Introduction

Immigrants who arrive in a new country need to develop skills in the dominant language. In Sweden, language education for adults is offered through Swedish for Immigrants (SFI), language classes that are free of charge and organised at a municipal level. For immigrants who have never had the opportunity to develop more than limited literacy skills, learning a new language involves developing basic literacy skills. In SFI, adults with no more than four years of formal education before arrival in Sweden are referred to study path 1. We direct our interest towards literacy education in study path 1. Students start with course A before continuing to courses B, C, and D, which ends with a final national test. Existing research in Sweden on emergent literacy among adults is fragmented and seldom has a focus on teaching (Lundgren et al., 2017).

There are growing demands for the rapid development of Swedish skills for students in SFI, with particular concerns being expressed about students in study path 1, who are often perceived as developing too slowly (SOU 2020:66). Investigating the quality of this literacy education, and particularly the teachers who deliver it, is thus highly relevant. SFI teachers are required to have a teaching qualification with at least 30 ECTS in Swedish as an L2. However, there are no requirements when it comes to a qualification in teaching literacy. In Sweden, teacher training in literacy generally focuses on early literacy education for children in their first language (L1), and not on adult L2 learners (Colliander, 2018; Fejes, 2019).

Research on the development of basic literacy skills among adults draws mainly on experiences in developing countries (e.g. Kerfoot, 2009) and education in the form of literacy programmes, often called alphabetisation programmes (Wedin, 2007) or literacy practices in everyday settings (Norlund Shaswar, 2014; Prinsloo & Breier, 1996; Street, 1984). Research focusing on literacy education for adult L2 learners includes studies from Sweden (Wedin & Norlund Shaswar, 2019, 2021), Finland (Malessa, 2018), Timor (Rashid, 2020), and Nepal (Singh & Sherchan, 2019) as well as Luxembourg, Canada, and Belgium (Choi & Ziegler, 2015). Wedin et al. (2016, 2018) have focused on classroom interaction and students’ everyday literacy practices. Singh and Sherchan (2019) as well as Rashid (2020) showed the importance of literacy programmes which value participants’ earlier experiences. This was also highlighted by Lewis and Bigelow (2019), who argued for the need for educators (and researchers) to examine their own expectations and preconceptions.

Hornberger and Skilton-Sylvester (2000) argued for the importance of assisting learners in the development of literacy skills in their L1 as well as in their L2 (see also Haznedar et al., 2018; Young-Scholten, 2015). There is, however, little research on the teaching of emergent and basic literacy in formal education for adult L2 students, particularly on the teaching and learning of letters.

To develop our understanding of current approaches to reading and writing instruction for adult L2 learners, we aimed to examine teacher perceptions of letter learning in SFI, as demonstrated in their teaching. Although we recognise the importance of acquiring a range of literacy skills as part of language acquisition generally, the focus here is on letter learning as one important aspect of basic literacy education. This study is part of a larger project entitled Literacy education at a basic level in Swedish for immigrants.1

Theoretical frame and research overview

The theoretical frame for this study is taken from New Literacy Studies (Barton, 2007; Street, 1995, 2009), in which literacy is perceived as socially shared and organised. This means that literacy is not understood to be a set of autonomous skills that are fixed, universal, or given, as presumed in earlier research and popular discourse (e.g. Goody, 1982) – what Street calls an autonomous view of literacy; rather, it is understood to be constructed through what he calls an ideological view, which emphasises not only the situatedness of literacy but also the multiple nature of literacy practices. Thus, literacy in this case is understood to be an inseparable part of students’ L2 acquisition. The frame of New Literacy Studies means that the study has a sociocultural base and implies that teachers’ perceptions are understood through their teaching practices, which are socially, culturally, and historically situated. The situatedness of literacy practices relates closely to an understanding of oral and written language use as taking place through the participants’ creation of meaning making. Thus, language is understood as being crucial for the negotiation of meaning that takes place in a classroom.

Developing emergent and basic literacy

One important aspect of acquiring basic literacy is the experience of using script. Students in SFI have varied backgrounds in the form of knowledge and experiences in relation to literacy in general and their knowledge of alphabetic script specifically. In study path 1, where students have little or no previous education, this is very much the case. In research that starts out from an ideological model of literacy, the importance of learners’ previous and out-of-school experiences of literacy is underlined (Street, 2009). In accordance with this perspective on literacy, letter learning in basic literacy education for adults needs to take place in relation to meaningful socially and culturally based literacy practices where learners read and write. Most of these learners are likely to have encountered written language in various forms and to have developed literacy practices in different ways. One way to understand their existing literacy ability is to assess whether they can read and write at a basic level using: (1) a Latin-based alphabet, (2) another alphabet, (3) a syllable-based script, or (4) a word-based script. This knowledge is important for teachers to plan their teaching based on relevant topics for individual students.

Because of our interest in letter learning, students’ previous experiences with alphabetic scripts, such as Latin, Arabic, Thai, or Urdu, are particularly relevant. Exposure to these scripts means that students have developed some experience with the relationship between single sounds and letters. However, as phonemes and pronunciation patterns differ between languages, for them to learn Swedish, students need to learn the Swedish phonological system, alongside other literacy skills. The Swedish vowel system is particularly rich, with nine distinct vowels, each with short and long allophones, and several allophones in standard pronunciation that are closely related to prosodic structure (see, for example, Bannert, 2004; Rosenqvist, 2007; Thorén, 2008). Prosody carries significant meaning in Swedish, and prosodic features such as stress, quantity, and tonal accent are in general difficult for L2 learners of Swedish. Thorén (2008) particularly stresses the importance of what he calls basic prosody in the L2 acquisition of Swedish. Consequently, SFI teachers need both high phonetic and phonological competence, particularly those teaching emergent literacy on study path 1. However, a study by Zetterholm (2017) indicates that for many SFI teachers, pronunciation knowledge was not included in their teacher training.

Grigonyte and Hammarberg (2014) have shown that there is a strong relationship between incorrect pronunciation and spelling mistakes for adult L2 learners. According to our own experiences as teachers, teacher educators, and researchers, traditional literacy teaching for children in the early years usually focuses on features such as vowel length at a word level, while prosodic features at a phrase and sentence level are usually disregarded (Hennius et al., 2016). Examples of such features are the difference in pronunciation of det (it), är (is) and en (a) as single words and in a sentence like “Det är en katt på stolen” (There’s a cat on the chair), which may be pronounced /deῃkat pɔstu:lən/, with det, är and en merged to /deῃ/.

In Sweden, the teaching of vowels is often treated in relation to spelling rules, and not in relation to pronunciation. For example, the letters <e>, <i>, <y>, <ä>, and <ö> are commonly called ‘soft vowels’ and are often illustrated in textbooks and by teachers using pictures of clouds. The letters <a>, <o>, <u>, and <å> are commonly called ‘hard vowels’ and are often illustrated by a stone or rock. Phonetically, these letters would be distinguished as front and back vowels. This then relates to the spelling of /ɕ/, /ʃ/ and /j/. Commonly, little focus is placed on the qualitative difference between short and long vowel phonemes or the difference in lip-rounding between vowels, such as <i>/<y> and <e>/<ö> – features that are important for L2 learners and that correspond with spelling. Nor is the common variation in vowel phonemes in relation to prosody or assimilation patterns mentioned, such as the difference in how the letter <e> is pronounced in ekollon and hunden ([eː] and [ə] respectively) and the <n> in min stol, min katt and min bil ([n], [ŋ] and [m] respectively). All these features are important for the L2 learner for effective oral and written language production.

