Figure 1. Interactional positions in terms of speech activity and literacy competence High degree of speech activity.

Peer-reviewed article

Eva Hultin*,

Dalarna University, Sweden

Abstract

The aim of this study is twofold: firstly, it aims to explore the interactional conditions in terms of democratic qualities constituted in collective writing in a primary school classroom; and secondly, it aims to examine whether a set of deliberative criteria is fruitful as an analytical tool when studying classroom interaction. Theoretically, I turn to New Literacy Studies for understanding the writing classroom as a literacy practice and the actual (collective) writing as literacy events. The study has an ethnographic approach in which classroom observations were conducted during a collective writing process involving six nine-year-old children and their teacher. The observations included, two lessons, divided into 3 hours, which were observed, videotaped, and transcribed. The teacher had planned for a strict interactional or didactical order during the collective writing in which the children were to respond individually. However, the children responded in a different manner by starting a vivid dialogue in which they negotiated both the form and the content of the story. The analysis shows some deliberative qualities in this classroom interaction, while some other qualities were not evident. Furthermore, the analysis showed that the set of deliberative criteria was useful in visualizing both existing deliberative qualities in the interaction and the potential for developing such qualities.

Keywords: Collective writing; classroom interaction; deliberative communication; ethnography

Received: May 2016; Accepted: January 2017; Published: March 2017

*Correspondence to: Eva Hultin, Dalarna University, 791 88 Falun, Sweden. Email: ehu@du.se

©2017 Eva Hultin. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Eva Hultin. “Children’s Democratic Experiences in a Collective Writing Process – Analysing Classroom Interaction in Terms of Deliberation.” Nordic Journal of Literacy Research, Vol. 3, 2017, pp. 26–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/njlr.v3.472

The national curriculum for comprehensive school (Lgr11) in Sweden, as well as the Swedish School Law (2010:800), stresses that school should not only develop children’s knowledge and skills in different subjects, but also provide a democratic citizenship education. In Lgr11 it is particularly emphasized that:

It is not enough to transmit knowledge about the core values of democracy in teaching. Teaching should be organized in democratic forms and prepare the pupils for participating actively in community life.

(Skolverket, 2001, p.4; the author’s translation)

As can be seen in the quote above, the emphasis on democratically organised teaching is not related to a specific subject, but to all teaching in school. The fact that schools are given the specific responsibility of educating citizens motivates the study of whether schools have the preconditions necessary to realise society’s democratic ambitions for comprehensive education. Are the democratic ambitions in educational policy texts merely high ideals or can they be realised in the everyday practices and activities in schools? These questions are approached in this article by focusing on the opportunities children have for gaining democratic experiences as they participate in classroom interaction in everyday literacy activities.

More precisely, this study comprises an analysis of classroom interaction when six children in the third grade of primary school collectively write a story with their teacher. As this study is placed theoretically in the field of New Literacy Studies, I understand the writing classroom as a literacy practice and the actual (collective) writing as literacy events (Barton, 1994). The teacher had planned for a strict interactional or didactical order during these literacy events by introducing a specific methodology, called the Makete Method. This method consists of ten questions, the answers to which form a story (described in greater detail in the method section below). The children were expected to answer one question each. However, the children responded in a different manner by starting a vivid dialogue, disregarding “whose” question was addressed, and thereby negotiating both the form and the content of the story. The children’s vivid participation during the lesson evoked my interest in exploring whether these interactional processes could be understood as containing democratic qualities. At the same time, I saw a suitable opportunity to also explore the pragmatic values of a set of criteria for deliberative democratic interaction both as analytical tools for classroom interaction as well as normative guidelines for the way teachers organize classroom interaction (Englund, 2000). In the Nordic context, educational researchers have suggested deliberative communication as a way of realising democracy-fostering assignment given to schools (Englund, 2000, 2006; Roth, 2001). Englund’s didactical proposal on deliberative communication is the most widespread in Sweden (Englund, 2000; Hultin, 2007a) and it was also normatively sanctioned by the Swedish National Agency of Education when it published his proposal, Deliberative communication as a value foundation – historical perspectives and current preconditions (2000). Therefore, the deliberative criteria used in this article are Englund’s, which are presented in Table 11:

This didactical proposal on deliberative communication by Englund has not been anchored in empirical studies of classroom interaction, but is grounded in educational philosophy and social theories. Since then, a handful of empirical studies on deliberative communication in schools in the Nordic context have been carried out (Forsberg, 2011; Thyberg, 2012; Andersson, 2012; Tammi, 2013; these studies are described in greater detail below). None of these studies, however, were conducted in primary schools among younger children; the educational setting in focus in this study. As deliberative communication is suggested as a way of organising schools’ value-based education (Englund, 2000, 2006), I would argue that it is necessary to conduct empirical research on the conditions for realising deliberative communication in classroom interaction in order to evaluate the deliberative proposal’s didactic value, which the present study aims to contribute with.

