., & van den Bergh, H. (1996). Effects of thinking aloud on writing processes. In C. M. Levy & S. Ransdell (Eds.), The science of writing: Theories, methods, individual differences, and applications (pp. 233–250). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kazdin, A. E. (2021). Research design in clinical psychology (5th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Kraft, S., Thurfjell, F., Rack, J., & Wengelin, Å. (2019). Lexikala analyser av muntlig, tangentbordsskriven och dikterad text producerad av barn med stavningssvårigheter. Nordic Journal of Literacy Research, 5(3), 102–122. https://doi.org/10.23865/njlr.v5.1511

- Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation. What Works Clearinghouse. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/docs/referenceresources/wwc_scd.pdf

- Mason, L. H., Harris, K. R., & Graham, S. (2011). Self-regulated strategy development for students with writing difficulties. Theory Into Practice, 50(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2011.534922

- Møller, L., & Juul, H. (2017). Skriftsproglig udvikling. Læse- og staveprøver til 0.-8. Klasse. Hogrefe Psykologisk forlag. https://www.hogrefe.com/dk/shop/staveprove-2-skriftsproglig-udvikling-10-stk.html

- Nielsen, S. A. (2021). Essays on educational interventions for disadvantaged children. [PhD dissertation]. Aarhus University.

- Nordström, T., Nilsson, S., Gustafson, S., & Svensson, S. (2019). Assistive technology applications for students with reading difficulties: Special education teachers’ experiences and perceptions. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 14(8), 798–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2018.1499142

- Olinghouse, N. G., & Graham, S. (2009). The relationship between the discourse knowledge and the writing performance of elementary-grade students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013462

- Perelmutter, B., McGregor, K. K., & Gordon, K. R. (2017). Assistive technology interventions for adolescents and adults with learning disabilities: An evidence-based systematic review and meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 114, 139–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.06.005

- Pressley, M. & Afflerbach, P. (1995). Verbal protocols of reading. The nature of constructively responsive reading. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Rice, M. (2004). Developmental dyslexia in adults: A research review. National Research and Development Centre for Adult Literacy and Numeracy.

- Rose, J. (Ed.). (2009). Identifying and teaching children and young people with dyslexia and literacy difficulties. An independent report by Sir Jim Rose to the Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, June 2009. DCSF Publications.

- Riley-Tillman, T. C., Burns, M. K., & Kilgus, S. P. (2020). Evaluating educational interventions: Single-case design for measuring response to intervention. Guilford Press.

- Skaathun, A. (2018). Lesesenterets staveprøve. Lesesenteret.

- Snowling, M., & Hulme, C. (2012). Annual research review: The nature and classification of reading disorders — a commentary on proposals for DSM-5. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(5), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02495

- Spilling, E. F., Rønneberg, V., Rogne, W. M., Roeser, J., & Torrance, M. (2022). Handwriting versus keyboarding: Does writing modality affect quality of narratives written by beginning writers? Reading and Writing, 35(1), 129–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10169-y

- Sumner, E., Connelly, V., & Barnett, A. L. (2013). Children with dyslexia are slow writers because they pause more often and not because they are slow at handwriting execution. Reading and Writing, 26, 991–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9403-6

- Svendsen, H. B. (2016). Anden artikel: Technology-based writing: Young writers with dyslexia using literacy technology. In H. B. Svendsen, Teknologibaseret læsning og skrivning i folkeskolen (pp. 168–188) [PhD dissertation]. Aarhus University.

- Svensson, I., & Lindeblad, E. (2019). 20 års forskning i assisterande teknik – Vad har vi lärt oss? [Assistive technology, twenty years of research – What have we learnt?]. Viden om Literacy, (26).