The order in which letters are presented by teachers in early literacy education can follow various principles. Some letters may be perceived as easier to learn and thus be chosen first. Letters representing sounds that are often difficult for many L2 learners to pronounce, such as the rounded sound corresponding to the letters <y>, <u>, and <ö>, may be perceived as more difficult and thus presented after other letters with easier sound representations. Frequency may be another reason to choose some letters, such as the earlier introduction of the high frequent <e>, <a>, <s>, and <m> before the less frequent <y>, <q>, <x>, and <z>. Some letters may be perceived as less important because they do not represent their own sound. The letter <c>, for example, is pronounced as /s/ (cirkus) or /k/ (curry); <z> is pronounced as /s/ (zebra); and <q> is pronounced as /k/ but rarely used in standard spelling. The letter <x> can be perceived as more difficult because it represents two sounds in speech, /k/ and /s/ (text). Letters that are rarer in other languages, such as <å>, <ä>, and <ö>, can be perceived as more difficult, as well as letters with a pronunciation in Swedish that differs from most languages, such as <o>, <u>, <j>, and <y>. The richness of the Swedish vowel system itself can be perceived as difficult. The impression of difficulty is conveyed by the similarity between some graphemes, such as the letters b/d/q/p and f/t, and the fact that some letters have elements that need to go ‘below the line,’ such as <g>, <j>, <p>, and <y>, while others have elements that need to stretch upwards, such as <f>, <l>, and <k>, or stretch upwards at different heights, such as <t>. In addition, <g> may be perceived as difficult because it is written as <g> in handwriting but as <g> in print, much like /a/, which is often handwritten as <a> but printed as <a>.

It is a challenge for adult L2 learners to develop basic literacy skills in a language with a complex phonological system, distinctive pronunciation, and where temporal prosody is important for intelligibility. Having teachers who are competent in basic literacy teaching is thus essential for their future language success.

Early development of literacy skills among adults

The use of a socio-cultural perspective in classroom learning as the foundation is particularly relevant for SFI and study path 1 learners. Adult students at this level need to use written Swedish before they have developed such skills. For adult L2 learners, content can be said to precede technical ability; in other words, they need to use literacy while they develop literacy skills. Skills in a new language are often key to work and social integration (see, for example, Bialystok, 2001). A focus on functional skills, and on what Street (1984) called “an ideological view” rather than on a cognitive skills-based view, has been recommended by researchers such as Hornberger and Skilton-Sylvester (2000), Young-Scholten (2015), Haznedar et al. (2018) and Lewis and Bigelow (2019). The achievement of functional ability in SFI is also stipulated in the Swedish Education Act (SFS 2010:800, changed 2021:452. ch. 20, 2§) and in official documents (SKOLFS, 2017:91; SOU 2013:76).

Traditions of early literacy education in Sweden

As the requirements for teachers in SFI do not generally include training in early literacy education, it is relevant to relate the study to other educational traditions that these teachers may draw on. Sweden has a long tradition of literacy teaching and learning. In the late sixteenth century, the ability to read the catechism was considered an important skill. It was first taught by priests and parish clerks and later by the male head of the household (Johansson 1988, 1989; Lindmark, 2004; Wedin, 2010). As such, for over 400 years, Swedish citizens can be seen not only to have been literate (Isling, 1991), but also to have developed practices for teaching literacy. Compulsory primary education was introduced in Sweden in 1842, but since pupils were expected to have acquired basic reading and writing skills at home, teaching in basic literacy and numeracy was not introduced until the creation of the first two years of primary school as a distinct level (småskolan) in 1858–1882. Literacy teaching focused on phonics and started by encouraging children first to relate single letters to sounds, and then to identify one-syllable words with the consonant-vowel structure CV, VC, or CVC. In the 1970s, and under the influence of Anglo-Saxon teaching methods commonly known as whole language, the Swedish educationalist Ulrica Leimar developed Läsning på talets grund (LTG, Reading on the Basis of Speech) (Leimar, 1976). While this teaching approach became popular among some teachers, others stuck to traditional phonics. At the same time, the Witting Method (Wittingmetoden) (Witting, 1974) was developed to support students who had failed to learn how to read. The Witting Method was highly focused on phonics, with the ‘technical’ part – that is to say, coding and decoding script – separated from meaning. Taken together, phonics and Witting may be compared to what Street calls an ‘autonomic’ perspective, while whole language and LTG are examples of Street’s ‘ideological’ perspective on literacy learning. As an answer to the debate on the teaching of emergent literacy in Sweden, Liberg (1990) concluded that early reading and writing among children involves both synthetic and analytic cognitive processes. In this article, we use ‘ideological’ and ‘autonomous’ as taken from Street (1995) to represent these two broad approaches to literacy teaching.

Traditionally, when the alphabet is taught in the early years of Swedish primary school, regardless of the teacher’s methodological perspective, the approach usually involves linking each letter to its sound, its name, and the ability to write the letter. Attention is directed towards the construction of each letter and the order and direction each stroke should take, with the goal that children should develop the ability to link these letter forms together in cursive handwriting.

Since the two relatively opposed ideological and autonomous teaching approaches operate in parallel in the Swedish school system, and since both have been taught for relatively long periods, it is interesting to see to what extent traces of them appear in the teaching of emergent literacy by SFI teachers when teaching letters. To learn more about this issue, we used the following research questions to guide the analysis:

1) What perceptions of literacy teaching and learning may be understood from teachers’ presentation of letters to SFI literacy students?

2) How does the teaching of letters relate to pronunciation?

3) How are letters presented orthographically in teaching?

Methods and material

This research is part of a larger project, the aim of which is to develop basic literacy education for SFI study path 1 learners. The methodology is a combination of action research (Zeichner, 2001) and linguistic ethnography (Copland & Creese, 2015). In four schools, over a period of one and a half years, a total of 217 hours of SFI study path 1 teaching were observed. Data was collected in the form of field notes, photographs, and audio and video recordings. At two of the project schools, an initial ‘alpha group’ was set up to precede SFI course A that was intended for those who were perceived to have the lowest literacy skills when they joined the programme. The data, therefore, includes observations from two of these alpha groups as well as from courses A, B, and C from three of the participating schools. At the fourth school, observations had another focus and no observations of relevance for this study were made.

To understand teachers’ perceptions of letter learning, we identified the occasions where teachers explicitly focused on the relationship between a letter and a phoneme. On a total of 28 different occasions, we observed teachers addressing the issue of letters and the coding and decoding of letters with their students (see Table 1).

| School | Alpha-group | Course A | Course B | Course C | Number of teachers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The River | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| The Hill | 5 | 2 | 3 | ||

| The Ridge | 5 | 3 | 2 |

These occasions varied in length from a few seconds to 90 minutes. Of the total number of 217 observed hours, these occasions amounted to about 15 hours and thus only constitute a restricted part. This indicates that while letter teaching takes place in these courses, it constitutes only a small part of the curriculum and is more frequent in the alpha groups. Explicit letter presentation was only observed in the alpha group at one school, and the material does not allow comparisons between different teachers or courses. The teachers all had a teacher exam, but their education in Swedish as a second language varied between 0 to 90 ECTS. Teacher training in Swedish as a second language may, but usually does not, include literacy education at basic levels. There are specific courses for teaching early literacy to adults, but most of these teachers claimed not to have studied this.

To answer the first research question, the ways teachers presented letters were analysed in relation to autonomous or ideological views of literacy, by investigating if letters are presented in relation to literacy practices which students participate in, in their daily lives. The second question was answered by analysing how teachers relate letters to phonemes and pronunciation. The third question was answered by examining how teachers present letters through various artefacts. At this point, the way the letters were presented through handwriting was also analysed.