Therefore, the aim of this study is twofold; firstly, it aims to explore interactional conditions in terms of the deliberative qualities constituted in collective writing in a literacy practice in primary school; secondly, it aims to explore the pragmatic value of Englund’s deliberative criteria for educational research and practice. The following research questions have been formulated in relation to the twofold aim stated above:

Although there are few empirical studies of classroom interaction as deliberation, the research on classroom interaction is vast and has been carried out in many different research traditions (Lindblad & Sahlström, 2000). Earlier research on classroom interaction has repeatedly shown and argued that traditional teacher-led classroom interaction follows a specific pattern, the so-called IRF (initiative-response-follow-up) (Sinclair and Coulthard, 1975) or IRE (initiative-response-evaluation) (Mehan, 1979; Cazden 1988) where the teacher is in control of the interaction and its agenda, through asking questions in order to control and evaluate the children’s knowledge – an interactional pattern which has been labelled as authoritarian. Thus, the deliberative proposal can thereby be understood as an alternative to this monologic classroom discourse.

The relationship between democracy and education has also been thoroughly studied and reflected on by educational researchers and (educational) philosophers (i.e. Kant, 1784/1992; Dewey, 1916). Earlier studies have shown that even though there has been a societal consensus that school should have this democratic role, there have been several interpretations of its meaning and didactical design (Boman, 2002; Larsson, 2007; Biesta, 2007). The contemporary educational philosopher Biesta says that historically it is possible to discern two main ways of understanding the relationship between democracy and education: education for democracy and education through democracy (2007). Education for democracy comprises the transmission of values, knowledge, and skills to students so that in the future they will be able to act as democratic citizens. Education through democracy is about students acquiring democratic values, knowledge, and skills through engaging in democratic processes in school.2 The understanding of education through democracy can be derived from Dewey’s classical work, Democracy and Education from 1916, in which he stresses that in a vital democracy, democracy is not only a form of government but also a form of life. In this work, Dewey also stresses that a form of life, a community, is always held together through the sharing of common interests, which are constituted in communication. Furthermore, he emphasizes that the degree of democracy and learning abilities in a community has to do with the participants’ opportunities to share differences and ideas with each other and with other communities (1916).

Englund’s concept of deliberative communication takes its philosophical departure from this Deweyan idea of democracy as a form of life (Englund, 2006); the understanding of education through democracy is also the theoretical starting point for this study and its aim, to explore the interactional conditions in terms of democratic qualities constituted in collective writing in a primary school classroom, can be understood as another way of asking whether democracy as a form of life exists in the studied interaction. A recurrent line of thought in the above-mentioned work by Dewey is that social life, embedded in communication, is constituted in historic continuity (1916). If the continuation of the communicative, social life of classrooms is called IRE/IRF, as earlier research on classroom interaction claims, then the democratic aspiration might be difficult to attain.

Beyond Dewey, deliberation as a concept has its theoretical residence in Habermas’ theories on communication and democracy (Habermas, 1987). Deliberative democracy has been put forward as a complement to representative democracy. If a democratic body, such as a parliament, is to reach sustainable political decisions, the representatives cannot merely cast their vote on a proposal. On the contrary, it is essential, according to the deliberative tradition, to reach a decision on a solid argumentative base. The prerequisites for this are that all concerned parties should be engaged in a deliberation on the matter. In that way the question is illuminated and argumentatively penetrated from different perspectives. All parties should also meet as equals and put aside their differences (as socio-cultural or economical) and strive to reach the best argument for all concerned (Eriksen & Weigård, 2000). In order to realise deliberative democracy, it is necessary for citizens to be equipped with both deliberative attitudes and skills. It is in relation to this context that several educational researchers have argued that the school’s and the educational system’s democratic mission should be realised in terms of deliberation (Gutmann & Thompsson, 1996; Englund, 2000; Roth, 2000).

Both deliberative democracy and deliberative communication in school have been criticised for depicting unrealistic ideals that no real practice, situation or people could live up to (Lewin, 2003; Dahlstedt, 2000; Hermansson, Karlsson, & Montgomery, 2008; Hultin, 2007a; Hultin, 2007b, 2003; Almgren, 2006; Papastephanou, 2010). These researchers emphasize, among other things, that we live in a power-embedded world, in and out of school, which is constituted of and constitutes power relations (which can be categorised in many different ways, such as gender, race, age, and socioeconomic status). The consensus reached, in such a world, is tainted and/or limited by the power relations at play. I share these objections to the concept of deliberation (Hultin, 2007a); but still I think it is possible, and even fruitful, to explore whether classroom interaction can be understood as comprising deliberative qualities, not least because Englund makes the crucial distinction between deliberative qualities in communication and deliberative communication (as fully realised) when he introduces his criteria (2000), which makes the proposal far more realistic than it would have been without that distinction.

