Introduction

Writing plays a central role in teacher education. Among other things, it comprises a key mediating tool in the processes of enhancing students’ academic learning, and their development towards becoming professional practitioners (Klemp et al., 2016; Macken-Horarik et al., 2006; Nilssen & Solheim, 2012; Wittek et al., 2015). Much of the writing research conducted in teacher education has examined students’ perspectives and experiences related to working with genres of writing that are formally assessed, such as academic papers and exam portfolios (Arneback et al., 2017; Wittek et al., 2017), or types of reflective writing (Hume, 2009; Mortari, 2012). In most teacher education programs, however, there are many other forms of writing activities that take place during classes, lectures, and seminars which are not formally assessed or constitute components of formal coursework. Such writing activities have rarely been systematically analyzed, and consequently there is limited knowledge about their roles and functions in teacher education classrooms.

In this study, we explore in-class writing activities used by a multidisciplinary group of teacher educators at one teacher education institution. We ground our investigation in a New Literacy Studies (NLS) framework, in which literacy is understood as something people do with language, essentially social in nature and embedded in interaction between people (Barton & Hamilton, 1998). Moreover, within NLS, the concept literacy events describes activities where types of literacy – such as writing, speaking, reading – play a role, often in combination (Barton & Hamilton, 2000). Based on this understanding, we conceptualize the writing activities we analyze as literacy events to gain a better understanding of the nature of the writing activities the teacher educators use in their teaching, including aspects such as framing and key features and, in particular, perspectives on writing the activities may reflect. To this end, we analyze fifteen writing prompts and fieldnotes from observations of fifteen literacy events in which writing was at the center and ask: What perspectives on writing are reflected in the writing activities in these literacy events?

By investigating in-class writing activities as they unfold in the literacy events, we wish to contribute knowledge to a relatively under-researched area across educational contexts (see, e.g., Blikstad-Balas et al., 2018; Moon et al., 2018). Gaining a clearer insight into teacher educators’ uses of and perspectives on in-class writing activities is pivotal to understand the role of such activities in the facilitation of students’ development into professional practitioners (Helstad et al., 2017; Solbrekke & Helstad, 2016). Thus, we seek to expand existing knowledge about the roles and functions of writing activities in teacher education classrooms.

Previous research

A sizable amount of literature examines student perspectives on writing – and learning to write – in teacher education. Several studies show how students struggle with mastering the writing conventions of the different disciplines they encounter (Arneback et al., 2017; Erixon Arreman & Erixon, 2017). Arneback and colleagues (2017), for instance, explain how novice students often experience their first period at university as “something of a shock, since the ideals and demands of writing and reading are new to them” (p. 281). Relatedly, Jonsmoen and Greek (2012) found that students had difficulties interpreting assignment instructions, formulating research questions, synthesizing content and structuring the text (p. 15). In a similar vein, studies that have investigated the dual orientation of writing in teacher education towards what Macken-Horarik et al. (2006) label the professional and academic domains highlight that students often find it challenging to balance or combine the different discourses of those domains (Erixon Arreman & Erixon, 2017; Northedge, 2003).

While the studies outlined above focus primarily on students’ challenges in learning the writing conventions and discourses of teacher education, others have explored the role of writing as a learning tool. Researchers have argued that engaging in reflective practice may enhance students’ academic reflection and mediate disciplinary learning (see, e.g., Gere et al., 2018; Helstad et al., 2017). Reflective practices may also augment students’ thinking about professional practice and strengthen their participation in their own learning processes (Hume, 2009; Mortari, 2012; Neff et al., 2012). Writing can also help bridge the gap between the disciplinary and practice fields and help students see the links between the two (Nilssen & Solheim, 2012). Similarly, Solbrekke and Helstad (2016) argue that writing is essential in helping students “connect to their future roles as teachers” (p. 971).

Research into the use of writing activities in higher education classrooms claims that such activities hold potential as a pedagogical learning tool, especially if they are systematically integrated into teaching practice (Leon, 2020; Neff et al., 2012) and ask students to “reflect on their current understandings, confusions and learning processes” (Bangert-Drowns et al., 2004, p. 51). However, a study from Norwegian lower secondary school found that such activities commonly focused on developing content knowledge (Blikstad-Balas et al., 2018).

Finally, research has also explored teacher educators’ approaches to working with students’ writing. The teacher educators in a study by Ofte and Otnes (2022) emphasized the dual purpose of writing as a tool for enhancing students’ disciplinary learning and professional development. Other studies from higher education have highlighted how teachers’ approaches to writing instruction are most often student-centered and process-oriented and involve student interaction and group work (Solbrekke & Helstad, 2016; Wittek et al., 2017). Studies have also identified and problematized limitations in teachers’ metalanguage about writing in professional education programs (see, e.g., Greek & Jonsmoen, 2016; Jonsmoen & Greek 2012). In their study, Arneback and colleagues (2017) emphasized the importance of teacher-student metacommunication about academic writing within and across disciplines in teacher education, in terms of students’ “disciplinary literacy in academia and future professional needs” (p. 281).

The research presented above provides insight into different aspects relating to writing in teacher education. However, as our overview also makes clear, more research into the kind of writing activities that teacher educators initiate in their classrooms is needed. Blikstad-Balas et al. (2018) also argue that there is a need for systematic investigations into “what kind of writing that takes place when such opportunities [writing during lessons] are provided” (p. 120). With this study, we seek to contribute to a deeper understanding of the writing activities included in the literacy events we investigate and the perspectives on writing they may reflect. In so doing, we hope to contribute a more comprehensive understanding of the roles and functions of writing in teacher education.

Theoretical underpinnings

Grounding our investigation within a sociocultural paradigm (Vygotsky, 1986), we draw specifically on the New Literacy Studies (NLS) perspective of literacy as social practice. In this perspective, literacy is understood as something that people do with language (Barton & Hamilton, 2000). Moreover, all literacy activities, such as writing, reading, and speaking, are seen as essentially social in nature and located in the interaction between people, always situated and constituting parts of broader social and cultural practices (see, e.g., Barton & Hamilton, 2000; Gee, 2015). Consequently, writing is also particular to specific social domains (Gee, 2015). In the domain of teacher education, writing entails, among other things, the ability to “negotiate tasks relevant to school teaching” (Macken-Horarik et al., 2006, p. 244) such as lesson plans and evaluations, but also tasks relevant to academic learning, such as formal texts.

Within the NLS framework, literacy events are central to the exploration of the social nature of literacy. Barton and Hamilton (2000) define them as observable activities “where literacy has a role” (p. 8). This opens for a wide understanding of the concept because it shows how, as Blikstad-Balas (2013) argues, literacy events can be more than explicit activities “where one reads or writes with a defined goal” (p. 25). In educational contexts, she continues, learning is often the overarching goal of such activities, rather than reading or writing per se (Blikstad-Balas, 2013). This also implies that in literacy events, various types of literacy activities can work together for learning purposes.