Findings

Teachers’ presentations of letters

In some of the classrooms, illustrated cards with the alphabet were displayed on the wall, usually above the whiteboard. These were occasionally referred to by teachers. However, as noted above, only a limited amount of classroom time was focused on single letters and their pronunciation. The majority of each lesson was dedicated to language learning more generally, in both oral and written form. Thus, for the main part of each lesson, one could say that an ideological perspective was used and that, within their learning environment, teachers and students used literacy holistically. Accordingly, literacy was used in context, for example in relation to a discussion on TV programmes (see excerpt 1 below), and included in the exercising of general language skills, such as asking and answering questions or writing short messages. However, there were occasions when letter training was explicitly addressed and letter learning was treated as something that may, or should, be taught separately, particularly in the initial stages of the language learning process, as was the case with one of the alpha groups.

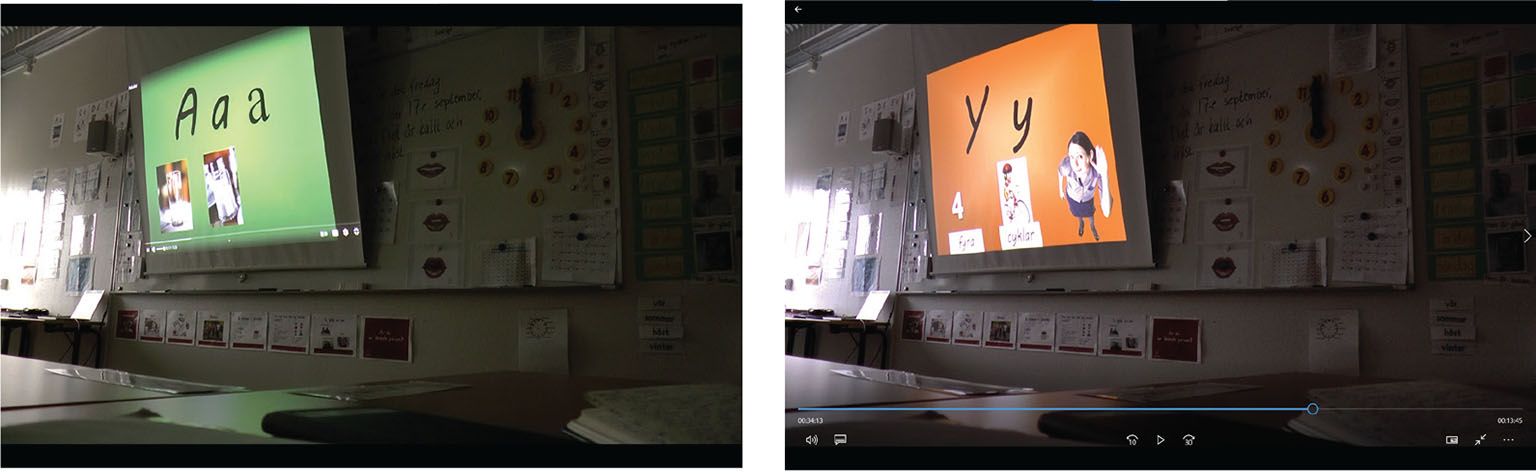

The teaching of specific letters on these identified occasions took two distinctive forms. First, single letters were the focus of some lessons, with the teacher presenting the orthography and pronunciation of individual letters, as well as identifying words that use these letters. This type of teaching occurred only in the two alpha groups. Second, in three of the A courses, students worked with exercises related to single letters. In one course this consisted of locally produced material and in the other two a digital programme whereby students completed individual exercises that helped them practice reading single letters and syllables. We will first present examples of teaching of single letters.

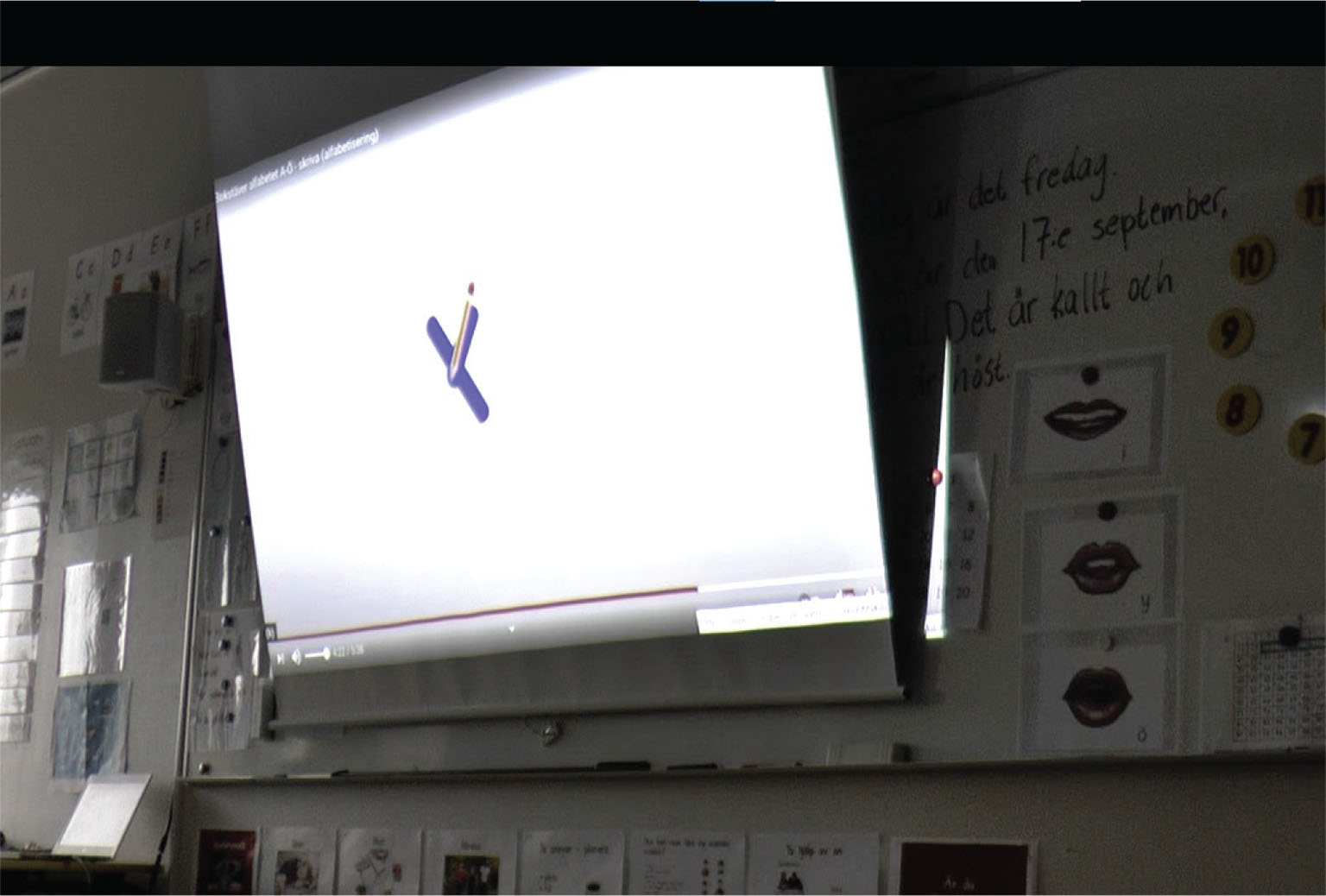

Most of the occasions where single letters were pointed out occurred in one of the alpha groups with one particular teacher. With this group, whole sessions were dedicated to specific letters and on systematically practicing the reading and writing of them one at a time and finding them in words. This content covered the main part of three whole 90 minute sessions, with the group divided into two subgroups so that each subgroup was observed for a total teaching time of 270 minutes. Then, for each letter at a time, the teacher wrote the letter on the whiteboard, said its sound and letter name, asked students to suggest words using the letter, showed them how the letter was to be written, showed them an instructional film and then invited the students to practice writing the letters themselves. The letters presented were the same as in the instructional film – <f t e>, <b y x>, <b y ö>, and <å h d>.