As mentioned above, only a few empirical studies of deliberative communication have been conducted in the Nordic context (Forsberg, 2011; Thyberg, 2012; Andersson, 2012; Tammi, 2013). These four studies evaluate a teaching situation designed or arranged to be deliberative. Tammi’s study is particularly relevant to the current study, as it focuses on children in a similar age group to those in my study (9–10 years old) and has a similar methodological approach, as the material consists of video and observational data from “nine deliberative exercises” (Tammi, 2013, p. 77). The result of the analysis shows three dilemmas in the deliberative teaching: the dilemma of the width, the dilemma of the depth, and the dilemma of feasibility. The first dilemma (width) points at the fact that pupils participate differently, some are more active than others and some are more power-sensitive and might avoid disagreeing with the teacher. The teacher feared that the deliberations might widen the developmental gap between students; the challenge in relation to this dilemma is widening deliberations and “giving more responsibility for argumentation to pupils”. The second dilemma (depth) deals with what kind of questions the pupils should be allowed to deliberate; the challenge in relation to this dilemma is to open up the floor for pupils’ initiatives regarding what to deliberate. The third dilemma (feasibility) comprises the tension between the ambition of creating a democratic school practice, on the one hand, and the teacher’s need for control over the classroom activities so all pupils have a possibility to learn, on the other; the challenge in relation to this dilemma is to take “the responsibility for drawing a temporary conclusion (implying that issues remain discussable)” (Tammi, 2013, p. 83). This study shows in a very convincing way both the potentials and challenges that follow attempts to organise deliberative situations in school. Another study of specific interest for the present study is Liljestrand’s study (2002) which does not focus on deliberative communication in classroom per se but on classroom interaction in order to analyse its potentialities for preparing students for political citizenship. One particularly interesting result is that the students are mostly constructed as citizens-to-be in the discussions, as the students do not participate as knowledgeable citizens but as students answering and commenting on questions that the teacher has initiated.

This study is part of a larger ethnographic research project on the digitalization of early literacy practices in school and digitalization’s implications for children’s literacy learning and teachers’ professional development (Hultin & Westman, 2013a, 2013b, 2014). Thus, I have conducted fieldwork for two and a half years in the literacy practice of this study and I knew the children and the teacher quite well when the literacy activities described in this study took place. This ethnographic fieldwork consisted of week-long classroom observations every term, interviews with the teacher and most of the children, and collecting and analysing all texts produced by six children in the first grade (Hultin & Westman, 2013b; Hultin & Westman, 2014). During the weeks in the field, I participated in and studied most of the activities the children had during their school days: different subjects such as mathematics and natural science, as well as non-curricular activities such as eating lunch, playing in the schoolyard during breaks, and waiting in the hall for the teacher before lessons. The fieldwork carried out is of importance for the present study in three main ways. First, the understanding and knowledge of the literacy practice and its agents (teacher and children) creates prerequisites for a deeper understanding of the literacy activities analysed in the present study. This is also in line with the theoretical understanding of literacy activities (events) as always taking place within literacy practices in the field of New Literacy Studies (Street, 1995; Barton et al., 2000; Heath, 1983), which is the theoretical underpinning of both the bigger project and this part of it.

Secondly, spending time in the field is also important for ethical reasons. Even though the children, their parents and the teacher all gave their informed consent for participation in the study, I noticed how it became easier and easier for children to ask questions about the research and also to decline to participate as we got to know each other better. In other words, visiting the classroom over a longer period of time allowed for more solid informed consent from the children. Thirdly, as I had repeatedly visited the classroom, the teacher and children had got used to my presence. Of course, it is difficult to evaluate how much the teacher and the children were influenced by my presence and the presence of the video camera, but over time I noticed that the interactional roles of the children in the classroom interaction were quite stable; for instance, some children were more active than others, and some children were more listened to than others. The literacy activities analysed in this study were literacy activities that the teacher had done earlier with the children. Furthermore, these literacy activities were not planned because they were suitable material of my study, but rather were part of the recurrent literacy activities in class. The interaction studied can therefore be labelled as the everyday classroom interaction of the literacy practice. An interest in everyday literacy activities (events) in literacy practices in school have been pursued in earlier studies within the field of New Literacy Studies in the Swedish context (Ewald, 2007; Hultin & Westman, 2013a, Jönsson, 2007; Schmidt, 2013; Skoog, 2012; Tanner, 2014). These studies focus various aspects of the learning potential of the literacy practices investigated. However, the potential of democratic learning and experiences in the studied literacy practices have not been explicitly investigated. The earlier mentioned empirical studies of deliberation have not studied everyday activities in school, as it has been pointed out earlier, but designed deliberative situations in classrooms (Forsberg, 2011; Thyberg, 2012; Andersson, 2012; Tammi, 2013), while this study can shed light on the question of whether everyday interaction in school can be understood as comprising deliberative qualities.

As mentioned above, the empirical material for this study consists of three hours of classroom observation during which the children and the teacher collectively wrote a story. The three hours took place over two occasions; on the first occasion (90 minutes) the children and the teacher wrote the story collectively, and one week later, they revised the same story together (90 minutes). Table 2 shows the ten questions of the Makete Method, which was used during the first occasion.3

The teacher introduced this method in class in order to support a clearer narrative structure in the story, as the answers to the questions build a narrative with character(s), plot, time, setting, etc. The children’s collective story as a text is actually not part of the analysed material, but since it is referred to in the quoted transcripts of the analysis, I display the final version of it in Table 3:

The interaction during these three hours of collective writing and revision was documented on video with one fixed camera that caught all the verbal interaction of the six children and the teacher as well as the white board where their (emerging) story was seen. Earlier research has pointed out that fixed cameras, especially if only one is used, cannot catch all the nuances of classroom interaction, especially the unofficial interaction between children (Sahlström, 1999; Blikstad-Balas & Sørvik, 2015). As the purpose of this article is to analyse the official classroom interaction while the children and teacher write and revise a collective story, I claim that one camera is sufficient, even though not every child’s body language is captured equally well, since those interactional dimensions are not focus of the analysis. An advantage of one fixed camera over a handheld flexible one is that it draws less attention. The children were interested in the camera when they first entered the classroom and were allowed to play a bit with it, but as the lesson started and they got engaged in the classroom interaction, no visible signs that the children paid attention to the camera were observed. The videotaped interaction is transcribed according to the following principles: 1) the interaction is transcribed word–for-word; 2) pauses are not marked; 3) the interaction is transcribed into written language conventions (with punctuation marks, spelling conventions, etc.); and 4) brackets are used to indicate whether something is said in a specific manner [in a loud voice; mumbling]. These principles of transcription are pragmatically elaborated in relation to the purpose of the study. As focus is restricted to the official classroom interactions and verbal utterances made of the children and the teacher during the analysed literacy activities, in order to explore if they can be understood containing deliberative qualities, I argue that the above principles of transcription fulfil its purpose. In a word-for-word transcription, where pauses are not marked, it is possible to analytically discern plurality in views and verbal evidence of having listened to each other, of having reached consensus and of having questioning authorities, which are the main analytic foci in the analysis of deliberative qualities in the interaction (see next section, Analysis).

The analysis of the transcribed material has been conducted in two steps. In the first step, Englund’s deliberative criteria have been used as analytic foci in order to establish whether the interaction could be understood as comprising deliberative qualities (2000). Hence, the deliberative criteria were operationalized into the following four questions that guided the analysis: a) Is there a plurality of different views confronting one another and are arguments for these different views present? b) Are the children and the teacher showing each other respect and do they listen to each other? c) Are there elements of will-formation and a will to reach consensus present? d) Can authorities or traditional views be questioned?

In the second step, I chose some examples of deliberative qualities in the interaction, identified in the first step of the analysis, which are representative of the transcribed material as a whole.

In this section I present the results of the analysis in four parts, each representing one deliberative criterion.

The occurrence of plurality in opinions and views in an interactional situation is essential if the interaction is to be understood as having deliberative qualities. In the analysed literacy activities, children express their different opinions concerning the text’s form and content constantly while they write and revise their collective story. This can be seen from the very beginning of the discussion:

Example 1 shows how the children immediately start expressing their different views on what animal the story should be about, views that offer different answers to the first question of the Makete Method. Worth noticing is that the children’s responses bring in plurality to the interactional situation (noted above). When the teacher says in line 1 that “we should write such a story today,” she refers to earlier literacy activities in which they have collectively written stories together. In the first grade they collectively wrote stories every week and on those occasions they constructed a routine for their literacy work (cp. Tanner, 2014), namely that one child at a time contributed one sentence to the common story. When the teacher gives the word to Jamal in her first utterance, this can also be understood as a subtle way to install the literacy routine that they have used many times before in this particular collective interactional work, in which Jamal is supposed to answer to the first question, forming the story’s first sentence. However, since the children respond differently, as we can see in the excerpt above, they change the text creation process, by which different possibilities are made visible, before agreeing on a specific suggestion. Several minutes later, the teacher tries to employ their literacy routine again, but this time more directly:

| 1) | Teacher: Shall we do like this, that we go the full circle. We start here with you, Jamal, and then we take one question at a time. |

This appeal from the teacher is soon forgotten as the children continue to be vividly engaged in giving suggestions; in other words, the children’s interactional order, in which they come up with different suggestions for every question, is established and lasts through both lessons in which they work collectively with the text. Even though, as in example 1, they do not always give arguments to support their suggestions, they are not asked to do so. Instead, the teacher asks them if they want to take a vote. Voting, as we shall see in more examples below, is used recurrently in these literacy activities as an efficient way to reach consensus when no more opinions are expressed. However, on some occasions during these lessons, the children support their arguments, as in the following case when they are revising a part of the story together:

In the third example we can see how Maja argues that the text needs revision, as it does not hold together content-wise. She points out the lack of logic of there being no one to beg from when it had been stated in an earlier passage of text that all people were out raking their yards. This argument is taken seriously, even though she actually had to point this out three times during their revising activities before being heard. But at this point the teacher and the children start searching for another solution.

Both examples above illustrate the children’s suggestions concerning the content of the story. However, suggestions concerning the formal aspects of the text are also very common during the lessons, especially in the revising part of the process. Sometimes the children also express their opinions concerning the process of their mutual work, which can be seen in the fourth and fifth examples below.

In the first and third example above, we can also see the absence of controlling questions (IRE/IRF pattern); the questions that are asked, not only by the teacher but also by the children, could be understood as authentic (Dysthe, 1996). Thus, the function of the questions in the interaction, in the above example as well as those below, are not controlling, but problem-solving in terms of finding solutions during collective writing and revising. In that way, the children are positioned as already competent writers who can take part in negotiations and discussions on choices in writing. Being positioned as an already competent writer rather than a writer-to-be seems to be an important prerequisite for realising interaction with deliberative qualities, as such interaction ideally should take place among equals (Habermas, 1987; Eriksen & Weigård, 2000; Gutmann & Thompsson 1996; Englund, 2000). When children and their teacher interact in order to solve problems together, in this case, collectively writing and revising a story, they are closer to the deliberative ideal of meeting as equals than if the teacher had had the interactional position as transmitter and controller of knowledge in relation to the children – a teacher position often constructed by IRE/IRF.