Relatedly, Barton and Hamilton (2000) explain that literacy events arise from and are shaped by literacy practices – i.e., the ways people understand, think about, speak about, and use literacy in different contexts (p. 8). Thus, writing can be examined not only as text, but also in terms of the literacy practices and perspectives that produce the texts. Therefore, conceptualizing the writing activities as literacy events seems particularly useful to our investigation because it opens for exploring the nature of the writing embedded in the events as well as the potential perspectives on writing which those activities may reflect.

Also central to our investigation are perspectives on writing proposed by Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC), a theoretically framed pedagogical approach to writing instruction in higher education (see, e.g., Russell, 2002). A core pillar within WAC is the notion that student learning happens through – and with – writing (cf. Emig, 1977). WAC is grounded in two theoretical approaches to writing. McLeod (1987) argues that these are not mutually exclusive, but instead exist on a continuum “from expressive to transactional writing” (p. 19). The first approach, writing to learn, is rooted in constructionist theories on learning, seeing the individual’s cognitive processes as central to knowledge construction (Emig, 1977). Writing, then, becomes a way of thinking. Central here are writing-to-learn activities, which Bean (2011) defines as “thinking on paper” (p. 121). Exploratory and reflective in nature, such activities aim to develop students’ subject knowledge and content area literacy (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008).

The second theoretical approach undergirding WAC is learning to write, which is closely associated with writing in the disciplines (WID). Drawing on sociocultural learning theories, it emphasizes “the contextual and social constraints of writing” (McLeod, 1987, p. 20). As such, WID puts “greater attention to the relation between writing and learning in a specific discipline” (Russell et al., 2009, p. 395) than WAC. Hence, within a WID perspective, learning to write constitutes a way to create, disseminate and evaluate knowledge in specific disciplines, and develop students’ disciplinary literacy (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). Learning-to-write activities are closely associated with WID. These are designed to introduce students to – and help them practice and develop – the communication skills, genres, and writing conventions characteristic of specific disciplines (Deane & O’Neill, 2011; Palmquist, 2020). In the context of teacher education, the WID perspective is quite complex because writing draws on many disciplines, from sciences to the arts, as well as the practice field. Thus, what disciplinary writing looks like in teacher education might not be entirely straightforward (Erixon & Josephson, 2017).

In addition to the disciplinary diversity embedded in teacher education programs, there is another element that warrants the introduction of a third category of writing activities called writing-to-become-teachers activities (Ofte & Otnes, 2022). These are specifically geared to helping students develop professional literacies (Macken-Horarik et al., 2006) through exploring written discourses, genres and conventions that are relevant to their future careers as teachers.

Together, the three perspectives outlined above highlight approaches to writing in educational contexts. However, it must be mentioned that Carter et al. (2007) criticize the perceived separation between the writing to learn and learning to write perspectives, arguing that it limits the learning aspect of learning-to-write activities to a focus on written conventions and discourses. This criticism points to a more complex dynamic between different forms of writing, which we return to in our analysis and discussion.

Methods and material

Research context and participants

This study is part of a larger qualitative project which investigated teacher educators’ literacy practices in working with student writing. In line with the qualitative design of the larger project, the aim of this study was not to look for representative practices, but rather to analyze the characteristics of some literacy practices as observed in classroom contexts.

Eight teacher educators – three from languages, another three from social science, as well as one from the arts and one from natural science – participated in this study. They all work at the same teacher education institution. It should be noted that no separate writing courses are offered at this institution; all writing instruction is integrated into the individual disciplines. This means that the students do not receive any explicit writing instruction other than what their subject courses provide.

The participants were recruited to the larger project based on their participation in a three-day interdisciplinary writing seminar which focused on helping faculty in higher education integrate effective writing practices into their teaching to facilitate student learning. At the end of the writing seminar, the participants were asked if they were willing to participate in a research project, and eight volunteered. Their participation in the writing seminar, and their interest in participating in the research project, could indicate that they were particularly interested in student writing. We will consider the implications this might have in our discussion. Prior to their participation in the larger project, the teacher educators received information about its nature and purpose, and a letter of consent informing them of their rights as research participants. They have also had the opportunity to read and comment on drafts of this article throughout the writing process.

Certain aspects related to the transparency of the study should be mentioned. Firstly, the first author conducted the larger research project, including this study. She recruited the participants, and collected and analyzed the data material. However, both the analysis and the findings were discussed with the second author. Secondly, the first author works at the institution where the research was conducted. Thus, she and the research participants are colleagues. Finally, she also co-organized the writing seminar from which the participants were recruited.

The first author’s familiarity with the institution and the seminar, and her collegial relationship with the research participants, reflect her status as an insider in the research context. As an insider, she has her own personal experience of being a participant in the research context, and this experience might influence her interpretations (Kvernbekk 2005, p. 43). Consequently, her insider status necessitated what Alvesson and Sköldberg (2018) labels reflexivity throughout the research process. This implies that she had to continuously consider how her knowledge of and experiences with writing in teacher education could influence her perceptions of the writing activities she observed, and shape her interpretation of the writing prompts.

Data generation

The data material, which was collected between September 2019 and March 2020, consists of fifteen writing prompts initiating the writing activities, and fieldnotes from classroom observations of fifteen literacy events in which the writing activities took place. Classroom observations were chosen to gain more detailed insight into the type of writing activities the teacher educators initiated, and their use of such activities in classroom contexts. The first author asked the teacher educators to invite her to a session of their choosing where they planned to include one or more writing activities. The teacher educators emailed her the writing prompts and she read through them prior to conducting the classroom observations. Of the twenty observations conducted, five were discarded because they were either duplicates (one teacher educator conducted the same activity twice), or there were anonymity issues (one activity related to an easily identifiable research project). Two observations were excluded because they included types of literacy outside of the scope of this study; in one, the students made illustrations to texts, and in another they wrote sheet music.

It should be noted that no specific definition of “writing activity” was given. As a result, the data material presents emic perspectives on writing activities – they are what the teacher educators themselves understood as working with writing in their classrooms. The material analyzed thus constitutes snapshots from a limited number of sessions in a limited number of courses from two different semesters. Yet, we find that these snapshots represent rich material for investigation given the purpose of our study.

Prior to the observations, the first author developed a semi-structured observation guide (see appendix) which was used to document how the teacher educators introduced, organized, and concluded the writing activities in the literacy events. It was also used to make a note of any additional instructions or information the teacher educators provided prior to or during the writing activity which were not included in the writing prompt. Finally, any reading or speaking activities interwoven with the writing were also noted down. After each observation, the notes were written up as fieldnotes.