During these lessons, there was some letter instruction that did not follow Swedish standards and some aspects that were not adapted to adult L2 learners. This was particularly the case with the instructional films that were taken from YouTube and that were not official teaching materials. In these films, some letters were not pronounced in standard Swedish, for example the letter <x>, /ɛks/, was pronounced /kes/ and /køs/. Neither the teacher nor the films pointed out phonetical features that are known to be difficult for L2 learners of Swedish, such as lip-rounding when pronouncing the letters <y> and <ö>. The differences between pronunciation of the letters <v> and <f>, as well as <b> and <p> (which phonetically are described as either ‘voiced’ or ‘not voiced’), were explained by the teacher using the terms ‘hard’ (<v> and <b> ) and ‘soft’ (<f> and <p>). In our experience, the expressions ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ are often used in literacy teaching in the early grades in primary school, but, as mentioned earlier, in relation to vowels. This hard/soft distinction is also used in a guide for teachers that is used in SFI (Gren Edvardsson & Gripner, 2019), but then in relation to the phonemes /k/ and /g/, which are called ‘hard’ while the phonemes /ɕ/ and /j/ are called ‘soft.’ Phonetically, the contrast between these sounds is called explosives versus fricatives.

The other type of activity, addressing the issue of the coding and decoding of letters, involved the use of a digital teaching tool. One of these tools was, according to its product website, ‘inspired by the Witting methodology’.2 According to the product description on the webpage, the materials were originally created for children in the early years of primary school. In a film presenting the tool, it says that it works equally well for ‘adults and individuals with a mother tongue other than Swedish,’ even though there have been no discernible adaptations to the content for either adults or other L2 learners. Learners are divided into stages and in the film it is claimed to be important for teachers to make sure that all learners reach at least the first stage, called ‘reading maturity’ (läsmogenhet), although there is no information on how this is applicable to adults. This tool seems to be popular with SFI teachers: several have added comments about the tool on the webpage. The tool is designed so that students can work progressively by reading first single letters, then syllables (CV) and then three letters (CVC). That the tool was created for children may be understood from some instructional pictures, where the learner is depicted as a child.

To sum up, the teachers in this study may be understood as generally following an ideological view on literacy as the main part of their teaching that was holistic, with literacy included in other work in the classroom. However, the existence of alpha groups at two of the four project schools, and the common use of a digital exercise tool, indicate that there exists an assumption that letters should be taught explicitly and separately. Also, the use of these instructional YouTube films and digital software implies that teachers feel they need additional support when teaching letters. The teacher aids used here represent an autonomous language perspective as letters are treated separately and only contextualised to a limited extent. They were not adapted to adult L2 learners, nor were they professionally reviewed. They were not available through established textbook publishers, but through public and mediated channels like YouTube and a private company.

The teachers in our study do not seem to have an established methodology that they follow for early literacy education in SFI. Their teaching seems to depend on their own assumptions and on the tools and materials that they may find. The fact that they are not used to explaining single sounds phonetically, but rather by using expressions such as ‘soft’ and ‘hard,’ indicates that teachers rely on teaching traditions that are common in Sweden in the earlier years in primary school rather than on research-based knowledge for adult L2 learners. Even if most of the SFI teaching observed here can be understood as following an ideological perspective on emergent literacy and letter learning, the teaching strategies demonstrated for letter learning seem to be used rather unconsciously, with traces of both autonomous and ideological views on literacy.

How letters are related to pronunciation

In addition to the occasions when the teachers presented individual letters to their students, as discussed above, we identified 16 occasions where teaching explicitly related letters to pronunciation. We did not observe any occasion where the relationship between letters and pronunciation was a topic that the teacher had planned for a lesson, except for the explicit teaching of single letters above; but, in all cases, we noted that the highlighting of this relationship was initiated as a result of other reading and writing activities. These occasions were drawn from across the range of teachers and courses included in our study; all were related to reading out loud in class. During our observations, the teachers also spoke individually to some students about their writing. These occasions, however, were not sufficiently well documented to allow for an analysis, as video cameras were not directed at the students.