Finally, the first criterion for deliberation is interdependent with the second, to listen and respect the other parties in the deliberative situation; there is no point in expressing different views and arguments if they are not listened to.

This section deals with the second core criterion for deliberation, which is the presence of respect for the other, not least through listening to each other (Englund, 2000). Being positioned as equals and as already-competent writers in the discussion, as pointed out above, can be understood as the presence of respect for all involved in the interactional situation. Thus, respect for the other can be understood as embedded in the organisation of the interaction, in which the children are recognised as competent writers with the right to participate in the collaborative writing, an interactional organisation that the children actively contributed to. By listening to each other, they showed both respect for everyone’s right to express their opinions as well as respect for each other as persons. There are no diminishing remarks toward anyone’s suggestions, which all examples from the transcripted interactions in this article give evidence for. Even when the children disagree, which they do quite often, they still seem to show respect to one another by listening and by not ridiculing one another.

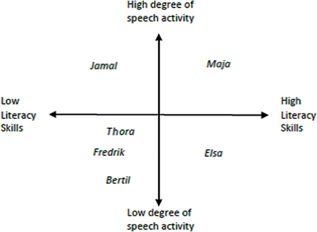

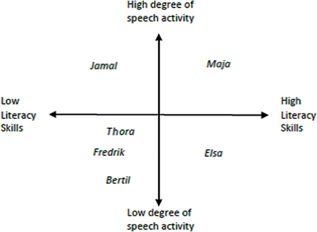

However, even if they listen to each other, some children are more readily listened to than others, which might also mean that they are shown more respect. Some children have to struggle, at times, to get their voices heard. By struggle, I refer to the fact that they occasionally have to come back to a subject that they found important. A suggestion that could be a better argument is not automatically listened to. The six children in the analysed literacy activities, could be placed on a chart with four quadrants showing their position in the discussion in relation to their degree of speech activity and their overall literacy skills:

Figure 1.

Interactional positions in terms of speech activity and literacy competence High degree of speech activity.

The children’s positions in relation to literacy skills in Figure 1 correspond to the teacher’s evaluations of the children’s overall writing skills; the teacher’s evaluations matched the observations I had done during fieldwork in the class for two and half years, during which I also repeatedly read the children’s texts.

As we can see in the figure 1, Maja and Jamal are the most active students during the analysed literacy activities. While Maja has a high literacy competence, Jamal has a lower one. Their high degree of activity is not the only thing that they have in common in the discussion. They are the ones who are sometimes not listened to by the others (the teacher as well as the children) and who have to struggle to make themselves heard at times. As mentioned earlier, in relation to example 3, Maja has to make her suggestion to revise the text three times, a suggestion she supports through arguing that the story lacks logic, before her suggestion is taken seriously. That Maja is not listened to is not because her suggestion is viewed as not valid or solid; nobody presents any counter-arguments. On the contrary, as soon as she is heard, nobody has any objections to her suggestion and it is recognised as a good (best) argument.

Jamal, who does not have Swedish as his mother tongue, misunderstands the Swedish word tigger (to beg) and thinks the word refers to the Swedish word tiger (tiger). He tries three times to communicate that there is something wrong with the text before anyone understands that he has mistaken the word tigger for tiger. Maja and Jamal, who are the most speech-active children in the literacy activities analysed, are also the children who meet the most resistance. Still, Maja and Jamal are those who influence the story most on account of their high activity and many suggestions.

Elsa, on the other hand, who has high literacy competence, but not a high degree of activity during the analysed literacy activities, is the one who is always listened to both by her peers and the teacher, and her suggestions are almost always accepted, which can be seen in example 5 below, when the very same suggestion meets resistance from the teacher when it comes from Maja, but is immediately accepted by the teacher when Elsa supports it.

Those who have the lowest degree of activity are often listened to instantly by the teacher and quite often by the children as well. Thora, who has a low degree of activity and a low literacy competence, is often listened to when she says something and her suggestions are often accepted. If her suggestion is not expressed clearly, she often gets help from the teacher or a classmate. Thus, the teacher takes on an active role as moderator of the interaction, particularly to open up the floor to those children who have a low degree of speech activity and/or have difficulties in formulating suggestions for their story. The teacher’s actions here can be understood as a strategy of creating the preconditions for the participation of all the children and preventing the interaction from “widen[ing] the developmental gap between students”, as the teacher in Tammi’s (2013) study feared would be the result of a similar situation.

The respect shown to a child by the other children and by the teacher, and its degree of influence on the text, is also connected with the power relations within the group; the status a child has in the group matters in relation to the possibility of influencing the text. A child’s possibility to use her/his agency in classroom interaction, in this case, in terms of getting her/his suggestions accepted, seems to be constituted in a complex interplay of degree of activity, competence, and status in the group’s power relations (cf. Janks, 2010).