During the observations, the first author took the role of a “complete observer” (Cohen et al., 2011, p. 457) and did not engage in what went on in the classroom. Still, it is unlikely that the teacher educators and the students were entirely unaffected by the presence of a researcher. For instance, it could have impacted the students’ level of engagement in the activities and how the teacher educators approached the writing activity, in that they could have presented it in a way that they imagined the researcher would deem acceptable.

Analytical approach

The literacy events we analyzed were integrated into the teacher educators’ lesson plans. None of them were stand-alone writing lessons or part of a generic writing course – as previously mentioned, such courses are not taught at this institution. Furthermore, we identified the literacy events we explored as starting when the teacher educators introduced the writing activity and ending when they summarized the activity and moved on to another topic or concluded the lesson. Finally, as we understand the concept, a literacy event can consist of a single writing activity or several interlinked writing activities. The writing activities may also be combined with other literacy activities.

To gain insight into the types of writing the teacher educators included in their teaching, we first identified and structured key features and aspects of framing in the writing activities. Here we applied open coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2015) to identify patterns and conceptualize the data into categories. We also included any speaking or reading activities intertwined with the writing activities, as well as the length of both the literacy event as a whole and the writing activity to illustrate the ratio between them. In this process, we developed four categories to which we added the key features and framing aspects we identified in the writing activities (Table 1). We conducted a similar procedure on the fieldnotes to identify elements and aspects which could supplement and refine existing findings and categories. Any additional information the teacher educators provided during the literacy events which contributed to framing the writing activities were systematized in two separate categories (Table 2).

The above categorizations helped us compare and contrast the more descriptive features of the writing activities in the literacy events. However, we were also interested in identifying the more overarching types of writing they included, which could help illuminate potential perspectives on writing as educational practice in teacher education classrooms. By “more overarching” we refer to whether the writing activities seemed geared to writing-to-learn, learning-to-write or writing-to-become-teachers. As described in the theory section, these categories attempt to capture the overall purpose of what writing is used for in different educational contexts. Drawing on existing literature (e.g., Bean, 2011; Deane & O’Neill, 2011; Ofte & Otnes, 2022; Palmquist, 2020), we placed activities that seemed process-oriented and explorative in nature in the writing-to-learn category. In the learning-to-write category, we placed activities that appeared more focused on learning writing strategies, textual features, and different types of genre skills. Activities that specifically focused on developing and practicing professional skills and genres that teachers need, or the modeling of activities and approaches to writing that the students might use in their own teaching later, were placed in the writing-to-become-teachers category. As noted in the literature (Carter et al., 2007; McLeod, 1987), these categories might best be conceived as overlapping rather than mutually exclusive. We also found this to be the case in our empirical material. When we identified activities that included more than one perspective, we decided to link the writing activity to the other relevant category or categories, and not only the one we found to be most prominent in the activity. We return to the implications of such an overlap in our discussion.

Analysis

We start this section by briefly presenting the key features and aspects of framing that we identified in the writing activities, before we provide our analysis of the overarching perspectives on writing that we found.

Key features of the writing activities in the literacy events

As Table 1 illustrates, three key features stood out in these writing activities. First of all, they were generally relatively short, lasting between one and ten minutes, with a few exceptions. Moreover, the writing activities generally took up little time in the literacy events overall (see Table 1): For example, while literacy event 2 lasted 45 minutes, students wrote for only four minutes. In the remaining 41 minutes, students engaged in various speaking and reading activities linked to or based on their writing. This draws attention to the second key feature, namely that the writing activities were not separated out as isolated acts in these literacy events, but instead they were intertwined with other literacy activities.

Relatedly, as Table 1 shows, the third key feature illustrates how all the writing activities in the literacy events were interwoven with interaction of some sort, for instance through collaborative writing (1, 4, 8),1 or group talk based on the writing produced at various stages in the literacy event (12, 14, 15). The teacher educators also often engaged with the students both during and after the writing activity, for instance by discussing the content of the students’ writing. The emphasis on interaction and collaboration in these literacy events highlights the social nature of the writing activities. It also suggests that these teacher educators hold a process-oriented and student-centered approach to writing, and see writing as a mediating tool in the students’ learning processes.

| Length of literacy events | Length of writing activities in the literacy events | Individual or collaborative writing in the literacy events | Other literacy activities in the literacy events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 mins | 10 mins | Collaborative | Reading, speaking |

| 2 | 45 mins | 4 mins | Individual | Reading, speaking |

| 3 | 15 mins | 3 mins | Individual | Speaking |

| 4 | 30 mins | 20 mins | Collaborative | Speaking |

| 5 | 10 mins | 3+5 mins | Both | Speaking |

| 6 | 8 mins | 5 mins | Individual | Speaking |

| 7 | 6 mins | 3 mins | Individual | Speaking |

| 8 | 15 mins | 10 mins | Collaborative | Speaking |

| 9 | 13 mins | 10 mins | Individual | Reading, speaking |

| 10 | 60 mins | 40 mins | Collaborative | Reading, speaking |

| 11 | 5 mins | 1 min | Individual | Reading, speaking |

| 12 | 120 mins | 15 + 15 + 15 + 15 mins | Individual | Reading, speaking |

| 13 | 10 mins | 2 mins | Individual | Reading, speaking |

| 14 | 25 mins | 3+3 mins | Individual | Reading, speaking |

| 15 | 120 mins | 10 + 10 + 10 + 10 mins | Both | Reading, speaking |

The teacher educators’ framing of the writing activities in the literacy events

Table 2 shows that, in terms of framing, the teacher educators explained what the students were going to do in the writing activities, from accessing ideas or prior knowledge (3) to reflecting on what they had learned in class (7), justifying didactic choices (2), or designing writing activities for classroom use (4). This suggests that, overall, the teacher educators had clear intentions about what the students were going to do in the writing activities and, importantly, these were communicated to the students (apart from literacy events 9 and 11 where no such information is given). At the same time, there was limited metacommunication about the purposes of the writing activities beyond the concrete teaching situation in which they took place. We will return to this point in our discussion.