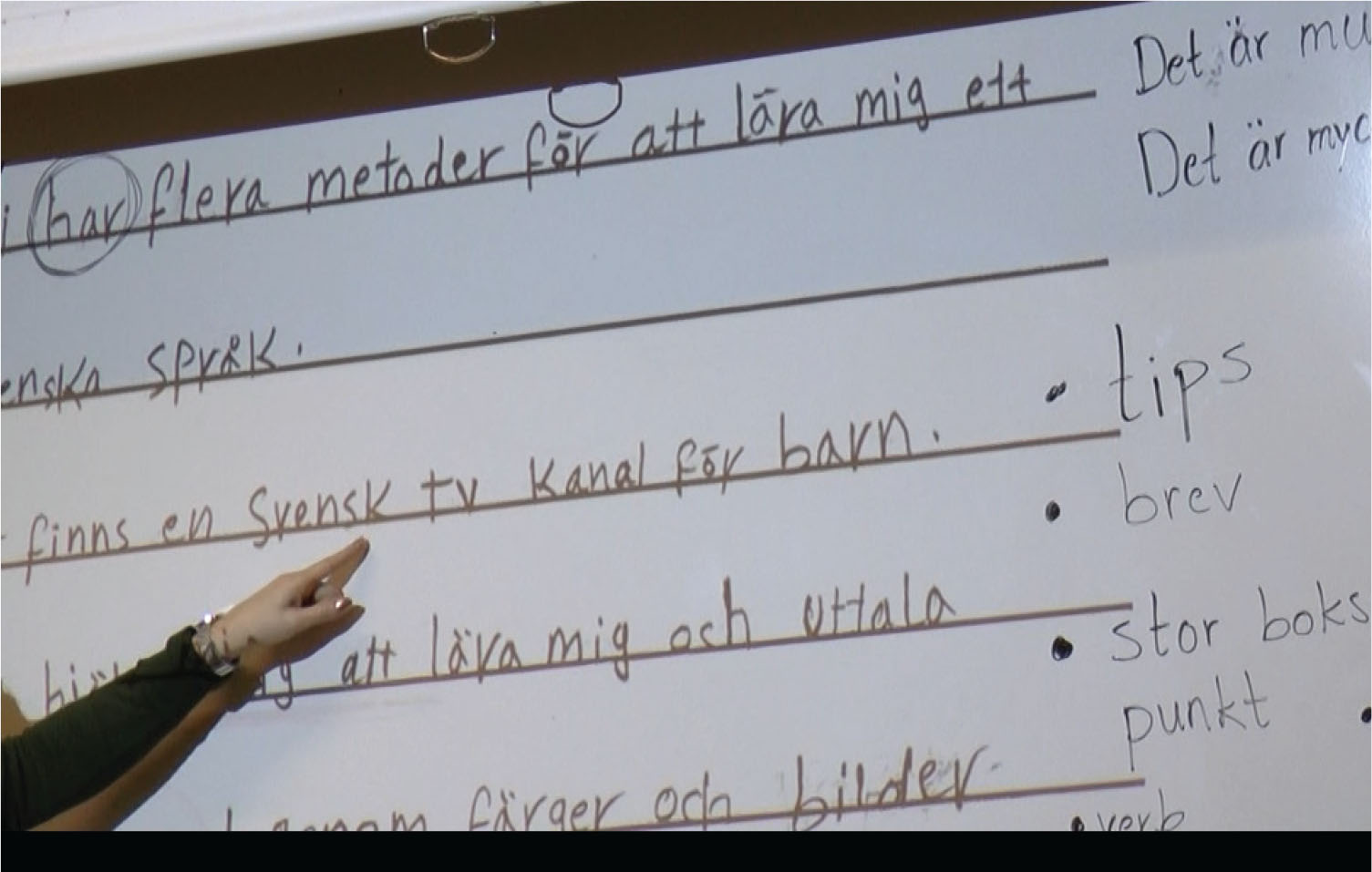

Of the identified 16 occasions, two focused on decoding, one on spelling, and the others on pronunciation in relation to written language. During one of the decoding occasions, the teacher was squatting in front of a student, referred to the letter <ä> and said: ‘Det är en glad vokal men inte e, ä’ (It’s a happy vowel but not e, ä3). During the other occasion, the teacher of this B group projected a female student’s text onto the screen and asked her to read it out loud (Picture 1 and Excerpt 1)

Excerpt 1

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

E: [Läser] e det finns en svenska TV kanal för barn. L: Vad står det hur s slutar det finns en sven [pekar] s k E: svensk TV L: Ja! E: e kanal för barn L: Ja bra E: Bara svensk? Jag tänker r inte L: Jaha du trodde att det var ett r E: Ja L: Ja ja ibland r och v liknar varandra lite grann mm |

S: [Reads] um there is a svenska [Swedish] TV channel for children. T: What does it, how does it end there is a sven [points] s k S: svensk TV T: Yes! S: um channel for children T: Yes good S: Only svensk? I think r not T: Oh you thought it was an r S: Yes S: Yes sometimes r and v look a bit similar Mm |

In this extract, the student misreads the word ‘svensk’ as ‘svenska.’ She then corrects herself in line 5, but in line 9 asks ‘Bara svensk? Jag tänker r inte.’ The teacher interprets this as a misreading of the way the student has written her ‘v.’ The teacher then concludes that this misreading was due to the fact that the letters <r> and <v> may look similar. Here the letter in question is a <k> written like <v>, and it is not clear if this is what the student meant with her question. The teacher did not, however, address the orthographic form of the <k>.

In the teaching occasion dealing with spelling, the teacher in an A group directs students’ attention to the spelling of the sound /j/ in words such as ‘gjorde’ and ‘helgen.’ The /j/ sound has an irregular spelling in Swedish, which commonly gives rise to problems with misspelling, decoding, and pronunciation.

Of the other cases that link a discussion of letters with pronunciation, the teachers focus on pronouncing (1) the /l/ in the word ‘plats,’ (2) the <o> like the /u/ in ‘torsdag,’ (3) the <e> in ‘kafé’ compared to ‘kaffe’ and the <u> in ‘bulle,’ (4) the <r t> in ‘vart,’ (5) the /j/ in ‘hjälpte’ and the /ʃ/ and /sk/, in front of certain vowels, (6) the words ‘tretton’ and ‘femton’ as examples of the pronunciation of the long vowel /e:/, and (7) other common differences between written and oral speech. In the first case, the teacher compares the pronunciation of /plats/ and /pats/ and exemplifies this with the word ‘busshållplats.’ In the second case, the teacher turns students’ attention to words where <o> is pronounced /u/, and /o/, respectively, and asks students for several examples. The third case includes a reference to prosody as accent and stress as represented by the difference between the two Swedish words ‘kafé’ /kafé:/ and ‘kaffe’ /kàfːə/. On this occasion, the teacher says that the pronunciation of <u> in ‘bulle’ is similar to <u> in ‘Umeå,’ although there are differences between the pronunciation of the letter <u> regarding both vowel quality and quantity (/bөlːə/ and /ʉ:mɛɔ/, respectively). The fourth case deals with the <r t> that is pronounced /ʈ/ in ‘vart,’ a sound that most L2 learners of Swedish have problems with. In the fifth case, the teacher explains the rules for pronouncing <j> and <sk> in front of certain vowels, which is also a common difficulty for both L1 and L2 learners of Swedish. In the sixth case, taken from one of the YouTube films shown to the students, the pronunciation of <e> as a long [e:] is exemplified with the words ‘tretton’ /trɛton/ and ‘femton’ /fɛmton/, where <e> is pronounced with a short [ɛ]. The last cases are several, where teachers compare the spelling and pronunciation of, for example, ‘farlig’ and /fa: ɭig/, ‘morgon’ and /mɔr:ɔn/, ‘de’ and /dɔm:/, and ‘sig’ and /sɛj:/.

In these examples, teachers directed students’ attention to decoding and coding letters, and they related pronunciation and the written language to each other. This occurred in the context of reading and writing activities where the teachers pointed out features that they perceived students were having problems with. From these examples, the inconsistency that we noticed previously among teachers and with the teaching tools used to support the explanation of the relationship between pronunciation and spelling is verified. The SFI teachers in this study consistently referred to the rules for spelling and to the pronunciation of the phoneme /j/ versus /g/ and /ʃ/ versus /sk/ in relation to vowels in ways that reflect the methodologies and approaches that, in our own experience from teaching and teacher education, are used in literacy education in Swedish primary school. Furthermore, teachers appeared inconsistent when relating letters and pronunciation to each other. Features such as the pronunciation of <e> and <u> depending on prosodic features at a phrase or sentence level – an important feature for L2 learners of Swedish – were not pointed out to students.