The third criterion of deliberative communication is the presence of will formation and the reaching of consensus. Consensus could either be strong, meaning that all parties in the deliberative situation finally agree on the best argument, or weak, meaning that all parties at least agree upon what they disagree upon. (Englund, 2000; Habermas, 1987). Elements of collective will formation are present during the interactional processes when they are writing and revising the collective story. The creation of a common story goes through a process of agreement on what the story should be about (the plot), what characters it should contain, how the setting should be depicted, and what words, style, grammar (tense), etc. should be chosen. Even though the way of coming to agreements, consensus, is at times a struggle and the consensus reached is not always strong, as everybody does not agree that the winning solution actually was the best one, the situation could still be interpreted as deliberative, since the teacher and the children all agreed on the procedure for coming to that decision, which made it possible for everyone to accept the suggestion. However, in cases when someone is not happy with a decision, they continue to search for solutions until they can all agree, which is illustrated in example 4 below. During the revision process, the children have the opportunity to reverse an earlier decision that they are not happy with. The teacher summarizes the agreements gradually as the discussion proceeds by asking the students: “What about this?” or, “Is it good like this?”

Some decisions are taken after a child has delivered an argument or after several children and the teacher have discussed something, but it is quite common when they disagree that they decide to vote quite quickly, as in the first example above. Voting seems to be both a joyful activity and an efficient one. Voting is suggested both by the teacher, as in the first example, and by the children. As soon as someone suggests voting, smiles spread from face to face, but voting is also suggested, not the least by Elsa, as we can see in example 4 below, when they seem to be at a dead end – when several suggestions have been expressed and nothing new is brought to the discussion. Hence, voting, as pointed out earlier, becomes an efficient way to reach consensus.

At the very end of the revision process, the teacher asks if they are done and can consider the story finished. The children agree, but want to hear the computer voice reading the story once more. When finished, Maja declares that the sledge needs to have a colour and suggests that it should be red:

Even though all children first exclaimed “Yes!” at the teacher’s question in line one, “Are we done now,” Maja’s suggestion at line 5 becomes the start of a cascade of suggestions about the colour, and the revising process is opened again. In the end, Jamal suggests that it should be in the colours of the rainbow, a suggestion that Maja votes for in the end, since she herself has suggested two different colours for the sledge as we can see in line 5 and line 60. This discussion of colours is one example in which the children come up with different suggestions but do not support these argumentatively. Still, the fact that children change their minds during the discussion, as Maja does, shows that they are influenced by each other’s suggestions. In this case, when Maja votes for Jamal’s suggestion, it even seems that she appreciates the suggestion as the best one, as Jamal is usually not immediately listened to by his peers in the way that Elsa is.

The fourth criterion of deliberative communication concerns the possibility of questioning authorities and traditional views. The children question each other’s suggestions and contributions, usually by referring to a tradition, in this case is a grammatical tradition dealing with the correct way of constructing sentences and texts, such as not having unnecessary repetitions of nouns and pronouns. Challenging traditional views and/or challenging authorities is rare in the analysed literacy activities. However, there is one instance when a child challenges both traditional views and authorities (the teacher). This happens right after Maja’s suggestion, that it is not logical that there are no people to beg from, since lot of people were raking their yards several lines up (see example 3), is heard. The teacher turns to Maja and asks her for a solution, and then the following happens:

The children are usually not told what they can or cannot write, except for this instance. We can see in the lines 5, 7 and 8 that the teacher has objections to Maja’s suggestion. The teacher claims that her objections are on procedural grounds; they cannot change the story at this time. The question on what pupils should be allowed to deliberate and decide upon has been dwelt upon in earlier research: Tammi claims that opening up the floor for pupils’ deliberative initiatives is a crucial challenge for deliberative communication in educational settings (2013). However, we can also see in line 10 that Maja does not consider the teacher’s procedural argument as solid, pointing out that changing is the activity they are engaging in. Maja does not hide her irritation. The other children seem to be exhilarated by Maja’s somewhat bold suggestion that the main character should be stealing. Bertil, in line 3, who has a low degree of activity in the discussion, says “yes” spontaneously. It seems as if Maja’s challenging the norms of the adult world and the school, is exciting for some of the children. When Elsa suggests that Blixten could steal a vase instead, in line 14, the teacher instantly accepts her suggestion, even though she had argued against it a moment earlier when Maja suggested it. In this example, we can see that the children can challenge authorities, the teacher in this case, as Maja does when she directly questions the teacher’s objection of her suggestion. Interestingly enough, we can see that Maja meets resistance when she challenges the school norms with her suggestion, while Elsa, who just slightly revises Maja’s suggestion, does not. Even Bertil’s wish is overlooked by the teacher, despite the fact that he has a low activity degree and his suggestions are therefore usually accepted. But this time he also meets resistance, even if not in such a direct manner as Maja does. This example shows in a clear way how the child’s status in the group also affects the teacher’s response. Elsa is given freedom to create (even though she also challenged norms), while Maja is denied that freedom. Elsa’s suggestions are, as pointed out earlier, almost always accepted by all other children and the teacher. This is not the case for Maja.

Is it reasonable to say that the interaction studied can be understood as a lived democracy in the Deweyan sense? And, if we think so, could this form of democratic life be recognised as having deliberative qualities? We have seen that the participants are allowed and welcomed to express their different views, while at the same time, they are expected to show each other mutual respect, which they do. Expressing different views on the creation and revision of their story is done constantly during the two interactional sessions analysed. Is that sufficient to meet the first and second criteria? It has also been shown that most of the time the children do not discuss their different suggestions, but instead go directly to voting when there are disagreements. That could be seen as ironic from the perspective of the deliberative tradition, in which part of the motivation for deliberation is that voting is not enough (Englund, 2000; Habermas, 1987; Gutmann & Thompsson 1996). The latter is, of course, a statement that perhaps needs to be understood at a societal level rather than at a group level. One possible conclusion is, however, that expressing one’s views without further deliberation is a rather weak deliberative situation.