Furthermore, Table 2 also illustrates that the actual writing the students were asked to do was commonly framed as informal “thinking pieces” (Bean, 2011, p. 245). For instance, the students wrote different forms of notes such as free associations (3, 5) and summary sentences (7), and they also formulated questions (1), created lists (2), and answered questions (12, 15). Thus, these writing activities seem geared to provide opportunities for students to explore ideas and develop various forms of disciplinary content knowledge, in formats that can be used successfully across disciplines in teacher education.

| The teacher educators’ explanations of the writing activities | What do the students write? | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preparation for writing exam assignment | Suggestions, questions, notes |

| 2 | Justify didactic choices | List of justifications |

| 3 | Access previous knowledge, experiences | Free associations |

| 4 | Design writing activities for use in their own teaching | Writing activities |

| 5 | Access previous knowledge, experiences | Free associations |

| 6 | Access ideas | Free writing |

| 7 | Reflect on session’s content, own learning | Summary sentences |

| 8 | Connect to topic | Fairy tale titles |

| 9 | Not stated | Introductions to fairy tales |

| 10 | Interpretation of primary sources | Answer questions |

| 11 | Not stated | Notes to self |

| 12 | Analyze a research article | Answer questions |

| 13 | Reflection on text | What comes to mind |

| 14 | Reflection on text | What comes to mind |

| 15 | Text analysis | Answer questions |

Perspectives on writing in teacher education

As a way of moving from the aspects of framing and key features outlined above to identifying the more overarching perspectives on writing embedded in these literacy events, we placed each writing activity in one or more of the categories learning-to-write, writing-to-learn, and writing-to-become-teachers. Below, we present the perspectives and illustrate them with sample writing activities from the data material.

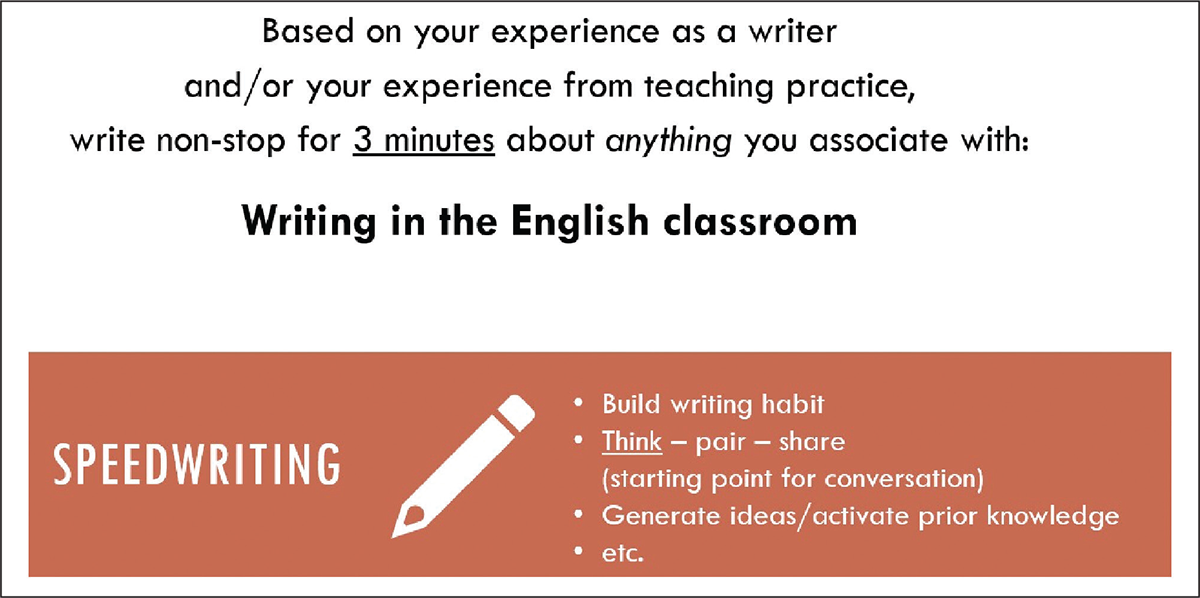

Writing to learn: Thinking and learning

Our analysis shows that, in thirteen of the fifteen literacy events, the writing was geared to sparking students’ thinking about the lesson’s content. This suggests a focus on using writing to develop students’ content area literacy (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). In Example 1, for instance, they were asked to note down their immediate thoughts about a particular statement, based on personal experience. Similarly, in Example 2, the students were explicitly encouraged to utilize their own experiences as student writers to help them retrieve prior knowledge and generate ideas about the topic, first individually and then in groups. Other writing activities had a slightly different focus, such as asking the students to summarize the topics they had talked about in the lesson or reflect together on the purpose of a paragraph in a research article.

|

Reflection task Reflect on the following quote from [course literature]: [Quote]. For one minute, note down whether, based on your own experience, the author’s assertion is valid with respect to KRLE instruction in Norway? |

Example 1. Writing-to-learn activity.2

Common to all the writing activities in this category, then – and in a majority of the data material – was the prominent focus on learning through and with writing. Indeed, these examples illustrate how “thinking on paper” (Bean, 2011, p. 121), both individually and collaboratively, constitutes a central perspective on writing. The teacher educators framed in-class writing as thinking pieces to help develop students’ disciplinary, academic and professional learning, where they think and write – sometimes collaboratively – to discover, develop and clarify ideas, and forge connections between relevant experiences and course content. Yet, as was also referred to in the previous section, the degree to which the use of writing as a learning tool in various contexts was explicitly pointed out by the teacher educators varied considerably.

Learning to write: Exploring knowledge about writing, genres and meta-skills

Even though there are no writing activities in this material that focus explicitly on traditional learning-to-write elements such as paragraph development, citation practices, or argumentation, we argue that six of the fifteen writing activities still contained a learning-to-write perspective. Two writing activities stand out in this respect. In Example 3, the students read a research article from the course curriculum and answered questions regarding the article’s structure, content and methodology. In Example 4, the students were first introduced to the exam assignment and relevant course literature, and then they were asked to work together in groups and formulate questions, and make suggestions and notes based on their reading of the literature and the national curriculum in preparation for writing the exam at the end of term.

|

You are going to analyze a research article from the course curriculum. You are going to read and write, and there will also be some time to share ideas. The finished product will be handed in as obligatory coursework (2–4 pages), and the submission deadline is 22 January. • What is the research question? • How is theory and previous research presented? • Which methods do the researchers apply? • How is the empirical data presented? |

Example 3. Learning-to-write activity.

These examples illustrate how the writing activities in this category are also concerned with developing students’ disciplinary literacy (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). This is evident in a focus on raising their meta-awareness of and familiarity with skills and practices involved in the process of writing academic texts in the respective disciplines. Interestingly, the activities do not ask them to write such texts, but instead present the opportunity to explore skills and practices relevant to academic writing in higher education in general through engaging in informal writing activities. This illustrates that the disciplinary aspect of the writing in these activities remains largely implicit, as it is not explicitly introduced or discussed. It also suggests that the writing in these activities is facilitated in a similar manner across disciplines, further highlighting a focus on learning writing skills generic to higher education, rather than disciplinary conventions.