- Svensson, I., Nordström, T., Lindeblad, L., Gustafson, S., Björn, M., Sand, C., Almgren/Bäck, G., & Nilsson, N. (2021). Effects of assistive technology for students with reading and writing disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 16(2), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2019.1646821

- Tanggaard, S., & Brinkmann, L. (2010). Kvalitative metoder: En grundbog [Qualitative methods]. Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Tillema, M., van den Bergh, H., Rijlaarsdam, G., & Sanders, T. (2011). Relating self reports of writing behaviour and online task execution using a temporal model. Metacognition and Learning, 6, 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-011-9072-x

- Tops, W., Callens, C., van Cauwenberghe, E., Adriaens, J., & Brysbaert, M. (2013). Beyond spelling: The writing skills of students with dyslexia in higher education. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 26(5), 705–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9387-2

- Torrance, M. (2015). Understanding planning in text production. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (2nd ed., pp. 1682–1690). Guilford Press.

- Torrance, M., Rønneberg, V., Johansson, C., & Uppstad, P. H. (2016). Adolescent weak decoders writing in a shallow orthography: Process and product. Scientific Studies of Reading, 20(5), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2016.1205071

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. MIT Press.

- Wengelin, Å. (2007). The word-level focus in text production by adults with reading and writing difficulties. In M. Torrance, L. van Waes, & D. Galbraith (Eds.), Writing and cognition (pp. 67–82). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9781849508223_006

Text Performers

The intervention, freely translated from Norwegian to English.

| Week 1 | The goal of the lesson: What is the student expected to learn? | Content of the lesson: Teaching activities: What is the student expected to work on? – The student is to use speech-to-text tools each time, either in the writing test or in the exercise, or both. |

What should the teacher pay particular attention to in this lesson? |

| 1st lesson | • The student knows the goal of the speech-to-text intervention and can express this. • The student has tried out the speech-to-text function. • The student understands their issues stemming from dyslexia. • The student obtains knowledge of dyslexia in general. • The student can give examples of what issues dyslexia can cause. |

The teacher introduces the intervention. The teacher demonstrates the speech-to-text function. The student tests the speech input part of the function. Teacher and student create a mind map of issues experienced on paper or on screen. The teacher supports the writing if necessary. Materials: A template for a mind map may be used. Discuss with the student what dyslexia is, and the phonological issues it can cause. Also, discuss any other issues that might arise from these causes. |

Focus: Create a good relationship with the student. The teacher has already ensured that the computer and microphone/headset work. The teacher is attentive to whether the student succeeds in creating a text through speech. If not, the teacher must determine the cause of the issue: – Pronunciation (distinctness) – Speed – Technical issues – Timing concerning clicking the microphone and speech Remember to report on the lessons each time. |

| 2nd lesson | • The student knows how to find, start, and calibrate the speech function. • The student knows how to dictate. |

The teacher goes through digital techniques (Google Docs): – Activate the speech input function in “tools”. – Click to stop and start. |

The teacher ensures the correct language is chosen. Focus on the correct start and stop of the microphone. |

| The student explores the speech input and the text function by working with the teacher to construct sentences and then dictating them. |

The teacher focuses on acting and talking positively about the possibilities provided by the tool. The teacher pays attention to what the student does and names the actions. The teacher pays attention to the potential extent of sentences for the student. How much can the student input in one go? |

||

| Week 2 | The goal of the lesson: What is the student expected to learn? | Content of the lesson: Teaching activities: What is the student expected to work on? |

What should the teacher pay particular attention to in this lesson? |

| 3rd lesson |

• Repetition of the content in week 1 – What has been learned until now? |

Speech input in Google Docs: What do I know now? The students report what they have learned about speech-to-text routines. | Observe signs of how the student utilizes the tool. Can the student both explain and use the functions? Where do challenges arise? *Voice usage, speed, microphone, equipment, etc. |

| 4th lesson |

• Introduction to text-to-speech. • The student can listen to their text and determine if the content is clear and conveys a meaning. • Focus on the motivating factor in sharing a text. |

The student uses speech input to share a text from their close experience. Examples might be: “My morning”, “My leisure activities”, etc. The task should not be difficult content-wise, as the focus lies in practicing the routines using technology and motivation, not on the content. |

Observe how actively the student engages with the independent work. Adjust as needed. The student listens to the inputted text via the text-to-speech function, not to correct spelling errors but to focus on whether the text conveys a meaning (to preserve their motivation). The editing phase using word suggestions and spelling control in Word will be used later. |