Orthographic presentation of letters

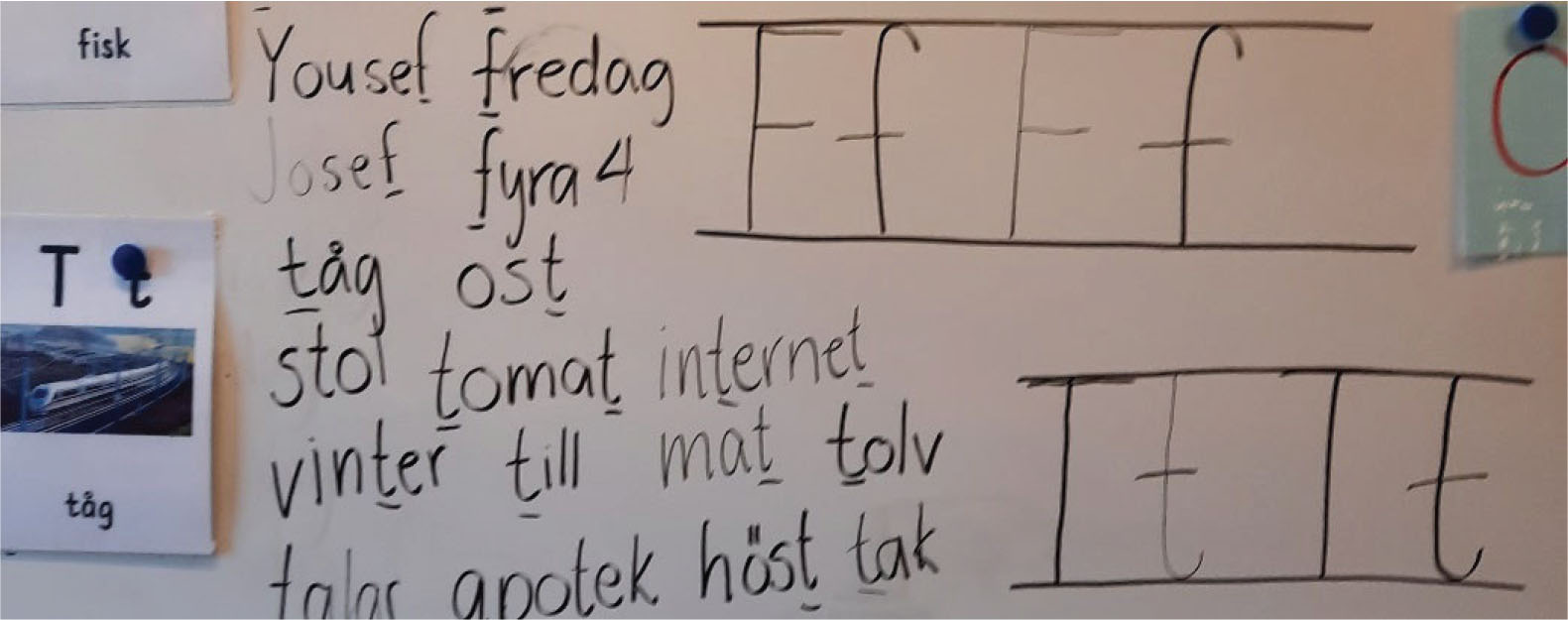

The third research question addressed by this study about the orthographical representation of letters is answered by analysing how letters are orthographically represented through various artefacts. We have also analysed the form of the letter being presented. The examples we have chosen to illustrate here are taken from the lessons of the teacher for one of the alpha groups. In the presentations of the letters mentioned earlier, this teacher writes the letters on the whiteboard between two lines that she calls a ‘floor’ and a ‘roof’ respectively. She explicitly tells students to write ‘on the floor.’ In the words to the left that exemplify her point, she has underlined the letter in question (Picture 3).

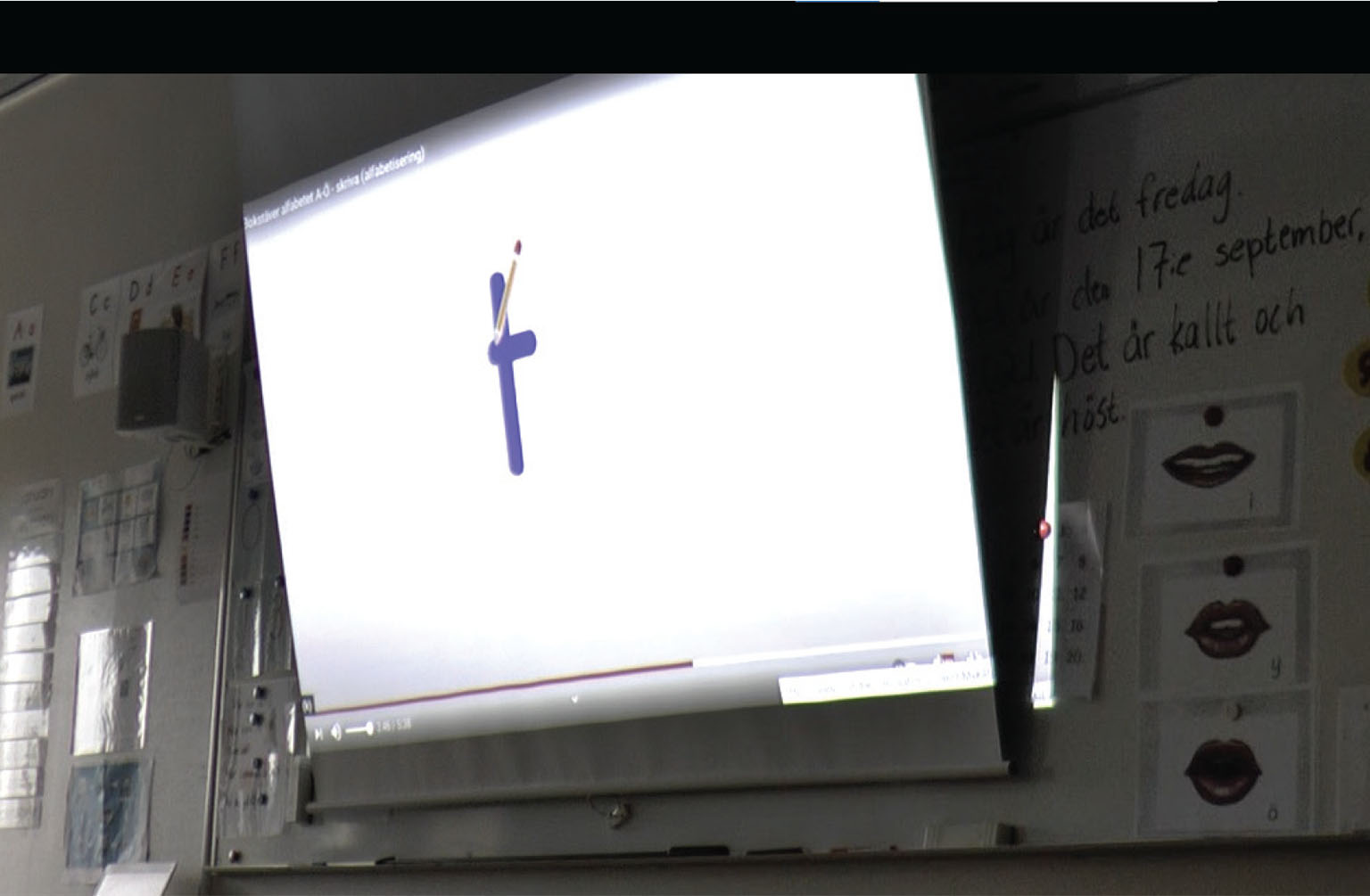

In Picture 3, the <t> is written as high as <T>; however, according to standard Swedish orthography, it should be lower. Note that in the picture of the train to the left, used to illustrate <T> and <t>, this part of <t> is hidden behind the magnetic holder. That letters are written in non-standard forms also occurs in the YouTube films, where letters are formed stroke by stroke (Picture 4).

In the film depicted here, the <t> is written without a curve at the end. The teacher did not address how letters are written stroke by stroke, even though this is deliberately demonstrated in the YouTube film. The teacher’s own demonstration in several cases did not follow the pattern that is traditionally recommended for preparing students for fluent handwriting. Also in the film above, <t> is written with the cross line from right to left, where left to right would be the direction in cursive writing. This is also the case in Picture 5, where the writing of <x> is demonstrated from right to left.

The teacher uses the metaphors ‘floor’ and ‘roof’ when explaining the writing of <y> when she says:

Excerpt 2

| L: Hittills har vi skrivit på golvet [pekar på golvet i klassrummet] men y [visar hur hon gräver med en spade i golvet] y ner där. | T: Until now, we have written on the floor [points to the floor in the classroom], but y [mimes how she digs with a shovel into the floor] y down there. |

In this case, she does not make sure that students understand the connection she makes between the bottom line in writing and the classroom floor and between drawing the tail of the <y> below the line and her digging motion.

On several occasions, particularly in the films, some letters were presented in non-standard orthographic forms (for the history of Swedish orthography, see Greggas Bäckström, 2011; Teleman, 2019), such as the capital <A> and <Y> as illustrated in Picture 6.