By categorizing these activities as learning-to-write even if they contain no explicit writing instruction, we expand this category to include not only traditional writing instruction activities, but also activities that give students the opportunity to recognize or write about writing, presumably as a way of preparing for their own writing. Carter and colleagues (2007) similarly emphasized writing as a way of being socialized into disciplines, which implies that learning to write is not only about acquiring the written conventions and discourses of a field, but also involves gaining insight into various literacy practices which characterize writing in specific disciplines. Building on this perspective, we suggest that these writing activities seem intended to help students explore what goes on in a writing process without focusing on the final textual product. However, the teacher educators did not bring attention to these aspects of the writing activities to any substantial degree.

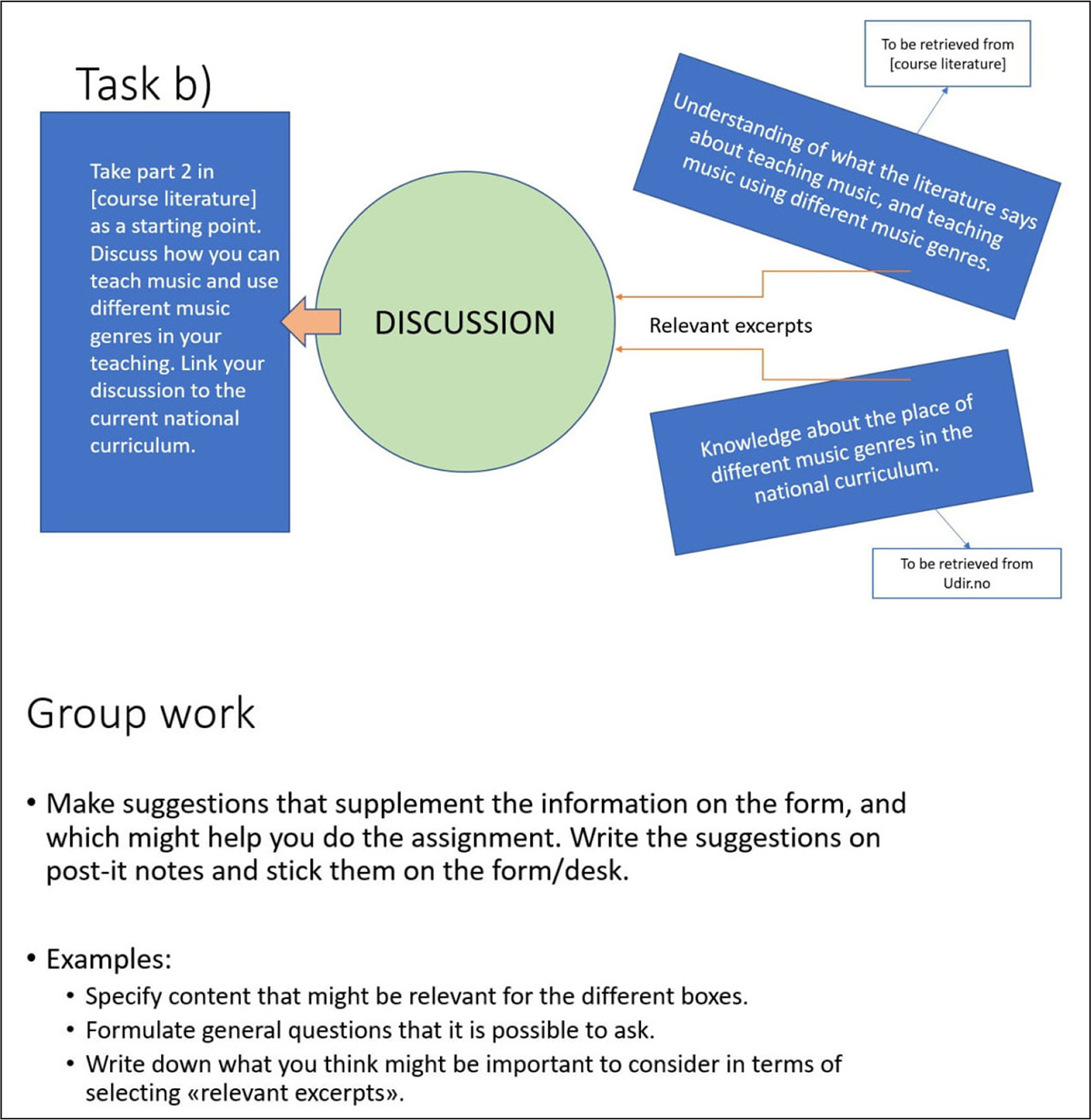

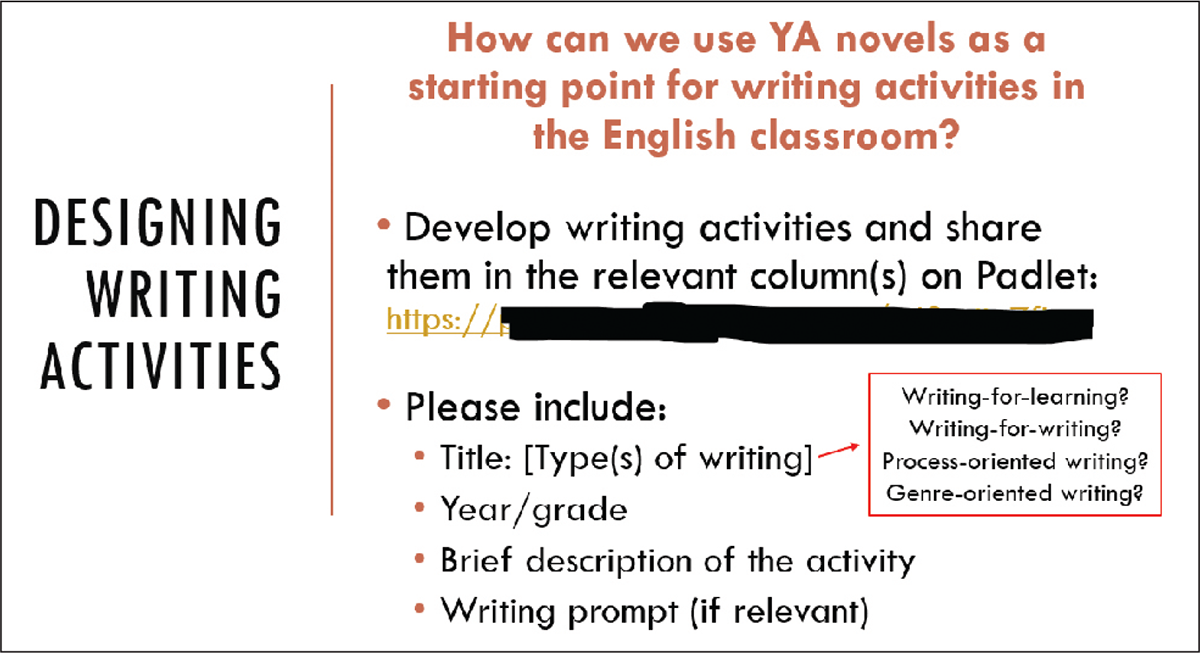

Writing to become teachers: Forming professional practitioners

In five of the literacy events, the writing the students did seemed geared to preparing them for their future roles as teachers. In Example 5, the students were asked to justify didactic choices in their music teaching to a parent, based on their knowledge of music as a discipline and a school subject. In this process, they shared and discussed the content of their writing with their peers. Similarly, in Example 6, the students used their disciplinary knowledge of young adult literature as a starting point for co-drafting writing activities they could use in their practicum, and linked them to specific learning outcomes listed in the national curriculum.