New: The teacher introduces text-to-speech, and the student uses this to listen to their text created through speech input. |

As for spelling errors, correct endings, inserting missing words, adaptation of present/past tenses and the structure of the text – all of this will be done when the student is finished with the speech input, in order not to disturb the writing flow. | ||

| 5th lesson | Editing phase, refining the text: • Listening and correction routines; • Word suggestions and spellcheck; • Listen to the inputted text with a text-to-speech program. |

The student edits their own inputted text (from lesson 4). The student uses the word suggestion function and spellcheck to correct misspellings. Pay attention to the red lines. Afterwards, text-to-speech is used to read the text out loud: 1. One sentence at a time (the teacher assists the student in splitting the text into sentences if necessary). 2. Does the sentence convey a meaning? 3. Add punctuation and remember capitalization. |

Observe whether the student can listen through their text and have it read aloud with text-to-speech tools. Focus on reading speed, about 120 words per minute. Make adaptations for the student; some things can be difficult. |

| 6th lesson | • The listening and editing routines are repeated and the text improved. • Raising consciousness around the challenges and advantages of text-to-speech (TTS). |

Continue editing, focusing on the finished, meaningful text from lessons 4 and 5. The teacher and student discuss any challenges the student encounters with the text-to-speech routine. After this, focus on what went well. |

Celebrate the successes! |

| Week 3 | The goal of the lesson: What is the student expected to learn? | Content of the lesson: Teaching activities: What is the student expected to work on? |

What should the teacher pay particular attention to in this lesson? |

| 7th lesson |

• Further practice the TTS routine. • Listen to a text (a simple prose text) with the text-to-speech tool. • The student is to recreate the text, one sentence at a time. • Get acquainted with the split screen function. |

Preparation routines: The student prepares the computer for dictation themselves, creates a new document, activates the microphone, and checks that the sound works. Task: – The student listens to a short prose text. – Split screen: Place the prose text in one half and a new, empty document in the other. TTS routine: – The student listens to one sentence at a time, 1. retells it into the room, 2. then into a microphone, (and 3. ends sentences with a full stop). The student pays attention to their pronunciation. |

Focus on practicing the TTS routine. Independence in preparing equipment, reading, and speech input. Note any difficulties the student might have with the speech input: Dialect, voice usage, speech, microphone, equipment, etc. |

| 8th lesson |

• Practice listening and correction routines. • Use a checklist. • The student corrects any errors in sentences using re-dictation of whole sentences or with the help of spelling tools. |

Further work with the text from lesson 7. – The student finds the relevant document themselves and prepares TTS. – The student retells the text from lesson 7. – Then revision: Listen – consider. Reading speed of 120 words per minute |

Focus on independence. Consolidation of listening and correction routines. See the appended overview of the correction phase for the teacher. |

| 9th lesson |

• Practice TTS and listening and correction routine. |

Task: Engage with a text using text-to-speech and answer questions using speech-to-text. Materials: Prose text: Gjenbruk (Recycling) Questions to the prose text. |

Sentence starters from a writing template could be used. |

The student completes the entire process: Prepares – splits the screen*– listens to the text – listens to the questions – answers the questions using speech-to-text – listens and corrects (checklist). Follow the routines from lessons 7 and 5. *On the right side of the screen, the prose text to read, and on the left side, the questions where the answers can also be written. |

Focus on independent usage of the technology and usage of a TTS routine in combination with the reading and writing tools. Focus on reading comprehension, and dictation as a meaningful learning strategy for the student. |

||

| 10th lesson |

• Practice TTS in an actual task; • Using writing templates; • Learn how to edit, adjust, and insert images. |

The student now completes the first part of the process: Prepares – inserts images – produces text. Task: Independently insert images in a two-column document and dictate a short text that fits each of the images. The image and the text need to match. Topic suggestions: My family and I, my dog, my interests, etc. Materials: Poems for images (can easily be made as needed). Preparation: The student or teacher obtains the necessary images. |