Still, as I have suggested in the analysis above, the teacher and the children agree on the procedure for reaching consensus when there are many suggestions on the table, which makes it possible for everyone to accept the decision, even though the participants do not always agree that the suggestion chosen is the best one. However, there are also instances when the children change their minds upon hearing suggestions from other children, as pointed out in relation to example 4, when Maja finally votes for Jamal’s suggestion and thereby drops her own two previous suggestions. Hence, even though the suggestions are not supported by arguments, they at times influence the other participants in the discussion. From this I draw the conclusion that the interaction analysed contains deliberative qualities, especially in relation to criteria a, b and c, and therefore, there is a substantial potential for developing the practice even further in a deliberative direction, in which suggestions could be supported more frequently by arguments. In this context, it is also important to remember that the teacher, in this study, was not asked to organise her teaching in a deliberative form, as the teachers in the earlier mentioned studies on designed deliberative communication in classrooms (Forsberg, 2011; Thyberg, 2012; Andersson, 2012; Tammi, 2013). Naturally, if the teacher in this study had been instructed to ask for the children’s arguments along with their suggestions, the result might have been different. However, evaluating designed deliberative teaching is not the aim of this study, as I wanted to analyse the interaction of everyday literacy activities to discern if they comprised deliberative qualities. Tammi claims that “even though most pupils probably have not yet developed the skills for democratic deliberation, these skills can still be practiced” (2013, p.75). My study confirms that children can practice deliberative skills even when those skills are not formally taught. If a deliberative education becomes too instrumental, there is a risk that the children are not positioned as already-competent participants, in this case, already-competent writers, which I see as an important prerequisite for realising deliberative communication among equals in the classroom. As mentioned earlier, Liljestrand shows in his study that the fact that the pupils are not being positioned as knowledgeable citizens but as citizens-to-be in classroom discussions drains the classroom interaction of its democratic potential (2002). In the analysed literacy activities, the teacher does not teach the children how to write a story, but asks them how they want to write it. I would say that it is exactly when the teacher asks the children those authentic questions that democratic moments are created, when the children get the opportunity to engage in choosing. In this context it is also worth noting that the IRE/IRF pattern with its controlling questions is quite absent in the analysed literacy activities. Another important prerequisite for realising deliberative qualities in the analysed interaction is when the teacher gives room for the pupils’ initiative to negotiate the content and form of the story. The teacher does not enforce the form of communication she first initiates, that each pupil ought to contribute one answer/sentence at a time, but accepts the negotiating process initiated by the children.

I have also pointed out how power relations among the children, and between the children and the teacher, create a situation in which some children are more privileged by being taken seriously and having their suggestions accepted while others have to struggle more – a situation in which the participants cannot be described as equals either in terms of activity, competence or status. These three aspects interplay in the process of collective-will formation, but not in a foreseeable way. The two children that have to struggle most to be heard, Maja and Jamal, are also the children who in the end get most of their suggestions accepted, as they continue to be active even after they have met resistance. Not giving up when other people do not listen to you seems a relevant democratic experience, as most situations in the world are not a peaceful meeting among equals sharing a rational argument.

Finally, I would say that the set of deliberative criteria used in the article (Englund, 2000) has pragmatic value as normative democratic guidelines for educational practice, if they are used wisely: that is if they are used as reflective tools for teachers and students for evaluating their interactional practice rather than as objects of learning. As reflective tools they can help by recognising the opportunities and challenges of realising democratic experiences in classroom. Thus, reflecting on the mutual practice in order to improve it can be done by equals, while teaching deliberative skills as an object of learning comprises the risk of positioning the students as not-yet competent participants in interaction – which might hinder the realisation of deliberative qualities in classroom interaction.

Almgren, E. (2006). Att fostra demokrater: om skolan i demokratin & demokratin i skolan. Uppsala: Uppsala universitetsbibliotek distributör.

Andersson, K. (2012). Deliberativ undervisning – en empirisk studie. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.

Barton, D. (1994). Literacy: An introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford: Blackwell.

Barton, D., Hamilton, M. & R., Ivanič (Eds.). (2000). Situated literacies: reading and writing in context. London: Routledge.

Biesta, G. (2007). Beyond Learning: Democratic Education for a Human Future. London: Routhledge.

Blikstad-Balas, M. & Sørvik, G.O. (2015). Researching literacy in context: using video analysis to explore school literacies. Literacy, 49(3), 140–148.

Boman, Y. (2002). Utbildningspolitik I det andra moderna. Om skolans normativa villkor. Örebro Studies in Education 4: Örebro universitet.

Cazden, C. B. (1988). Classroom Discourse: the Language of Teaching and Learning. Portsmouth: Heinemann cop.

Dahlstedt, M. (2000). Demokrati genom civilt samhälle? Reflektioner kring Demokratiutredning sanningspolitik. Statsvetenskaplig tidskrift, 4, s. 289–310.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. Radford VA: Wilder Publications, LLC.