|

Justify didactic choices You are a fifth-grade music teacher who has received an email from a parent: Hello, I am Oliver’s dad, and I see that, lately, you have worked with a theory handout and lectures on Viennese Classicism and that you will watch the film Amadeus during music class tomorrow. I am a teacher at the School of Music and Performing Arts, and I know that many of the students in the class play instruments. Have you been singing or playing music during class, or do you have any plans to do so? Just a small tip: I think many of the students would appreciate it and learn a lot from it. Best wishes, Robert Robertson Spend four minutes and write a list with possible justifications for the teaching that Robert questions. Read to the person next to you. Discuss: What categories in the didactic relationship model do you think the different justifications could be connected to? |

Example 5. Writing-to-become-teachers activity.

These examples illustrate that the writing activities in this category hold a dual focus: they appear to cater to helping students engage with their disciplinary and pedagogical content knowledge, and combine and formulate that knowledge in written form. Consequently, these writing activities focus on helping students operationalize their disciplinary knowledge in pedagogical contexts and develop their professional literacies (Macken-Horarik et al., 2006).

What is interesting with this category, though, is that the writing-to-become-teachers perspective seems to trump the learning-to-write perspective. We see that while the activities are grounded in disciplinary contexts, they are presented primarily as opportunities to explore concepts, genres and forms of communication that are central to teacher educators of all disciplines. As a result, in line with the previous category, there are only minimal disciplinary differences in the ways the writing is facilitated. We also note that metacommunication about the roles and purposes of writing in disciplinary and professional contexts is missing from these literacy events, thus echoing observations made previously about the implicitness of writing in these activities.

Overlapping perspectives on writing

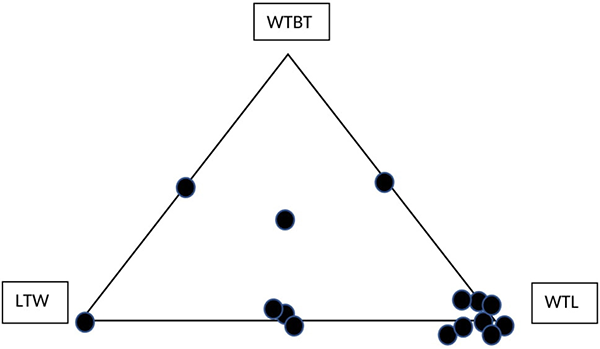

As we mentioned briefly in the analytical approach section, previous literature has suggested that the categories we used to analyze the perspectives on writing are not mutually exclusive, but overlapping (Carter et al., 2007, McLeod, 1987). We also found such an overlap to be the case in our material. We identified six writing activities that include two perspectives, and two that include all three. Example 3, for instance, aims to help students develop content area literacy (writing-to-learn) and explore aspects central to writing in the discipline (learning-to-write). Example 6 appears as a model activity to develop writing tasks for classroom use and includes all three perspectives; it asks students to use writing to access and transform content knowledge (writing-to-learn), to develop a type of disciplinary text (learning-to-write) they will use as teachers (writing-to-become-teachers).

The overlap of perspectives which the categories reflect may be said to illustrate the complex and versatile nature of writing in teacher education. However, it also raises questions about the limitations of these categories for the purposes of empirical analysis. While the categories are useful as shorthand to communicate different perspectives in the abstract, at least in our empirical context, few of the writing activities can be easily said to be one or the other only. Hence, for the purposes of empirical analysis, it might be more useful to think of these categories as a continuum, where perspectives can play larger or smaller roles. Figure 1 illustrates our operationalization of what the overlap of perspectives on writing in our material looks like when placed on a continuum. We see such a continuum as a continuation of previous work that has noted the overlap, and as a starting point for future conversations about how these perspectives serve to limit or enable different understandings of writing. We return to this point in the discussion.

Discussion and concluding remarks

In this study, we set out to explore the in-class writing activities a multidisciplinary group of teacher educators included in their teaching, and the perspectives on writing which these activities may reflect. Our approach and study design necessarily shape our analysis and the conclusions that may be drawn. In particular, our snapshot approach, in which the participants selected the sessions when they would be working with writing, does not allow us to make general conclusions about these teacher educators’ use of in-class writing activities. If we had entered their classrooms at a different point in the semester or followed them over time, we would most likely have gotten to see different writing activities. Nevertheless, by looking across several classrooms, our analysis shows perspectives on writing that might resonate with teacher education contexts similar to the one in our study. As such, our findings contribute to what Flyvbjerg (2006) calls “the collective process of knowledge accumulation” (p. 227) in the field. Our study thus constitutes a starting point for further research. In the following, we will present and discuss three central findings in light of the research question: What perspectives on writing are reflected in the writing activities in these literacy events?

First and foremost, we find that writing-to-learn perspectives on writing dominate across our material. This is evident in the fact that the activities were framed as thinking pieces (Bean, 2011). They provided students with the opportunities to explore course content and disciplinary concepts, and familiarize themselves with professional genres, conventions and practices. As such, writing constituted a cognitive aid in the student’ learning processes, helping them put their thoughts into words, onto paper (cf. Bean, 2011; Emig, 1977; McLeod, 1987). However, we also noted that the thinking and writing was always intertwined with forms of dialogue and interaction, as illustrated by the fact that the students often co-wrote chunks of text, or engaged in reflective activities based on their writing with their peers. This highlights a perception of writing as a social activity (cf. Barton & Hamilton, 2000), and resonates with Wittek et al.’s (2017) observations that in-class writing activities are often social in nature.

In our material, then, writing is commonly used to explore disciplinary content and professional concepts and practices, and less frequently to explore disciplinary writing, at least explicitly. We see that the teacher educators predominantly promote ways of using writing that can be applied across disciplines to help students develop content area literacy (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008) and professional literacies (Macken-Horarik et al., 2006). This suggests that these teacher educators understand writing as a key mediating tool in the students’ development of disciplinary content knowledge. They also seem to perceive it as central in the students’ process towards becoming professional practitioners, an observation which echoes existing research (see, e.g., Neff et al., 2012; Nilssen & Solheim, 2012; Solbrekke & Helstad, 2016).