Focus on motivation for using dictation. Immediately engage with issues that occur, such as wrong settings for the microphone, placement of the microphone, mumbling, and too rapid speech. Pay attention to breaks when the microphone uploads. (Red/dark color on the microphone indicates ready or not ready). |

| Week 4 | The goal of the lesson: What is the student expected to learn? | Content of the lesson: Teaching activities: What is the student expected to work on? |

What should the teacher pay particular attention to in this lesson? |

| 11th lesson |

• Practice individual listening and correction routines. • Focus on the finished text. |

The student revises the text from lesson 10: Checklist: Listen to one sentence at a time; Low speed; Does the text carry a meaning; do images and texts fit together? Then, according to what the student is ready for: Correct any spelling errors, add any words that might be missing, look at the form and endings of the words, make improvements, and use the teacher’s response to improve the text. |

Focus on the learning response in the student’s text/process. Can you discuss this further, in more detail? Assist in adding variety to the text. Focus on spoken language versus written language – What is needed in a text for a reader to understand it? Focus on motivation. |

| 12th lesson |

• The student can discuss how they produce a text via speech. • The student can describe how they revise (correct) a text using text-to-speech. • The student evaluates their texts. • Motivation and monitoring/reflection over their text. • Teacher response to the text and working routines. |

Teacher and student discuss the work process: Producing a text and revising a text. The teacher gives feedback on the routines used and asks how the student sees them. Summary: What works well, and what needs more work? Discuss the results (the text): The student evaluates their texts, and the teacher gives feedback. Considerable time may be spent on this. Discuss the next steps: Formulate a goal for the next step. |

Focus on the student’s ability to engage with the content of the task. Be aware during the response: There may be suggestions for improving the text, but also the acknowledgment of good work. For instance: The image and the text go well together, the text is well-told, you could possibly tell more, you are good at using different words in your sentences, you have used the checklist, capitalization is correct, numbering is used, and so on. |

| 13th lesson | Consolidation: The student uses writing templates and practices listening and correction routines. | Continue writing the text for images, the entire process: Preparation, speech input, revision. Work within the writing template (two-column note from lesson 10). The teacher gives feedback on the process. |

Focus on motivation, mastery, and increased confidence in their mastery. |

| 14th lesson | Repetition and practice in TTS routines, and little evaluation. | The work continues. Which challenges do I meet using TTS? What is working well, and when does it work well? |

Focus: The student monitors and reflects on their routines. “What works for me and why?” |

| Week 5 | The goal of the lesson: What is the student expected to learn? | Content of the lesson: Teaching activities: What is the student expected to work on? |

What should the teacher pay particular attention to in this lesson? |

| 15th lesson |

• The student knows how to use TTS in the classroom. • Work with the split screen. |

Preparation: The student brings a writing task from class, and the teacher and the student discuss how to complete it. The teacher helps to plan the task for the student, and helps the student if necessary: Split screen; Text on one side, question and/or writing template on the other in a table made by the student. The student listens to the text and inputs answers they have learned (follow the routines of preparation – speech input – revision). The teacher discusses with the student how to use TTS within the classroom. What is needed for using it in an everyday context? Make a “wish list” for the learning environment. Materials: Wishes for the environment – can also be made yourself. |

The teacher has already discussed a suitable task with the student’s regular teacher (e.g. a text with questions to answer). The teacher emphasizes the fact that TTS should be used in a class context so that the student can participate equally in the learning process. Wishes are passed on to the regular teachers and discussed with them. |

| 16th lesson |

• The student can use speech input for sentences, as well as use listening and correction routines. |

The student inputs a personal characteristic: – The student listens to a short text. – The student inputs 5–10 sentences about the person. – The student uses listening and correction routines. |

The teacher supports the student in expanding sentences and using varied language. |

| 17th lesson |

• The student can use full stops and possibly also commas competently. |

– Continue with the text from lesson 16. – The student works on routines about punctuation in the personal characteristics. o Full stop at the end of speech input; o Comma? – The student places punctuation in their text. |