When letters are deliberately presented in non-standard forms, this can complicate the literacy process, especially for those students only becoming aware of these possible variants for the first time. The <A> as presented on the left in Picture 5 may not be problematic, but the <Y> written simply as a larger lower case <y> may be confusing, particularly when the <Y> is written a little below the line. The same may be said about another film where <Ä> was presented with the two dots hanging on the left side of the <A> and one where the forms of lower case <u> and the upper case <U> were exchanged. Because standard norms and differences between capital and lower-case letters in Swedish writing are significant, such inconsistencies can complicate students’ learning.

Discussion

The focus in this article on teachers’ presentation of letter learning as one component of education in basic literacy skills has made it clear that there are inconsistencies in the way literacy is taught within SFI. This article has illustrated the presentation of letters, the teaching of letters related to pronunciation, and their orthographic presentation.

In similarity with previous research, for example Colliander (2018) and Fejes (2014), this study highlights the importance of teachers who are educated to teach adults. The problem with general lack of knowledge among teachers in SFI about phonology, which Zetterholm (2017) highlighted, also appears here. With the focus on presentation of letters, this study adds to earlier studies on the teaching of Swedish as a second language, which highlight that teachers need to have knowledge about pronunciation (Grigonyte & Hammarberg, 2018) and particularly prosody (Thorén, 2008).

This study suggests that SFI teachers seem to follow patterns that build on their own and others’ assumptions and traditions that have their roots in the teaching of children and that are shaped by the material they have at hand. They seem to rely to a lesser extent on conscious decisions based on research-based knowledge. That traditional educational practices that have been developed for children’s L1 learning are inadequate for this group of adult L2 learners has been established in earlier research (see e.g. Filimban et al., 2022; García, 2009; Kurvers, 2015; Peyton & Young-Scholten, 2020). On the occasions identified in this study, there were no signs of teaching being adapted to individual students’ earlier knowledge and experiences, such as earlier literacy skills. These teachers appeared to be unaware of the importance of the orthographic presentation of letters. However, they seemed to draw both on holistic views of literacy learning, which are compatible with an ideological view on literacy (Street, 1995, 2009), and on Swedish teaching traditions in the teaching of L1 children, which are more compatible with an autonomous view on literacy in the sense that they sometimes focus on single letters and their pronunciation and orthographic form. Traditions associated with the teaching of Swedish L1 children do not equip teachers when it comes to knowledge of Swedish phonology or orthographic standards. Thus, while the teachers in this study to some extent relied on the autonomous focus on letters and phonics, this became problematic when their prosodic knowledge in relation to letters and spelling was insufficient. We argue that when teachers are not aware of the phonetic and phonological challenges facing L2 learners, such as prosody (Thorén, 2008), they may not give students enough support in their development of early literacy skills, particularly on a letter level, as was the case here. For teachers to be able to teach single letters in Swedish, they need to be aware of the variance in the pronunciation of vowels such as <e> and <u> depending on prosodic features at a phrase and sentence level. It may seem that this is a minor concern, given that explicit letter teaching represents only a small part of the overall teaching and that an ideological holistic approach to language learning predominated, because this could be a better way for SFI students. However, if teachers miss out on phonetic and phonological knowledge, which is important for the development of literacy, they may not be able to identify difficulties for students and may even create unnecessary stumbling blocks for them.

Similarly, the inconsistent orthographic presentation of letters creates additional difficulties for students’ development of basic literacy skills. Inconsistency in letter writing is particularly problematic in the early stages of emergent literacy, when students are still learning to recognise and form the letters, and when they are learning to connect graphemes to phonemes. The use of the YouTube films in these examples shows that teachers feel the need for support and that there is a shortage of high-quality literacy tools that have been developed according to research.

We conclude that there is a strong need for the development of basic literacy education in SFI that includes both teacher knowledge and teaching aids. Additional research is needed to develop teaching methods that are research-based and that are effective in the teaching of L2 adults. When it comes to Swedish phonology and orthography, such knowledge is available; however, it is not yet included in the requirements for teachers of SFI. While our first research question, which addressed the issue of pedagogical knowledge, indicates that there is a significant need for more research, the second issue – teaching letters in relation to pronunciation – can be seen as a political call for greater teacher competence. This is in accordance with the government’s official investigation on SFI (SOU 2020:66), which included strengthened demands for improved education for SFI teachers. When criticism is raised against the perceived slow pace of student progress in study path 1, students with little or no previous schooling, we argue that these voices should ask instead for changes in the education of their teachers.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Swedish Institute for Educational Research that generously supported the research project of which this study is a part. We also want to express our gratitude to the two reviewers whose comments helped us to improve the article.

References

- Bannert, R. (2004). På väg mot svenskt uttal [On the way to Swedish pronunciation] (3rd ed.). Studentlitteratur.

- Barton, D. (2007). Literacy: An introduction to the ecology of written language (2nd ed.). Blackwell.

- Bialystok, E. (2001). Bilingualism in development: Language, literacy, and cognition. Cambridge University Press.

- Choi, J., & Ziegler, G. (2015). Literacy education for low-educated second language learning adults in multilingual contexts: The case of Luxembourg. Multilingual Education, 5(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13616-015-0024-7

- Colliander, H. (2018). Being and becoming a teacher in initial literacy and second language education for adults [Doctoral dissertation, Linköping University]. DiVA. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-147356

- Copland, F., & Creese, A. (2015). Linguistic ethnography: Collecting, analysing and presenting data. Sage.

- Fejes, A. (2019). Redo för komvux? Hur förbereder ämneslärarprogrammen och yrkeslärarprogrammen studenter för arbete i kommunal vuxenutbilding? [Ready for komvux? How do subject teacher programs and vocational teacher programs prepare students for work in municipal adult education?]. Linköping University.

- Filimban, E., Malard Monteiro, P., Mocciaro, E., Young-Scholten, M., & Middlemas, A. (2022). Pleasure reading for immigrant adults on a volunteer-run programme. In A. Norlund Shaswar, & J. Rosén (Eds.), Literacies in the age of mobility: Literacy practices of adult and adolescent migrants (pp. 131–161). Palgrave Macmillan.

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Blackwell.

- Goody, J. (Ed.). (1982). Literacy in traditional societies. Cambridge University Press.

- Greggas Bäckström, A. (2011). “Ja bare skrivar som e låter”: En studie av en grupp Närpesungdomars skriftspraktier på dialekt med fokus på sms [‘I just write as it sounds’: A study of literacy practices in dialect of a group youth from Närpes, with focus on texting] [Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University]. DiVA. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-49976

- Gren Edvardsson, P., & Gripner, Y. (2019). Lästid: Lärarhandledning [Reading time: Teachers’ guide]. Natur och Kultur Digital.

- Grigonyte, G., & Hammarberg, B. (2014). Pronunciation and spelling: The case of misspellings in Swedish L2 written essays. In A. Utka, G. Grigonyte, J. Kapočiūtė-Dzikienė, & J. Vaičenonienė (Eds.), Human language technologies: The Baltic perspective (pp. 95–98). IOS Press. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-442-8-95

- Hennius, S., Rosén, J. & Wedin, Å. (2016). Grundläggande litteracitet: Att undervisa vuxna med svenska som andraspråk. En kunskapsöversikt. [Basic literacy: Teaching adults through Swedish as a second language. A knowledge overview] Swedish National Agency for Education. https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=3723

- Haznedar, B., Peyton, J. K., & Young-Scholten, M. (2018). Teaching adult migrants: A focus on the languages they speak. Critical Multilingualism Studies, 6(1), 155–183.

- Hornberger N. H., & Skilton-Sylvester, E. (2000). Revisting the continua of biliteracy: International and critical perspectives. Language and Education, 14(2), 96–122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09500780008666781

- Isling, Å. (1991). Från Luther till LTG [From Luther to LTG]. In G. Malmgren, & J. Thavenius (Eds.), Svenskämnet i förvandling: Historiska perspektiv – aktuella utmaningar [The transformation of the subject of Swedish: Historical perspectives – current challenges]. Studentlitteratur.