It should be noted that we did not explore the potential reasons for the focus on learning in most of these writing activities. However, the teacher educators’ participation in the previously mentioned writing seminar, which promoted writing as a central tool for thinking and learning across disciplines, may have shaped the types of writing activities they used in the observations and resulted in the prominence of writing-to-learn activities in our data material.

We also observe that, perhaps due to the cross-disciplinary focus on writing to learn and content learning in these literacy events, the writing is facilitated similarly in the different disciplines. Even in activities which include disciplinary writing, aspects such as genre conventions and discourse are not given particular attention. For instance, in activities where students practiced genres and skills that are relevant to them as student writers in different disciplines in academia (see Examples 3 and 4), the focal point was on content – i.e., what the students wrote – rather than on form or purpose – i.e., how, or why, they wrote. The focus on content learning in these writing activities mirrors findings from Blikstad-Balas et al.’s (2018) study on writing opportunities in lower secondary school. Moreover, we also found that the writing activities were similar in structure and format across the disciplines, as they were generally presented as informal pieces geared to spark the students’ thinking. Thus, in our material, the focus is on writing across disciplines rather than in disciplines.

Considering the focus on writing as a learning tool, it is perhaps not surprising that none of the writing activities in our material focused explicitly on aspects of writing instruction. This may give the impression that the learning-to-write perspective is absent from these teacher educators’ classroom practices; however, we found this not to be the case. Quite a few of the writing activities presented students with the opportunity to explore ways of thinking about, using and carrying out writing in the disciplines and in the teaching profession, even if the students did not produce complete texts. In line with Carter et al. (2007), we argue that such acts or exploration and reflection are central in learning to write in the disciplines and in professional contexts, because they help students learn about “the ways of knowing and doing that define the discipline” or profession (p. 280).

The teacher educators’ use of writing-to-learn activities to explore aspects of disciplinary and professional writing may embody the notion that learning to write can take many forms and occur in a number of contexts, also in activities where writing instruction is not made an explicit focus or where the writing itself does not constitute the main goal of the activity. In this respect, our findings suggest that for these teacher educators, the concept “writing activities” comprised a much broader understanding of writing than what is typically associated with the learning-to-write perspective. It implies a wide and rich – and we think, useful – understanding of writing activities which encompasses writing in a wide range of forms, purposes and contexts. This understanding of writing aligns with Barton and Hamilton’s (2000) broad definition of literacy, and highlights Blikstad-Balas’ (2013) argument that in educational contexts, writing activities often focus on learning rather than writing instruction.

The multiple perspectives on the uses of writing activities described above underscores our second central finding, namely that the perspectives on writing reflected in these activities should not be understood as mutually exclusive categories, but rather as a continuum of overlapping perspectives. The usefulness of conceptualizing the perspectives as a continuum has been noted by others who have examined perspectives on writing in other disciplinary contexts (Carter et al., 2007; McLeod, 1987). As our analysis reveals, the perspectives learning-to-write, writing-to-learn and writing-to-become-teachers rarely occurs in isolation in any particular writing activity. Instead, a writing activity might primarily be a writing-to-learn activity but contain elements of the learning-to-write and/or writing-to-become-teacher perspectives. In short, while the categories in our analysis work well as shorthand to explain different functions of writing, they may be too blunt to capture the complexity of writing as it unfolds in classroom contexts.

While such a proposition must be further explored in future research to assess its applicability in other contexts, it was notable in our material, as illustrated in Figure 1. Indeed, such a continuum might also be pedagogically useful for teacher educators and for students, as an instrument that could be used to spark discussion and to develop awareness of the functions and roles of different types of in-class writing in teacher education classrooms and in schools.

Finally, we see that neither the writing activities themselves, nor the perspectives inherent in them, were explicitly discussed as pedagogical choices. In other words; there was limited metacommunication between the teachers and the students about the writing that occurred in these literacy events. While the teacher educators framed the activities in the teaching context, they only occasionally brought attention to disciplinary aspects of writing or aspects of text production or the pedagogical affordances of writing activities in teaching and learning contexts. In their study from Norwegian lower secondary school, Blikstad-Balas et al. (2018) similarly found that the teachers seldom engaged in meta-talk about issues related to writing in their classes.

Ultimately, one consequence of the limited metacommunication about writing is, as our analysis illustrates, that the writing that takes place in these literacy events becomes implicit. The lack of explicitness may be due to the prominent focus on students’ thinking and content learning in these writing activities, and thus the writing itself is not perceived to be the primary goal of the activity. Nevertheless, we find the lack of metacommunication about writing a bit surprising given that the teacher educators had participated in the writing seminar and volunteered to take part in this study, which could suggest that they had a raised awareness about these issues.

However, we find the limitations in teachers’ metacommunication about writing problematic, as previous research has also stated (Greek & Jonsmoen, 2016; Jonsmoen & Greek, 2012). The lack of explicitness about the writing that takes place is particularly unfortunate when considering the students’ future careers as teachers and the role of writing across educational levels. With this in mind, it is crucial that teacher educators can make the pedagogical rationales behind their use of in-class writing activities explicit to the students, as this may help raise the students’ awareness about writing as a tool in teaching and learning contexts. Such knowledge is central to teachers’ practices on all levels of education. Arneback et al. (2017) also point out that metacommunication about writing is important to students’ development into professional practitioners. Our analysis suggests that there is untapped potential among these teacher educators with respect to explicitly discussing their uses of in-class writing activities with their students.

Through our exploration of the writing activities in these literacy events, we have contributed valuable knowledge about the uses of and perspectives on such activities in teacher education classrooms. Importantly, our study shows that this group of teacher educators perceive in-class writing activities primarily as versatile learning tools, often serving multiple, overlapping purposes. Consequently, the perspectives on writing reflected in these activities are not mutually exclusive, but exist on a continuum – between writing-to-learn, learning-to-write, and writing-to-become-teachers. As such, our study contributes insight into how in-class writing activities can be understood and used in teaching and learning contexts across disciplines and classrooms in teacher education. At the same time, we observed clear limitations regarding in-class metacommunication about the writing that took place, which we find unfortunate considering the importance of writing in students’ academic and professional careers. More research into in-class metacommunication about writing in teacher education classrooms is welcome, as such research could contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the roles and functions of writing in teacher education in general.

References

- Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg. K. (2018). Reflexive methodology. New vistas for qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Arneback, E., Englund, T., & Solbrekke, T. D. (2017). Student teachers’ experiences of academic writing in teacher education – On moving between different disciplines. Education Inquiry, 8(4), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2017.1389226

- Bangert-Drowns, R. L., Hurley, M. M., & Wilkinson, B. (2004). The effects of school-based writing-to-learn interventions on academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 29–58. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001029

- Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (1998). Local literacies: Reading and writing in one community. Routledge.

- Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (2000). Literacy practices. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton, & R. Ivanič (Eds.), Situated literacies. Reading and writing in context (pp. 1–15). Routledge.

- Bean, J. C. (2011). Engaging ideas. The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Blikstad-Balas, M. (2013). Redefining school literacy. Prominent literacy practices across subjects in upper secondary school [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Oslo.

- Blikstad-Balas, M., Roe, A., & Klette, K. (2018). Opportunities to write: An exploration of student writing during language arts lessons in Norwegian lower secondary classrooms. Written Communication, 35(2), 119–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088317751123

- Carter, M., Ferzli, M., & Wiebe, E. N. (2007). Writing to learn by learning to write in the disciplines. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 21(3), 278–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651907300466

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). Routledge.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Deane, M., & O’Neill, P. (2011). Writing in the disciplines: Beyond remediality. In M. Deane & P. O’Neill (Eds.), Writing in the disciplines (pp. 3–13). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Emig, J. (1977). Writing as a mode of learning. College Composition and Communication, 28(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.2307/356095

- Erixon Arreman, I., & Erixon, P.-O. (2017). En gränsöverskridare på väg mot ett professionellt habitus [Cross-bordering on the way towards a professional habitus]. In P.-O. Erixon & O. Josephson (Eds.), Kampen om texten. Examensarbetet i lärarutbildningen (pp. 79–96). Studentlitteratur.

- Erixon, P.-O., & Josephson, O. (Eds.). Kampen om texten. Examensarbetet i lärarutbildningen [Struggling with the text. Exam work in teacher education]. Studentlitteratur.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Gee, J. P. (2015). Social linguistics and literacies. Ideology in discourses. Routledge.

- Gere, A. R., Knutson, A. V., Limlamai, N., McCarty, R., & Wilson, E. (2018). A tale of two prompts: New perspectives on writing-to-learn assignments. The WAC Journal, 29(1), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.37514/wac-j.2018.29.1.07

- Greek, M., & Jonsmoen, K. M. (2016). Hvilken tekstkyndighet har studenter med seg fra videregående skole? [Which text competencies do students acquire in upper secondary education?] Uniped, 39(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1893-8981-2016-03-06

- Helstad, K., Solbrekke, T. D., & Wittek, A. L. (2017). Exploring teaching academic literacy in mathematics in teacher education. Education Inquiry, 8(4), 318–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2017.1389225

- Hume, A. (2009). Promoting higher levels of reflective writing in student journals. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(3), 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360902839859

- Jonsmoen, K. M., & Greek, M. (2012). «Hodet blir tungt – og tomt» – om det å skrive seg til profesjonsutøvelse [“The head grows heavy – and empty” – On writing in professional practice]. Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift, 1, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-2987-2012-01-03

- Klemp, T., Strømman, E., Nilssen, V., & Dons, C. F. (2016). På vei til å bli skrivelærer. Lærerstudenter i dialog mellom teori og praksis [Becoming a writing teacher. Teacher students in dialogue between theory and practice]. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Kvernbekk, T. (2005). Pedagogisk teoridannelse. Insidere, teoriformer og praksis [Developing pedagogical theory. Insiders, types of theory and practice]. Fagbokforlaget.

- Leon, A. (2020). Low-stakes writing as high-impact education practice in MBA classes. Across the Disciplines, 17(3/4), 46–68. https://doi.org/10.37514/ATD-J.2020.17.3.02

- McLeod, S. (1987). Defining writing across the curriculum. WPA: Writing Program Administration, 11(1–2), 19–24.

- Macken-Horarik, M., Devereux, L., Trimingham-Jack, C., & Wilson, K. (2006). Negotiating the territory of tertiary literacies: A case study of teacher education. Linguistics and Education, 17(3), 240–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2006.11.001

- Moon, A., Gere, A. R., & Shultz, G. V. (2018). Writing in the STEM classroom. Faculty conceptions of writing and its role in the undergraduate classroom. Science Education, 102(5), 1007-1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21454

- Mortari, L. (2012). Learning thoughtful reflection in teacher education. Teachers and Teaching, 18(5), 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.709729

- Neff, J., McAuliffe, G. J., Whithaus, C., & Quinlan, N. P. (2012). Low-stakes, reflective writing: Moving students into their professional fields. Currents in Teaching and Learning, 4(2), 18–30. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1073&context=english_fac_pubs

- Nilssen, V., & Solheim, R. (2012). Å forstå kva elevane forstår. Om skriving som bru mellom teori og praksis i lærerutdanninga [Understanding what the students understand. On writing as a bridge between theory and practice in teacher education]. In G. Melby, & S. Matre (Eds.), Å skrive seg inn i læreryrket (pp. 69–87). Akademika forlag.

- Northedge, A. (2003). Rethinking teaching in the context of diversity. Teaching in Higher Education 8(1), 17–32.

- Ofte, I., & Otnes, H. (2022). Collegial conversations about writing instruction in teacher education: Positions, perspectives, and priorities. In R. Solheim, H. Otnes, & M. O. Riis-Johansen, (Eds.). Samtale, samskrive, samhandle. Nye perspektiv på muntlighet og skriftlighet i samspill. Universitetsforlaget.

- Palmquist, M. (2020). A middle way for WAC: Writing to engage. WAC Journal, 31(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.37514/wac-j.2020.31.1.01

- Russell, D. R. (2002). Writing in the academic disciplines. A curricular history (2nd ed.). Southern Illinois University Press.

- Russell, D. R., Lea, M., Parker, J., Street, B., & Donahue, C. (2009). Exploring notions of genre in “academic literacies” and “writing across the curriculum”: Approaches across countries and contexts. In C. Bazerman, A. Bonini, & D. Figueiredo (Eds.), Genre in a changing world (pp. 395–423). Parlor Press.

- Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content- area literacy. Harvard Educational Review 78(1), 40–59. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.78.1.v62444321p602101

- Solbrekke, T. D., & Helstad, K. (2016). Student formation in higher education: Teachers’ approaches matter. Teaching in Higher Education, 21(8), 962–977. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1207624

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language (A. Kazoulin, Ed. & Trans.). MIT Press.

- Wittek, A. L., Askeland, N., & Aamotsbakken, B. (2015). Learning from and about writing: A case study of the learning trajectories of student teachers. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 6, 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2015.02.001

- Wittek, L., Solbrekke, T. D., & Helstad, K. (2017). Med mappen som redskap i kampen om teksten. In P.-O. Erixon & O. Josephson (Eds.), Kampen om texten. Examensarbetet i lärarutbildningen (pp. 97–125). Studentlitteratur.