The teacher is conscious of whether the student can place commas correctly; otherwise the focus is primarily on the use of full stops. |

| 18th lesson |

• The student works on learned routines. • Repetition. |

The student works within a writing template with collaboration. Continuation of the story of Stodder. Use the routines: Preparation – speech input – revision. Evaluation of the week: What have we worked on? What went well? |

Focus on a feeling of mastery for the student. |

| Week 6 | The goal of the lesson: What is the student expected to learn? | Content of the lesson: Teaching activities: What is the student expected to work on? |

What should the teacher pay particular attention to in this lesson? |

| 19th lesson |

• The student can use speech input to prepare independently for creating a text. • The student can input a narrative text with a structure. • The student is conscious of how they can introduce language variation |

This week the student will produce a fairy tale. Different parts of the text focus on the different lessons. Discussion about narrative texts and the construction of a text. Start – middle – end. Presentation of preparative work for a fairy tale. |

The teacher writes down genre characteristics, which are available to the student during the writing process. The teacher is conscious of whether the student can “imagine”. |

The student comes up with characters, times, and places, and inputs text into the fairy tale template. Discussion on: What does a good introduction contain? The teacher and the student discuss adjectives. The student works on inputting the introduction to a fairy tale, with a presentation of characters, time, and place. The student further inputs (in the following lessons) a fairy tale with a focus on descriptive words/adjectives. |

The teacher should be very supportive in the process this week. The teacher supports the use of descriptive words/adjectives. Create a collaborative list yourselves or use the one prepared for you. The teacher supports the student’s routines in the writing process by continuously naming what the student is doing. |

||

| 20th lesson |

• As above |

The student works with the middle of the fairy tale. Description of the problem. The teacher supports the student in placing full stops at the end of an inputted sentence. |

Ensure that the student is motivated for text creation. If the work stops, what is the problem? E.g. speech input, ability to come up with a text. |

| 21st lesson |

• As above |

Further work on the fairy tale. The teacher gives support where needed and gives positive feedback on routines. | Ensure that the student is motivated for text creation. If the work stops, what is the problem? E.g. speech input, ability to come up with a text. |

| 22nd lesson |

• Consolidation of material from week 6. |

Discuss what a good ending contains. – The student works on inputting the ending of the fairy tale. Evaluation: What have we worked on? What went well? |

The teacher points out when the student uses language variation, punctuation, and so on. The teacher ensures the student uses their preparation work. Focus on the student being able to express what they have learned. |

|

– Variation in language; – Sentence starters (in writing template); – Punctuation and capitalization; – Listening and correction routines (use the checklist). |

|||

| Week 7 | The goal of the lesson: What is the student expected to learn? | Content of the lesson: Teaching activities: What is the student expected to work on? |

What should the teacher pay particular attention to in this lesson? |

| 23rd lesson |

• The student gains an overview of what has been dealt with in the intervention. |

Teacher and student create a mind map together that covers the work done over the previous 6 weeks: • Programs • Routines • Task type |

The teacher helps the student to express “why” the work has been done on TTS and other strategies. Focus on the student gaining an overview of “what” and “why”. |

| 24th lesson |

• The student gains insight into what they have learned. |

The student expresses what opportunities TTS gives them. The student creates a document (column notes?) where they use speech input to create a text on what they have learned. Follow the routines: Preparations – speech input – revision. Observe the routine for adding punctuation. |

The teacher emphasizes the fact that the student’s text will be passed on to their regular teacher, to gain an insight into what the student has learned. |

| 25th lesson |

• The student is made conscious of their text production process and the use of routines. • The student can show examples of how they have developed their texts during the practice period. • The student can describe what has been made easier for them during the text production process. |

The student fills out “My work plan” together with the teacher, using speech-to-text. Finishing the intervention: Did we reach the goals? What are the next steps? Teacher and student go over the mind map from week 1, lesson 1. Has anything become easier? |

The teacher supports the student so that they remember all focus points and routines. The teacher can show a student text produced at the beginning of the period and a completed product. Teacher and student together can focus on everything that the student has learned. Will the student have a future goal? |