- Johansson, E. (1988). Bokstävernas intåg: Artiklar i folkundervisningens historia. I [The entrance of letters: Articles in the history of public education] Umeå University, Forskningsarkivet.

- Johansson, E. (1989). Läser och förstår: Artiklar i folkundervisningens historia. III [Reading and understanding: Articles in the history of public education]. Umeå University, Forskningsarkivet.

- Kerfoot, C. (2009). Changing conceptions of literacies, language and development: implications for the provision of adult basic education in South Africa [Doctoral dissertation, Stockholm University]. DiVA. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-26581

- Kurvers, J. (2015). Emerging literacy in adult second-language learners. Writing Systems Research, 7(1), 58–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/17586801.2014.943149

- Leimar, U. (1976). Arbeta med LTG: En handledning [Working with LTG: A guide]. Liber läromedel.

- Lewis, C., & Bigelow, M. (2019). Mobilizing and languaging emotion for critical media literacy. In R. Beach, & D. Bloome (Eds.), Languaging relations across social worlds in educational contexts (pp. 216–234). Routledge.

- Liberg, C. (1990). Learning to read and write [Doctoral dissertation]. Uppsala university.

- Lindmark, D. (2004). Reading, writing and schooling. Swedish practices of education and literacy, 1650–1880. Umeå University.

- Lundgren, B., Rosén, J., & Jahnke, A. (2017). 15 års forskning om SFI – en överblick: Förstudie inför ett Ifous FOUprogram [Fifteen years of research on SFI – an overview: A pilot study within an Ifou FOU programme]. Ifous – Academedia.

- Malessa, E. (2018). Learning to read for the first time as adult immigrants in Finland: Reviewing pertinent research of low-literate or non-literate learners’ literacy acquisition and computer-assisted literacy training. Apples: Journal of Applied Language Studies, 12(1), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.17011/apples/urn.201804051932

- Norlund Shaswar, A. (2014). Skriftbruk i vardagsliv och i sfi-utbildning. En studie av fem kurdiska sfi-studerandes skriftbrukshistoria och skriftpraktiker [Literacy in everyday life and in the Swedish for Immigrants Programme : The literacy history and literacy practices of five Kurdish L2 learners of Swedish] [Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University]. DiVA. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-95745

- Peyton, J. K., & Young-Scholten, M. (Eds.). (2020). Teaching adult immigrants with limited formal education. Theory, research and practice. Multilingual Matters.

- Prinsloo M., & Breier, M. (Eds.). (1996). The social uses of literacy. Sached Books.

- Rashid, T. (2020). Adult literacy/recurrent education programmes in Timor-Leste. Studies in the Education of Adults, 52(2), 134–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2020.1744873

- Rosenqvist, H. (2007). Uttalsboken: Svenskt uttal i praktik och teori [The pronunciation book: Swedish pronunciation in practice and theory]. Natur & Kultur.

- SFS 2010:800. Swedish Education Act, changed SFS 2021:452. https://www.lagboken.se/Lagboken/start/skoljuridik/skollag-2010800/d_4329642-sfs-2021_452-lag-om-andring-i-skollagen-2010_800

- Singh, A. & Sherchan, D. (2019). Declared ‘literate’: Subjectivation through decontextualised literacy practices. Studies in the Education of Adults, 51(2), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2019.1603573

- SKOLFS 2017:91. Kursplan för kommunal vuxenutbildning i svenska för invandrare [Curriculum for municipal adult education in Swedish for immigrants]. https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/vuxenutbildningen/komvux-svenska-for-invandrare-sfi/laroplan-for-vuxoch-kursplan-for-svenska-for-invandrare-sfi/kursplan-for-svenska-for-invandrare-sfi

- SOU 2013:76. Svenska för invandrare: Valfrihet, flexibilitet och individanpassning [Swedish for immigrants: Freedom of choice, flexibility and individual adaptation]. State Public Investigations from the Ministry of Education. https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2013/10/sou-201376/

- SOU 2020:66. Samverkande krafter: För stärkt kvalitet och likvärdighet inom komvux för elever med svenska som andraspråk [Collaborative forces: Strengthening quality and equality in municipal adult education for students studying Swedish as a second language]. State Public Investigations from the Ministry of Education. https://www.regeringen.se/remisser/2020/12/remiss-av-sou-202066-samverkande-krafter--for-starkt-kvalitet-och-likvardighet-inom-komvux-for-elever-med-svenska-som-andrasprak/

- Street, B. V. (1984). Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Street, B. V. (1995). Social literacies: Critical approaches to literacy in development, ethnography and education. Longman Publishing.

- Street, B. V. (2009). The future of ‘social literacies’. In M. Baynham, & M. Prinsloo (Eds.), The future of literacy studies (pp. 21–37). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Teleman, U. (2019). Svensk ortografihistoria: Från 1200-tal till 1700-tal [The history of Swedish orthography: From the 13th to the 18th century]. Lund University.

- Thorén, B. (2008). The priority of temporal aspects in L2-Swedish prosody: Studies in perception and production [Doctoral dissertation]. Stockholm University.

- Wedin, Å. (2007). Literacy and power: The cases of Tanzania and Rwanda. International Journal for Educational Development. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2007.09.006

- Wedin, Å. (2010). Vägar till vuxnas skriftspråksinlärande [Ways to adults’ learning of literacy]. Studentlitteratur.

- Wedin, Å., Rosén, J., & Hennius, S. (2018). Transspråkande och multimodalitet i grundläggande skriftsspråksundervisning inom sfi [Translanguaging and multimodality in beginner written language education in sfi]. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 23(1–2), 15–38. https://open.lnu.se/index.php/PFS/article/view/1468

- Wedin, Å. & Norlund Shaswar, A. (2019). Whole class interaction in the adult L2-classroom: The case of Swedish for Immigrants in Sweden. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies. 13(2), 45–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.17011/apples/urn.201903251959

- Wedin, Å. & Norlund Shaswar, A. (2021). Litteracitetspraktiker (-praxis) i vardags- och samhällsliv: Skriftspråksvanor hos svenska sfi-elever på studieväg ett [Literacy practices in everyday and societal life: Literacy use among Swedish SFI students in study path one]. Nordic Journal of Literacy Research, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.23865/njlr.v7.2797

- Witting, M. (1974). Att lära läsa: Utan bild och läsebok: En övningsserie med metodiska anvisningar [Learning to read: Without pictures or readers: training exercises and practical instructions]. Hermod.

- Young-Scholten, M. (2015).Who are adolescents and adults who develop literacy for the first time in an L2, and why are they of research interest? Writing Systems Research, 7(1), 1–3. http://dx.doi.org10.1080/17586801.2015.998443

- Zeichner, K. (2001). Educational action research. I P. Reason, & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (pp. 273–283). Sage.

- Zetterholm, E. (2017). Swedish for immigrants: Teachers’ opinions on the teaching of pronunciation. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Monolingual and Bilingual Speech 2017. Institute of monolingual and bilingual speech, Chania, Greece.

Fotnoter

- 1 2020–2022, financed by the Swedish Institute for Educational Research, no 2019/0001.

- 2 https://www.dyslexi.eu/tradet-web-2/ Translation by the authors.

- 3 In Swedish, the difference between the pronunciation of <e> and <ä> is that the latter is a more open vowel, pronounced with a slightly more open mouth. Both vowels are unrounded.