Englund, T. (2000). Deliberativa samtal som värdegrund – historiska perspektiv och aktuella förutsättningar. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Englund, T. (2006). Deliberative Communications: a Pragmatist Proposal. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38(5), 503–520.

Eriksen, E. O. & Weigård, J. (2000). Habermas politiska teori. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Ewald, A. (2007). Läskulturer. Lärare, elever och litteraturläsning I grundskolans mellanår (p. 29). Malmö Studies of Educational Sciences No.

Gutmann, A. & Thompson, D. (1996). Democracy and Disagreement. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Forsberg, Å. (2011). Folk tror ju på en om man kan prata. Deliberativt arrangerad undervisning på gymnasieskolans yrkesprogram. Karlstad University Studies.

Habermas, J. (1987). The theory of communicative action. Boston: Beacon Press.

Heath, S.B. (1983). Ways with Words: Language, Life and Work in Communities and Classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

Hermansson, J., Karlsson, C. & Montgomery, H. (2008). Samtalets Mekanismer. Malmö: Liber.

Hultin, E. (2007a). Deliberativa samtal i skolan – utopi eller reell möjlighet? In E. Englund (Ed.) Utbildning som kommunikation – Deliberativa samtal som möjlighet (p.317–335). Göteborg: Daidalos.

Hultin, E. (2007b). Dialogiska klassrum eller deliberativa klassrum – spelar det någon roll? En jämförelse mellan två normative positioner i det samtida talet om skolans demokratiuppdrag. In E. Englund (Ed.) Utbildning som kommunikation – Deliberativa samtal som möjlighet (p.381–397). Göteborg: Daidalos.

Hultin, E. & Westman, M. (2013a). Digitalization of early literacy practices. Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal, 4(2), 1005–1013.

Hultin, E. & Westman, M. (2013b). Literacy teaching, genres, and power. Education Enquiry, 4(2), 279–300.

Hultin, E. & Westman, M. (Eds.). (2014). Att skriva sig till läsning – erfarenheter och analyser av det digitaliserade klassrummet. Malmö: Gleerups.

Janks, H. (2010). Literacy and power. London: Routledge.

Jönsson, K. (2007). Litteraturarbetets möjligheter. En studie av barns läsning I årskurs F-3. Malmö: Malmö Studies in Educational Sciences No 33.

Kant, I. (1784/1992). An answer to the question: What is Enlightment? In P. Waugh (Ed.), Critique of Pure Reason. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Larsson, K. (2007). Samtal, klassrumsklimat och elevers delaktighet - överväganden kring en deliberativ didaktik. Örebro Studies in Education 21: Örebro universitet.

Lewin, L. (2003). Folket och eliterna – trettiotre År efteråt. I: Gilljam, M. & Hermansson, J. (red.), Demokratins mekanismer. Malmö: Liber.

Liljestrand, J. (2002). Klassrummet som diskussionsarena. Örebro Studies in Education 6: Örebro universitet.

Lindblad, S. & Sahlström, F. (2000). Klassrumsforskning – en översikt med fokus på interaktion och elever. In J. Bjerg (Ed.), Pedagogik. Stockholm: Liber.

Mehan, H. (1979). Learning Lessons: Social Organization in the Classroom. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Papastephanou, M. (2010). Utopia and Political Re-education. In Murphy M. & Fleming T. (Eds.). Habermas, Critical Theory and Education. New York: Routledge.

Roth, K. (2001). Democracy, Education and Citizenship – Towards a Theory on the Eduacation of Delberative Democratic Citizens. Doktorsavhandling. Stockholm: Stockholm Institute of Educational Press.

Schmidt, C. (2013). Att bli en sån’ som laser. Barns menings- och identitetsskapande genom texter. Örebro: Örebro Studies in Education No 44.

Sinclair, J. & Coulthard, R. (1975). Towards an Analysis of Discourse. London: Oxford University Press.

Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education]. (2011). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and the leisure-time centre 2011. Stockholm: Fritzes.

Skoog, M. (2012). Skriftspråkande i förskoleklass och årskurs I. Örebro: Örebro studies in Education No 33.

Street, B. (1995). Social Literacies: critical approach to literacy development, ethnography and education. London: Longman.

Tammi, T. (2013). Democratic Deliberations in the Finnish Elementary Classroom: The Dilemmas of Deliberations and the Teacher’s Role in an Action Research Project. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 8(1), 73–86.

Tanner, M. (2014). Lärarens väg genom klassrummet: Lärande och skriftspråkande i bänkinteraktioner på mellanstadiet. Karlstad University Studies 2014:27. Karlstad universitet.

Thyberg, A. (2012). Ambiguity and Estrangement: Peer-Led Deliberative Dialogues on Literature in the EFL Classroom. Kalmar: Linnaeus University Press.

Utbildningsdepartementet [Ministry of Education and Research]. (2010). Skollagen, SFS 2010:800 [The Swedish Education Act, SFS 2010:800]. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

1These criteria were first published in Swedish by Englund in 2000. For this article, I have used the English translation of the criteria from the article, Deliberative Communications: A Pragmatist Proposal (Englund, 2006).

2Biesta emphasizes that these two can be complementary; as students learn about, for instance, governmental forms in civics, they are invited to do so by participating in democratic working forms (2007).

3The text in table 2 and the texts in all examples in the article are translated from Swedish into English.